“Conserving New Mexico’s wildlife for future generations” — this small slogan of the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish (NMDGF) has a large meaning. It speaks to the importance of wildlife in people’s lives, and to the impact that wildlife and nature can have in shaping who we are and the paths that we choose. And it speaks to the importance of conservation so that those that come after us can also enjoy the life-changing experiences of the natural world.

This is not a unique ideology but is rather common ground that hunters, anglers, birders, wildlife photographers and all manner of outdoor enthusiasts share. The concept can also be seen as an heirloom, passed down from generation to generation. Someone probably took the time to introduce each of us to their passion for the outdoors and the importance of conservation and, as we grow as outdoors enthusiasts, we recognize the importance of passing this love of the natural world on to others. And sometimes, we are able to see this ideology play out on a grand scale. That is the story of Mr. Griggs’ pronghorn.

Once found throughout the desert scrub, short-grass prairies and mountain grasslands of New Mexico, westward expansion and unregulated hunting resulted in a rapid decline in pronghorn populations. Extremely low pronghorn population estimates were reported in New Mexico in the early 1900s, with State Game Warden Trinidad C. de Baca reporting 1,700 pronghorn in 1912, and J. Stokley Ligon, a field biologist for NMDGF in the 1920s, stating that pronghorn populations may have declined to 1,200 animals in the previous decade.

Public sentiment started to change, with homesteaders and ranchers beginning to conserve the small bands of antelope remaining on their lands. For greater protection of pronghorn, the state designated vast areas where the unauthorized carrying of guns was prohibited and was upheld by the courts with stiff fines of $25 or more. Pronghorn trapping and translocation procedures were established by NMDGF and transplants of pronghorn occurred in the decades to follow. These efforts resulted in the state’s pronghorn population recovering to 20,000 to 25,000 animals prior to 1950.

Due to these successes, a very limited number of pronghorn hunting licenses began to be issued in the 1930s and 1940s. These highly regulated, buck-only hunts did not occur every year and were only two to three days in length. Hunts were established in areas where the number of bucks far exceeded the number needed for perpetuation of the herd and where sheep-proof fencing prohibited natural herd dispersal. A hunter would have been very lucky to even receive one of these early pronghorn hunting licenses.

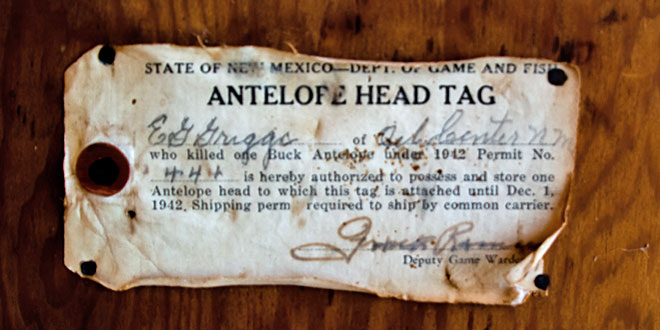

In 1942, Edward J. “Red” Griggs of Oil Center, New Mexico, was one of those lucky hunters. After paying for the $5 permit, Mr. Griggs received Antelope Permit Number 444 along with the instructions that the tag was valid “…from October 9 to October 11, 1942…within the area known as the J.P. White Ranch. Check in and out…east of Roswell.” The letter was signed Elliott Barker, State Game Warden.

Filled with excitement, Mr. Griggs drove down to Roswell on Oct. 8, 1942, with his wife, Evelyn, and their three-year-old son, Michael “Mike” Griggs. They spent the night with their friends, the Elliotts, before they all headed out for the hunt. Mr. Elliott had also received a pronghorn tag for the 1942 season, and Mrs. Elliott was an old hand at pronghorn hunting herself, having drawn tags in both 1940 and 1941.

Before daylight the next morning, Mr. Griggs checked in for the hunt and was assigned to the Sardine Mountain pasture on the White Ranch. That morning he spotted a buck with a double prong on its righthand side, silhouetted against the sky at some distance away. After a long-range shot and the resulting search in tall grass, Mr. Griggs filled his tag with this double-prong buck at 8:30 a.m. It was the largest buck to be harvested in New Mexico that season. Mr. Elliott also harvested a buck at 9:30 a.m. the same morning. They had lunch, loaded the bucks, checked their harvests with Deputy Game Warden Frank Ramsey and were headed back to Roswell by 2 p.m. that afternoon.

While this may seem like a short hunt, its memory has lasted a lifetime for Mike Griggs. Since the hunters had traveled to the ranch by car, both of their wives and Mike were able to accompany them and experience the hunt firsthand. It was young Mike’s first big-game hunting experience. While only three years old at the time, Mike vividly remembers getting up very early for the hunt, the leather-cased guns in the Elliotts’ gun closet and having celebratory fried chicken for lunch after the hunt.

Mr. Griggs had the buck shoulder-mounted, and the taxidermy mount hung in the family home for all of Mike’s childhood. While the Griggs would make several moves over the years, the pronghorn mount was always a fixture of their home. Later in life, when Mike went off to college and later joined the Army, he always knew he had returned home when he saw the double-prong buck.

The love of the outdoors and importance of conservation was firmly ingrained in the heart of young Mike Griggs. He would major in forestry in college and later spent a 32-year career with the state forestry department in Washington. There would be many other big-game hunts that Mike would share with his father and his two brothers through the years, but the memory of that first big-game hunt would always hold a special place in his heart. After his father’s passing in 1991, the mount was relocated to Mike’s home in Bremerton, Washington.

When Mike Griggs turned 80, he started to think about how much the pronghorn buck had influenced his life and began to ponder how he could preserve the legacy of the mount for others to enjoy. He contacted NMDGF and inquired about the possibility of donating the mount. Working with Assistant Director Jim Comins and NMDGF archeologist and historian Jack Young, an agreement was reached. Since the buck had been harvested near Roswell, it seemed only fitting that the mount be displayed in the Roswell NMDGF office, newly built and relocated in 2019.

In September 2021, at age 82, Mike and his wife drove the mount from their home in Washington to the NMDGF office in Santa Fe. Driving over 1,500 miles one way, the Griggs stopped to visit family and friends along the way. One such stop occurred in Wyoming, at a ceremony where one of Mike’s younger brothers, Dr. Kenneth Griggs, was inducted into the Wyoming Cowboy Hall of Fame. Walking out to the car with Mike, his brother said that he needed to see the buck one more time. Obviously, the double-prong buck had a major impact on all three of Mr. Griggs’ sons.

Upon arriving in Santa Fe, Mike Griggs presented the mount to Jack Young, telling the story of the buck and its influence on his life. Accompanying the mount were several photographs of the hunt as well as the original tag signed by Deputy Game Warden Frank Ramsey still tacked to the back of the mount. As Mr. Mike Griggs walked out of the Santa Fe office, and later drove back to Washington, I wonder if he thought about the young aspiring hunters, who will gaze upon the double-prong buck with wonder, they themselves the recipients of the heirloom of conservation.

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations