The following is just a taste of our work with invertebrate SGCN. Invertebrates are creatures that lack (“in-”) backbones (“vertebra”).

The Texas hornshell is one of the few river mussels that are native to New Mexico. Although “spineless,” this mussel has proven robust in its fight to survive. Read on to discover the important part it plays in our biodiversity!

*

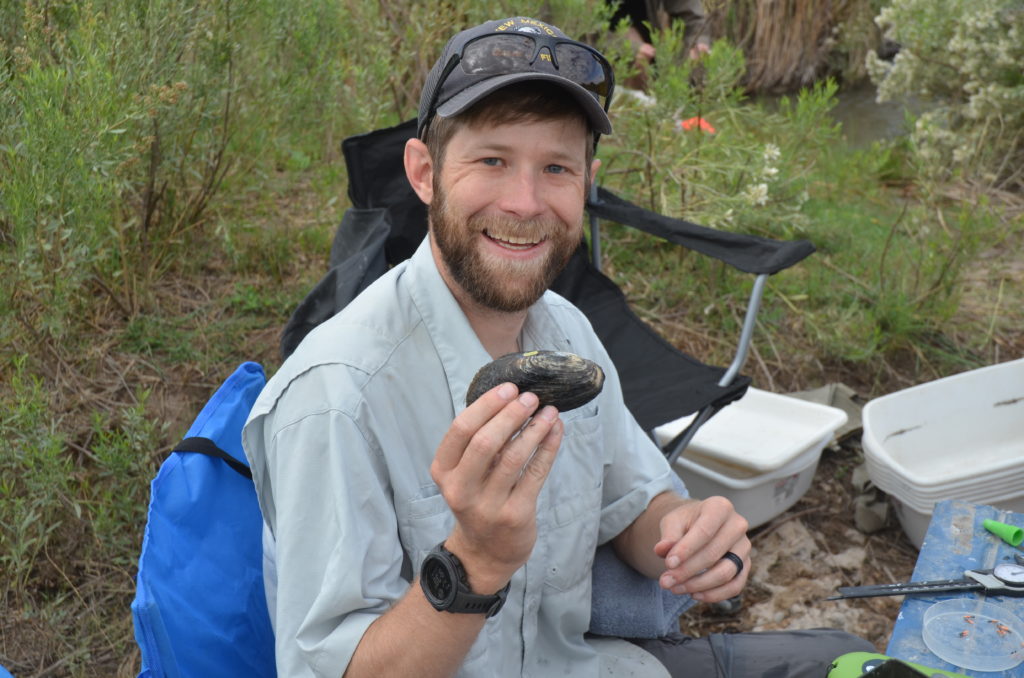

It’s a gray, crisp morning in Southern New Mexico. The back of a wetsuit and goggles hover over the muddy bed of the Black River. The back turns into a young man when he splashes to the surface and sucks in the breeze. Smiling, he raises a shining treasure for all to see.

This isn’t a typical treasure hunter: Nathan Thompson is one of our Aquatic Biologists. And he doesn’t hunt typical treasure: rather than specks of silver or an arrowhead, he grasps a hinged set of black-ridged slopes containing a Texas hornshell.

The Texas hornshell (Popenaias popeii) is a species of freshwater mussel, an aquatic bivalve mollusk in the river mussel family (Unionidae). It’s one of three river mussels endemic to rivers that flow through Mexico, Texas and New Mexico.

After climbing back out of the Black River, Thompson excitedly recounts how we’ve worked with Miami University (in Ohio, not the University of Miami in Florida) to collect data on the Texas hornshell for over 20 years. But his smile starts to fade as he explains this mussel’s status: it is critically endangered.

Its population has been reduced to just 15% of its historical range, currently inhabiting 120 miles of the Rio Grande and a little more than 8 miles of the Black River. Given its importance to our biodiversity, the Texas hornshell’s population size, recruitment, individual growth and survival have been carefully tracked and managed through myriad mark-and-recapture projects like the one Thompson’s currently engaged in.

“These mussels might look like rocks, but don’t be fooled,” Thompson explains. As he holds the invertebrate up to the somber sky, his smile returns. “Freshwater mussels are truly amazing little creatures. They require fish to complete their life cycle. As larvae, the glochidia—sorry, baby mussels—attach themselves to the skin, fins or gills of their hosts.”

Thompson carefully lowers the mussel, cupping his treasure with both hands. “Some mussels are quite particular about host species,” he explains. “Others are generalists. Here in New Mexico, the Texas hornshell prefers a few fish hosts: the gray redhorse, red shiner and blue sucker. Others just host on occasion! Some of these fish are also in need of conservation, which is creating even more challenges for our hornshell.”

As he wades back to the other scientists grouped on shore, Thompson waves victoriously. After a deep breath, he continues to extol his favorite species’s breeding tactics the way a proud father brags about his son: “Some mussels create elaborate lures with their mantel tissue to draw unsuspecting fish into range of their glochidia. These lures will often mimic a small fish the desired host likes to eat. Some, like our hornshell, deploy a mucus net loaded with glochidia. When the fish swim through, they get parasitized.”

Thompson holds the hornshell in one hand and mimics a fish with the other, wriggling his fingers to demonstrate the parasitizing process. “Amazing, right?” He laughs and adds, “This phase of life lasts for only a few weeks, depending on species and water temperatures. Fish also give the mostly sedentary mussel babies a ride upstream, helping to disperse them. The glochidia fall off the fish host then and start a new life as a juvenile mussel on the bottom of the river.”

Thompson is now surrounded by our staff and biologists from MU. Thompson once again clarifies they are not from UM as he carefully puts the hornshell in a container to be tagged.

He’s happy to collect and tag these mussels for a living. He’s also thrilled to be helped by colleagues as enthusiastic as he is about wildlife conservation.

They’re all searching for mussels in the Black River by hand, a slow and arduous effort. The bends where the hornshell lie are often too muddy to see through, so feeling through the riverbed is the only way to find them.

Thompson’s goal is to streamline these searches. “You know, mussels provide important ecosystem services to the rivers and streams they occupy. They stabilize substrate like gravel on the top of a mud puddle.”

But Texas hornshell are vulnerable to being covered by such substrate or scoured out during floods. They occupy undercut banks and ledges where they are more protected from sandy flows. “So mussel beds reduce turbidity of water with their physical presence,” he says.

“Because of their importance to the ecosystem, mussels are good indicators of water quality. Texas hornshell are intolerant of highly turbid and polluted rivers, so a healthy population can indicate a healthy river.”

“They also filter feed organics out of the water column,” he continues, “improving clarity. These services provide trickle down effects for the algae and aquatic plants that need light penetration to photosynthesize, which, in turn, provides habitat and food for fish and invertebrates.” Blinking for a moment, he adds that this species can be summed up as our rivers’s natural filters.

Thompson retrieves the hornshell once marked and returns it to the bed where it was found. As he dries his hands, he becomes serious again. “The hornshell is flow-obligate,” he begins, “meaning it can’t live in stagnant ponds or low-flow environments. If the river is at low volume as well, the temperatures could rise and become deadly for the mussels. Our droughts could become a big problem for the species.”

Until the ashen sky goes out, Thompson’s team will work diligently to tag, measure and record all the hornshells they find. Then they’ll hurry the hornshells back to their beds and find the next ones.

Thompson watches fondly as his treasure disappears into the mud, dancing back into the shadow of the stream. While the Texas hornshell continues its battle for survival, Thompson and his team will continue our larger war to save our SGCN.

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations