What is a food web? What kind of organisms are at the base of a food chain? How do decomposers fit in? What does the food chain of the gray vireo look like? What kind of management actions could be taken to improve the gray vireo’s status in New Mexico? These are all questions that the Asombro Institute for Science Education (Asombro) in Las Cruces is working with students in southern New Mexico to answer.

Asombro, using funds from the Share with Wildlife program, has developed a new series of lessons for what the program calls “Science Intern modules” focused on Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) in Doña Ana County. They are placing particular emphasis on the gray vireo, a species for which the Department of Game and Fish developed a recovery plan in 2007. For these modules, Asombro staff teach four lessons to fifth grade students and then those students turn around and teach three hands-on activities to younger students at their school. Having the older students turn around and teach younger students is an excellent way to incorporate leadership skills into the education experience that Asombro is providing. It also really tests what the students have learned; there is no better way to see what you really know about a subject than by trying to teach someone else about it.

All told, roughly 600 students were reached just with these SGCN focused activities in the 2018-2019 school year. Many more can experience the new SGCN module in future years. Asombro has other science-oriented lessons that it developed starting in 2014 and delivers to even more students each year. These lessons deal with topics including states and properties of matter. All of the lessons are aligned with the “New Mexico STEM Ready!” science standards.

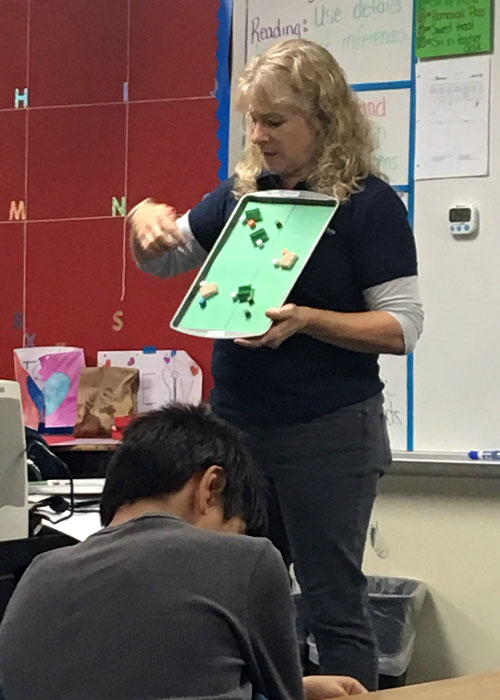

The SGCN focused module, supported with Share with Wildlife funds, starts students off building a food web for the Chihuahuan Desert and learning about species found in playa habitats. They get to observe live tadpole shrimp and learn about other species that live in the desert and near playas. They also work as a group to see connections between organisms in a food web using yarn passed between students representing producers, consumers and decomposers.

Students then dive deeper into food webs by learning about how matter gets transferred between organisms that are in a given food web and how plants convert carbon dioxide into plant tissues. They simulate matter transfer among organisms by passing poms between students representing different animals in the Chihuahuan Desert. They then simulate carbon dioxide uptake from the air by plants using beads and measure carbon dioxide levels over time in the vicinity of photosynthesizing leaves. They finish by learning about decomposers, including viewing some under a microscope.

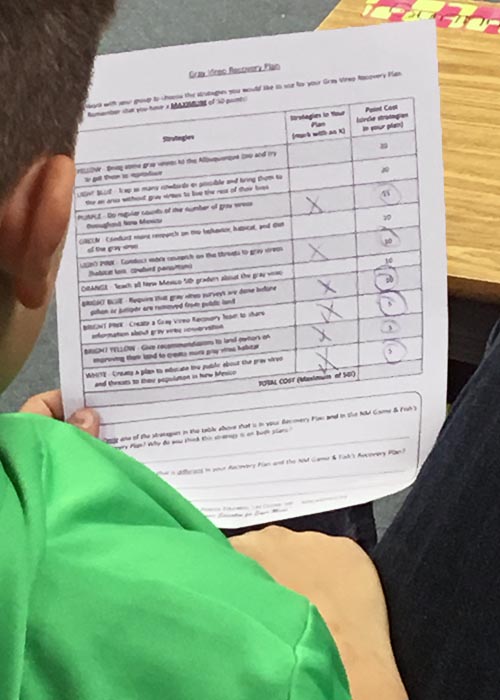

Students proceed to focus in on one species (the gray vireo) and learn about its place in the Chihuahuan Desert food web, natural history and actions that can be taken to conserve it. This includes learning about how cowbirds can parasitize gray vireo nests and the habitat types that vireos use. The students simulate surveying for gray vireos using a point count method. They finally develop their own recovery plan, during which they have to weigh the benefits of various actions against the costs of implementing those actions.

The fifth grade students finally prepare to teach younger students. They give 15 minute presentations to multiple sets of younger students. The younger students learn about food webs, playas and tadpole shrimp and decomposers.

Virginia ‘Ginny’ Seamster, Ph.D., is the BISON-M/Share with Wildlife Coordinator with the Ecological and Environmental Planning Division of the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish.

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations