White-nosed coatis heading north or just heading home?

In early April, game wardens in Albuquerque received an unusual call: a white-nosed coati—also known as a coatimundi—was captured by a local pest control company in the village of Corrales situated on the Rio Grande Bosque in Sandoval County.

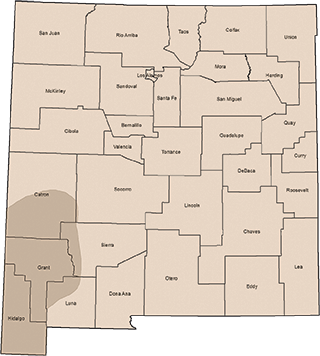

Corrales—or, really, anywhere far north and east of New Mexico’s southwestern region—is well beyond the usual range of the coati. It is uncommon to spot a coati outside of the Gila River area or the “boot heel” of New Mexico, leaving game wardens and biologists wondering if these animals, which are similar in appearance to and can easily be confused with raccoons and ringtails, are finding suitable pockets of habitat further north.

“With their long tails raised in the air, they look like monkeys to some,” said Jim Stuart, endangered nongame mammal biologist at the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, who said he has received calls from people who spotted coatis and describe what sounds like a monkey. “This was the farthest north on record that a coati has ever been captured or spotted. The thought was that this was limited to the southwest part of the state. Perhaps they are rebounding and moving back into areas that they occupied not that long ago.”

Around the turn of the century, there were records of coati found in the Gila Mountain and Black Range; more recently they have been showing up in the Rio Grande Valley in southern New Mexico, in the towns of Hatch, Las Cruces and San Acacia.

He notes that most of these were all individual animals. Where the species has established populations, they are often seen in large groups, called troops.

Coatis have recently been reported on the Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge. There also have been a couple of records from San Acacia in Socorro County, raising the suspicion that maybe these reports from Bosque del Apache and La Joya Wildlife Management Area are not too far-fetched, Stuart said.

But without the scientific specimens, it’s hard to say that for sure, he cautioned. The department has received reports of coati sightings but it’s hard to determine a true range using only word-of-mouth reports without photographic evidence.

Jennifer Frey, a professor in the department of Fish, Wildlife and Conservation Ecology at New Mexico State University, cautions that people shouldn’t leap to the assumption that an unusual sighting of a coati necessarily means a range expansion, especially when considering factors such as climate change and environmental factors that are changing through land use practices.

Frey, who has conducted research on the geographic range of the coati and is currently writing a chapter on coatis for a book about carnivores in New Mexico, noted that one of the challenges is that New Mexico was colonized by Spain in 1598, making it the first place to be permanently colonized by Europeans in the United States (Jamestown, the first English settlement on the East Coast was in 1607). This exceptionally long period of settlement has resulted in altered environments due to human land uses and altered wildlife communities.

“Our historical record is based on a landscape that already changed,” she noted. “We don’t have information about conditions before New Mexico was influenced by Europeans. What people may see as a range expansion may be the species returning to a historical range that had been impacted by humans. Just because we’re seeing something in an unusual place today doesn’t mean it’s unusual for the species.”

In fact, she said, coatis may have been more abundant in the past. One hypothesis is that extensive predator control activities that occurred in the 20th century could have decreased the abundance and distribution of coatis in the state. “It seems as though there has been a range expansion when in fact it is probably representing what their natural distribution is,” Frey said.

The coati captured in April was not the first one found in the Albuquerque area, according to Frey, who added that its presence doesn’t point to a resident coati population in the Albuquerque area.

“Keep in mind, people don’t blink an eye if a bird is blown off course, but when it’s a mammal people react to it in a different way,” Frey said. “Male coatis can spend much of the year away from the bands of females and young, during which time they may wander long distances. So, occasional occurrences of solitary males well beyond their normal range are not surprising.”

Of course, another possibility is that the Corrales animal was an escaped captive, although keeping coatis as pets in New Mexico is not legal.

The following day, the coati was transported to the Red Rock Wildlife Management Area about 26 miles north

of Lordsburg, back home to its familiar habitat, where coatis typically reside.

About coatis

Coatis are part of the Procyonidae family, the same as raccoons and ringtails. Coatis are omnivores and forage for plant, fruit, arthropods and insects. In fact, when the department recently baited for wild turkeys, a pack of coatis showed up to eat the bait. The range of coati extends as far south as South America and currently, at least as far north as southwestern New Mexico and central Arizona.

To learn more about coatis, visit: http://bison-m.org/booklet.aspx?id=050165

If you spot a coati

– Take a photo and record the location information. You can call the Department of Game and Fish public information number at 1-888-248-6866 to report the possible sighting.

– Do not try to collect it. It is a protected furbearer that isn’t trapped. It has full legal protection under New Mexico law.

– Remember: It generally is illegal for New Mexico residents to have a coati as a pet, even if it was acquired outside of New Mexico. While there are some captive coatis in the state, you have to have a special permit to keep one.

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations