Restoration of Gila trout opens door for anglers

It’s been five years since two massive wildfires roared through the Gila Wilderness and surrounding national forest, destroying years of painstaking native trout restoration work.

“I was interviewing for this job while everything was burning up,” said Jill Wick, Gila trout biologist for the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish. “It was pretty devastating to see how much damage had been done.”

The Whitewater-Baldy Fire in 2012 charred almost 300,000 acres and wiped out six populations of Gila trout. The following year’s Silver Fire scorched an estimated 138,000 more acres and killed off two more populations.

Many fish died from the poisonous effects of ash washed into the streams following the fires. Unchecked rain runoff swept mud and debris into the streams, wiping out habitat and smothering any remaining fish and the insects upon which they fed.

Altogether the fires destroyed 8 of 17 Gila trout populations and 47 miles of habitat. It was a significant setback to Gila trout restoration

But Wick and her partners at the U.S. Forest Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have since rallied and made enough gains that angling opportunities for the elusive trout have been expanded.

“The last five years have been challenging, but we’ve been able to restore several of those lost Gila trout populations and even added a couple new ones,” Wick said.

“A big part of the reason we have been able to rebound so quickly is because of the partnerships, planning and work that’s already been done,” Wick said. “And the Mora National Fish Hatchery has been crucial to our ability to return fish to streams so quickly.”

Gila trout have been restored to White Creek, Black Canyon and Langstroth Creek. Two others, Willow and Mineral creeks, were cleared of non-native game fish by the fire and have been restocked with Gila trout.

Five other streams containing Gila trout that were killed off by the fires are in remote, rugged areas where it will take years of natural processes to improve stream conditions to the point where they can be restored. Four of those also will require the construction of barriers.

Barriers, such as the one recently completed on Willow Creek, prevent non-native fish from migrating upstream into Gila trout habitat. Non-native fish compete with Gila trout for food and shelter, prey upon their young and threaten their bloodline through cross-breeding.

At one point during the 1970s, Gila trout could only be found in the headwaters of five streams within the Gila region and it was on the federal endangered species list primarily because of competition with non-native fish and hybridization.

Fish and Wildlife downgraded the Gila trout’s status to threatened in 2006 based upon more than 20 years of intense restoration efforts by partnership agencies. Limited angling for the prized trout was then allowed under the new listing.

Many of those previous projects included the installation of fish barriers and instream habitat improvements, along with the removal of non-native fish and the restocking of pure-strain Gila trout.

The fires then roared through and wiped out much of the restoration work.

“Now, five years later, we’re back to about where we were before the fires,” Wick said.

Recovery efforts have restored Gila trout to pre-fire conditions of 17 populations and about 81 miles of habitat.

The department’s long-term goal is to restore Gila trout to a self-sustainable point where repeated human intervention won’t be necessary to ensure its survival.

The plan is to restore 168 miles of habitat with 39 distinct populations of Gila trout. Currently, these trout occupy approximately 12 miles of historical habitat in four populations in Arizona and 69 miles of historical habitat and 16 populations in New Mexico.

“Having more trout spread out over a wider area can help mitigate the effects of these kinds of catastrophic wildfires,” said Kirk Patten, assistant chief of fisheries for Game and Fish.

The next phase is to restore Gila trout to a 24-mile stretch of Whitewater Creek.

Most non-game fish in the creek were killed by the fire, presenting biologists with an opportunity to restore Gila trout to the stream. They plan to return this fall and the spring of 2018 to finish clearing the creek of any remaining non-native fish.

The stream will be treated with rotenone, a naturally occurring substance derived from the roots of tropical plants that affects only gill-breathing animals. When used according to the product label, rotenone poses no threat to humans. It is effective at killing fish, degrades rapidly and can be neutralized immediately below the treatment area.

Gila trout, speckled dace, desert suckers and Sonora suckers will be stocked in the creek once it is free of any remaining non-native fish and insect life has recovered.

Wick said a barrier won’t be needed on Whitewater Creek because several natural waterfalls provide deterrents to upstream migration of any non-native fish.

The estimated $200,000 project is funded primarily through excise taxes collected on the sale of fishing tackle and motorboat fuel, with the remainder of the cost picked up by the department.

The project is expected to be completed in three years and will add about 14 percent more Gila trout habitat toward the restoration goal.

In the process, the work will provide anglers with a unique opportunity to fish for native trout in more accessible areas.

Gila Trout Swim Mineral Creek:

Devastating fire cleared path for trout’s return

By Craig Springer, U.S. Fish and Wildlife

Wear and tear on boot soles and a helicopter were prerequisites to getting Gila trout safely placed in the remote headwaters of Mineral Creek inside the Gila National Forest of southwestern New Mexico.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, working with the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish and the U.S. Forest Service, released two age classes of Gila trout ranging up to a foot long into the creek in November.

The rare yellow trout were spawned, hatched and raised at the service’s Mora National Fish Hatchery.

The 1,033 trout were hauled eight hours to meet a helicopter at the Gila National Forest Glenwood Ranger Station. The aircraft made multiple flights carrying an aerated tank full of Gila trout.

Biologists from the three agencies hiked several miles to meet the trout and place them in the cool, shaded runs and pools of Mineral Creek, a tributary to the San Francisco River near Alma, N.M.

Above, Photo 1: Andy Dean, Gila trout biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, places a bucket into Mineral Creek and watches as Gila trout reared at the Mora National Fish Hatchery, begin to explore their new habitat. Photo by Craig Springer, USFWS. Photo 2: Accessing Mineral Creek is a difficult task, so biologists hiked into two areas along the creek and Gila trout, held in an oxygenated tank, were helicoptered in to the release sites. Personnel on the ground would release the tanks from the end of a long cable. Photos by Craig Springer, USFWS.

Streams in this watershed harbor one of five known relict genetic lineages of Gila trout, which live only in New Mexico and Arizona.

“This release is a large step forward in conserving Gila trout,” said Andy Dean, lead Gila trout biologist with the service’s New Mexico Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office in Albuquerque.

“Not only does this add a population within the San Francisco River drainage, it helps establish Gila trout populations across a larger geographical area.”

Mineral Creek came to the attention of biologists as a candidate stream to receive Gila trout following the massive Whitewater-Baldy Fire of 2012.

“Destructive as it was, the forest fire made Mineral Creek suitable for Gila trout,” Dean said. “The fire burned in the headlands of the stream and summer rains washed a slurry of ash and debris down its course.”

The resulting ash flow created a toxic aquatic environment for unwanted non-native species, opening the door to stocking the native trout when conditions improved.

“Though the mountain slopes and streamside vegetation are not fully stabilized post-fire, sufficient habitat exists to harbor Gila trout in Mineral Creek,” Dean said.

Mineral Creek Canyon is certainly among the more remote and more difficult Gila trout habitats to reach, but it’s not the only stream to receive them. Last fall, another 8,621 Gila trout were placed in other waters to advance the species’ recovery and entice anglers to go after native trout in native habitats of southwest New Mexico.

Willow, Gilita and Sapillo creeks and West Fork Gila River were recipients of the fish. Unlike the hike into Mineral Creek, these waters are readily accessible.

Gila trout lie in dark water behind boulders and in the scour pools beneath log jams, waiting for bugs or for what anglers may throw their way.

Fishing regulations are available on the Game and Fish website, wildlife.state.nm.us.

Fishing regulations are available on the Game and Fish website, wildlife.state.nm.us.

The Gila trout, protected under the Endangered Species Act, was listed as endangered in 1973 but, through conservation, was downlisted to threatened in 2006.

Craig Springer has worked for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for 24 years. He published a piece in New Mexico Wildlife in 1995, titled “Fish in the Desert,” a story about the rare White Sands pupfish.

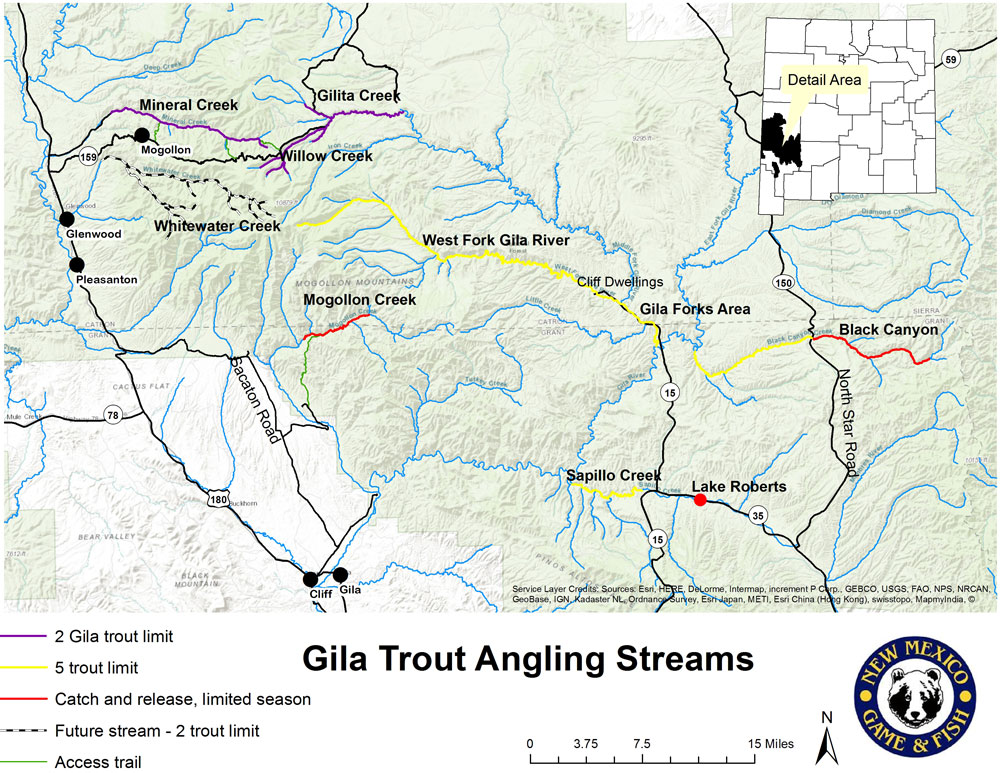

Where to go for Gila trout

By Jill Wick, Gila trout biologist for New Department of Game and Fish

Mogollon Creek from the waterfall to Trail Canyon is open to angling for Gila trout from July 1-Oct. 31. Only catch-and-release angling with single, barbless artificial fly or lure is allowed. To get to Mogollon Creek, take U.S. 180 west from Silver City to the town of Cliff. At Cliff, turn right onto N.M. 211/293 and proceed three miles to Sacaton Road and turn left. Follow for about eight miles to the intersection of 916 Ranch Road, take a right and head north for another 6.5 miles to the 74 Mountain trailhead and parking area. Follow trail 153 about seven miles to the creek.

Willow Creek is open to anglers year-round and has a two-trout bag limit. Approximately 3,000, 5-inch Gila trout were stocked in November. To get to Willow Creek, head south from Reserve on N.M. 435/Forest Road 180 approximately 34 miles to an intersection marked by a sign for Willow Creek and Snow Lake and turn right. After about two miles, arrive at a Y intersection. Turn right and follow about three miles to Willow Creek Campground. Anglers can fish the river on the way to or at the campground or continue upstream by following Willow Creek Ranch Road through a small section of private property. Make sure to close the gate and park at the road’s end. Fishing is possible upstream for about two miles to the headwaters. Alternatively, from U.S. 180 just north of Glenwood, take N.M. 159, known as Bursam Road, east to the Willow Creek Campground. Be advised this road is steep, winding and narrow and is closed during winter.

Black Canyon above the fish barrier is open to catch-and-release angling from July 1-Oct. 31 with single, barbless artificial fly or lure. Trout populations here were severely impacted by the 2013 Silver Fire and subsequent flooding, but the trout population and habitat is beginning to rebound. Over 3,500 Gila trout were stocked in September 2015 and an additional 1,015 in March 2016. To get to Black Canyon, take U.S. 180 east out of Silver City for about eight miles to N.M. 152, turn left and follow for 15 miles. At N.M. 35, turn left and proceed for 15 miles and turn right onto Forest Road 150, known as North Star Road. Follow for 20 miles to the Black Canyon Campground and the large concrete fish barrier. Anglers can fish here for about a mile to a private property boundary. Anglers can access the stream above the private property by following Forest Road 150 north for another 1.5 miles to a parking area and trailhead found on the right at a sharp curve in the road at the top of the mesa. Follow a steep trail for about three miles to Black Canyon.

Mora National Fish Hatchery Gila trout are stocked regularly in six other streams and occasionally in Lake Roberts. The stocked trout are excess fish from the hatchery. The department is planning to raise its own stock of Gila trout at its Glenwood Fish Hatchery to supplement stocking.

West Fork Gila River between Pine Flats and Ring Canyon has a healthy population of Gila, rainbow and brown trout. It was last stocked with 1,200, 4-inch Gila trout in November 2014. Regular bag limits apply. To get to the West Fork of the Gila River, follow the 151 West Fork Trail from the trailhead at the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. Hike about seven miles to Ring Canyon to access dozens of miles of prime, backcountry fishing.

Gilita Creek has been stocked annually for the past three years, most recently in December 2016 with 1,000, 5-inch Gila trout. There is a two trout per day bag limit. To get to Gilita Creek, follow the Willow Creek directions and hike downstream to the confluence of Gilita Creek.

Above, Photo 1: The Whitewater-Baldy Fire of 2012 didn’t directly impact fish in Mineral Creek, but the subsequent ash flows during the monsoonal rains created a toxic environment in the waterway, smothering the stream and killing aquatic life. It took four years before the water conditions were considered suitable for the reintroduction of Gila trout. USFWS photo by Brett Billings. Photo 2: Lake Roberts likely is home to the next state-record Gila trout. NMDGF photo by Dan Williams. Photo 3: The West Fork of the Gila River offers miles of wilderness fishing. NMDGF photo by Dan Williams.

Gila River Forks area was stocked with 2,300, 5-inch Gila trout in November and 2,300, 6-inch Gila trout in January. Regular bag limits apply. To get to Gila River Forks area, follow N.M. 15 between Grapevine Campground and the Gila Cliff Dwellings. Public access points include Grapevine, Forks and Scorpion campgrounds, bridge crossings, the Heartbar Wildlife Management Area, TJ Corral and the Cliff Dwellings National Monument parking area.

Black Canyon below the fish barrier was stocked with 200 Gila trout in March 2016. Recent surveys found plenty of Gila trout in the river below the barrier. Regular bag limits apply. To get to Black Canyon, follow the directions for Black Canyon above the fish barrier and fish downstream of the barrier for several miles.

Sapillo Creek was stocked with 2,300, 5-inch Gila trout in November and 2,000 in January. Regular bag limits apply. The trail to Sapillo Creek is near the intersection of N.M. 15 and N.M. 35. Park in the area at the intersection. Do not park on private property. Walk south down N.M. 15 to an unmarked trail found just before the arroyo crossing and hike downstream about a mile to a ranch gate. Fishing begins there and extends several miles.

Mineral Creek was stocked for the first time in May 2016 with 320, 8-inch Gila trout and again in November 2016 with 530, 12-inch and 500, 5-inch Gila trout. To get to Mineral Creek, hike in on either Log Canyon Trail 808 or South Fork Mineral Creek Trail 798. Both trails are about two miles one way and can be accessed from N.M. 159, known as Bursam Road. Other forest trails can be used to reach various portions of the creek. Consult a reputable map, such as U.S. Forest Service or Bureau of Land Management, for directions.

Lake Roberts was stocked with 5,150, 5-inch Gila trout in January 2016 and 320, 20-inch Gila trout in June. The state record for Gila trout is 20 inches, 4 pounds, 8 ounces. Despite the stocking of numerous record-breaking fish in Lake Roberts, none have been reported caught. Lake Roberts is located on N.M. 35 approximately 19 miles northwest of Mimbres.

Whitewater Creek can be accessed from the Catwalk National Recreation Trail parking area off U.S. 180 near Glenwood upstream 24 miles to the creek’s headwaters and all of its tributaries. The creek will be stocked in the near future upon completion of a project.

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations