A slice of the Great Plains passes through eastern New Mexico, crosses the town of Raton a few miles south of Colorado, then bows west to Las Vegas. Where the elevation begins increasing at the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, the edge of the Plains draws back and follows the Pecos River Valley; a driver heading south through the seemingly arid prairie on U.S. 285 would pass through Roswell, Artesia and Carlsbad, then follow the landscape across the state border into Texas.

During New Mexico’s monsoon season, which runs from July through September, hundreds of shallow, dry depressions in the earth fill with rainwater and runoff from surrounding uplands, revealing ephemeral wetlands that provide habitat for migrating birds and other wildlife. Some dry up within days, while others contain water for weeks or months.

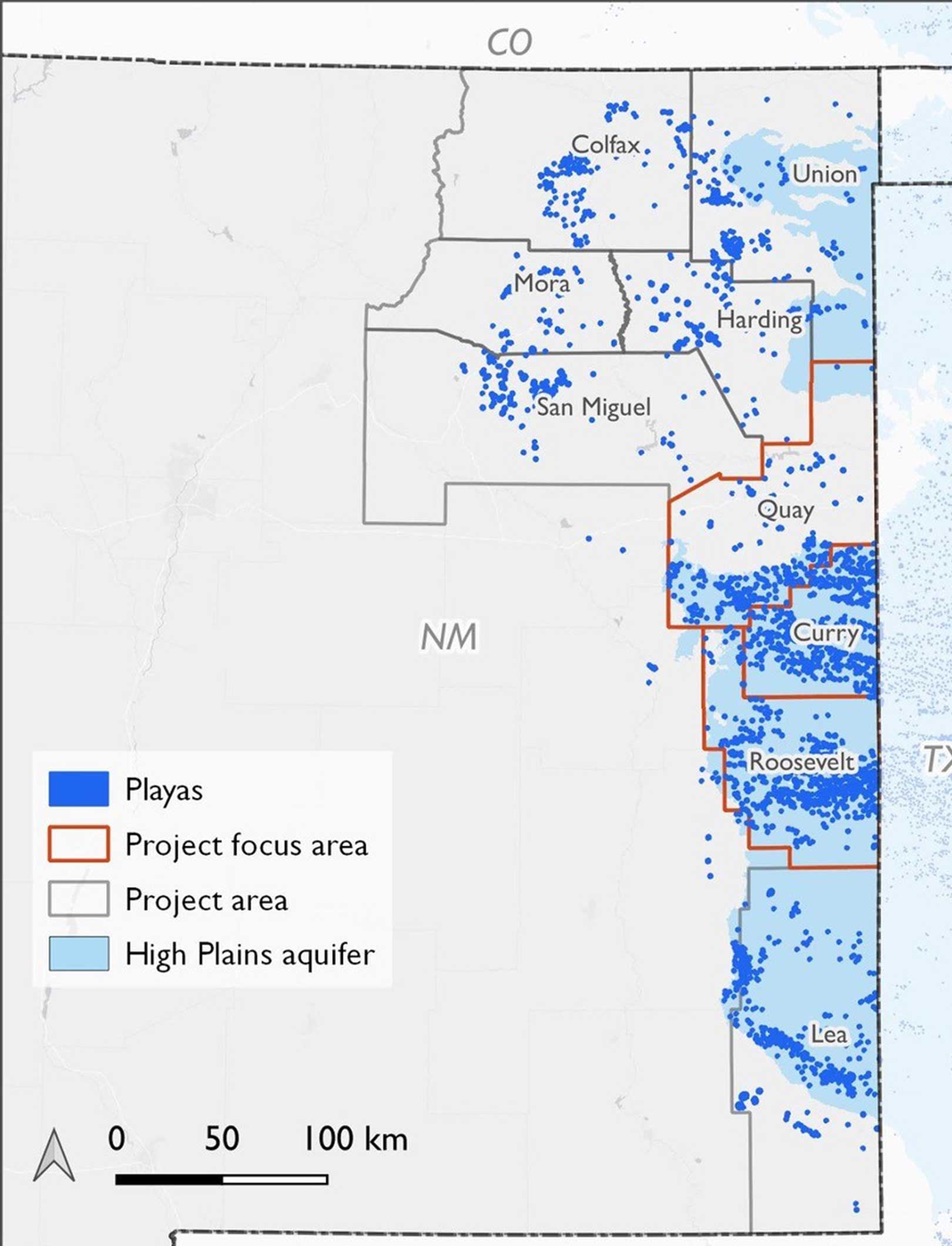

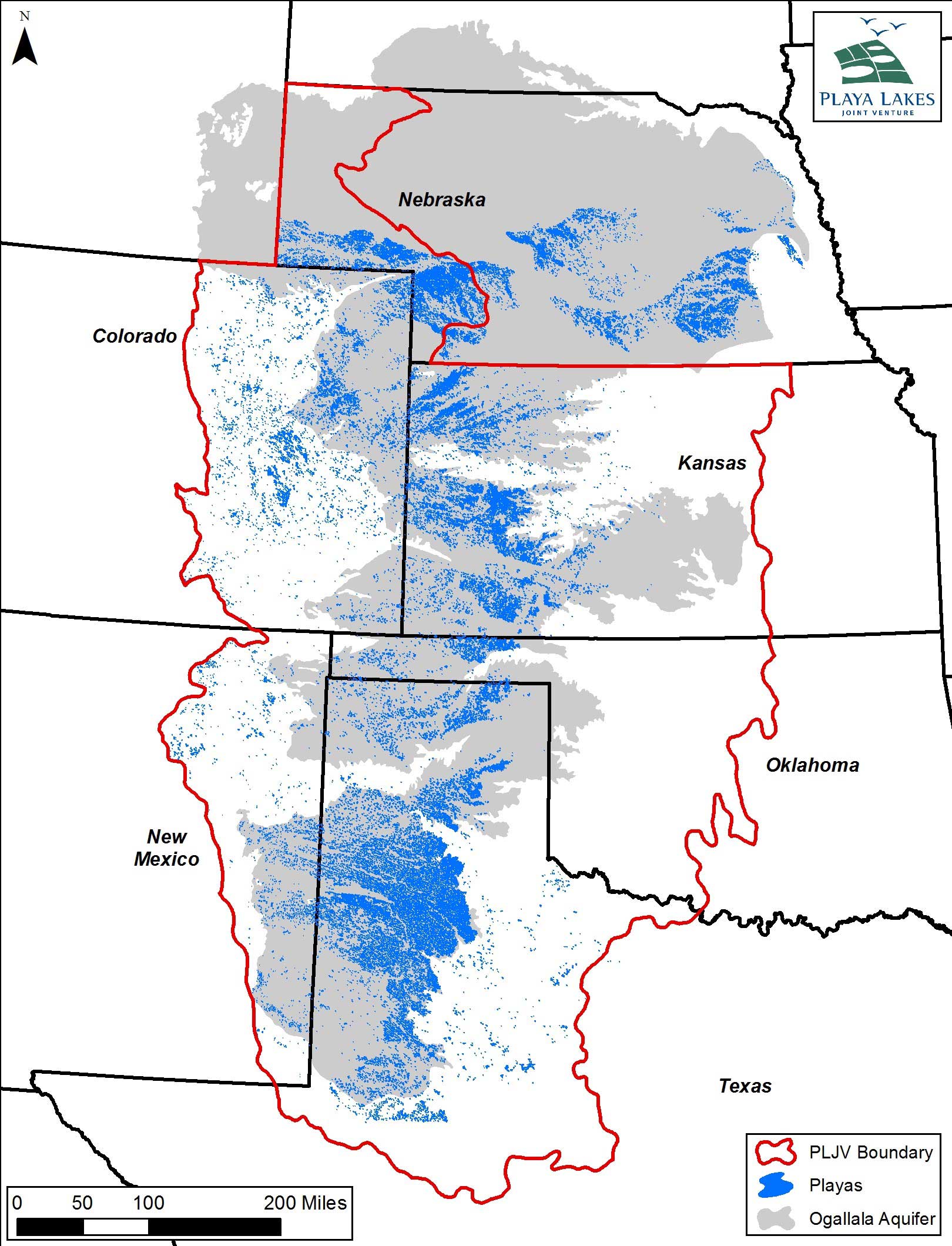

There are more than 80,000 of these basins, or playas, scattered across the western Great Plains, with most of them overlaying the Ogallala aquifer. Playas are a primary source of recharge and contribute up to 95 percent of the water flowing to the aquifer and also improve the quality of that water.

To biologists, playas are so critical to the ecosystem that earlier this year, the Department of Game and Fish partnered with Playa Lakes Joint Venture (PLJV) to establish nearly $1 million in funding, including a substantial grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, dedicated to restoring playas in New Mexico.

Through the program, which covers 100 percent of the restoration costs, private landowners can receive financial and technical assistance to restore the hydrological function of and modify water flow to their playas. The one-time reimbursement payment for the restoration costs is administered through PLJV and Central Curry Soil and Water Conservation District. As part of the program, landowners agree that the playa will not be farmed for 20 years.

“Playas are a primary source of groundwater recharge and centers of biological diversity in the shortgrass prairie,” said Christopher Rustay, conservation delivery leader with PLJV, who oversees playa conservation work in New Mexico and conducts site visits with landowners. “But as these wetlands become degraded, they lose the ability to recharge the aquifer and support plant and wildlife diversity.”

Since February, about 200 acres of playas and surrounding grassland are in the process of being restored, with agreements being developed for an additional 200 acres in southeastern New Mexico, Rustay said.

Elise Goldstein, assistant chief of the Wildlife Management Division with the Department who also serves on the management board of PLJV, said playas are an incredibly important ecological feature that many folks know very little about.

“They have a pivotal role in recharging the aquifer, and since they are a temporary source of water in the arid grasslands, they are critical for wildlife,” she said.

It is the “incredible value” that playas provide to wildlife driving the Department’s commitment to this restoration partnership with PLJV, said Goldstein. The Department brought 75 percent of the total funding— $750,000— to the table, with PLJV providing the remaining $250,000 in nonfederal grants. The Department’s contribution comes from the Pitman-Robertson Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act explained Goldstein.

“There was an opportunity to bring $750,000 in Pitman-Robertson dollars to make the project substantially larger in scope and very meaningful to wildlife conservation,” she said.

***

Known by a few different names—mud holes, buffalo wallows and lagoons, to name a few—the vast majority of playas are found mostly on the Great Plains in seven states: New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado and Wyoming. They often occur in clusters, as they do in the southeastern quadrant of New Mexico and the Texas Panhandle.

PLJV, a cooperative regional partnership of federal and state wildlife agencies, conservation groups and private industry, is aimed at conserving bird habitat in a six-state region, including eastern New Mexico where playas are located primarily on private land throughout the eastern half of the state. Over the last few decades, many playas throughout the Great Plains were altered by property owners to accommodate farming and ranching. The biggest threat to playas is sedimentation, or when rain or irrigation runoff carries loose soil from surrounding cropland into the playa basin, gradually filling it, according to PLJV. This reduces the amount of water a playa can hold—for wildlife use and for the aquifer.

Playas are filled when there are large rainstorms, and they lose water through recharge to the aquifer and evaporation, said Anne Bartuszevige, conservation science director with PLJV.

In New Mexico and Texas, there is another similar wetland sometimes mistaken for playas: salt lakes.

Salt lakes used to be filled by springs from the aquifer, explained Bartuszevige. “Today, many of those springs have dried up so salt lakes are often filled by runoff from rainstorms. However, because all the water is lost through evaporation, these wetlands get very, very salty.” (It is important to note that the water in salt lakes does not percolate down and help recharge the aquifer.)

In addition, salt lakes also have different plants and insect species than playas. “You can tell the difference between a salt lake and a playa from the ground by the presence or absence of a salt crust,” she said. “Salt lakes will have a white crust of salt remaining after the water evaporates. Dry playas do not have that.”

Another unique aspect of playas: unlike other wetlands, playas are low spots on the landscape that don’t connect to other outlets such as rivers, she explained. “They’re not part of a larger wetland complex where water flows across the surface of the land,” she said. “Really, they just gather water that runs downhill.”

And when that rainwater gathers exposed soil or sediment, the playas get filled in. Removal of this sediment, as well as planting native grasses that act as buffers to sediment, would enable playas to function properly, hold more water, and provide critical wildlife habitat in this semi-arid landscape.

***

Rustay has been an avid birder for as long as he can remember. His interest in playas began with his interest in birds. “Playas were a place to visit because of all of the birds there,” he said, noting how his interest in birding eventually led to him pursuing a career in habitat conservation.

In the eastern plains, he noted, birds are used to not having much water. A bird such as the lesser prairie chicken can get moisture from insects and drinking dew early in the morning, he explained. However, having a playa wetland there with water can be helpful as they have shown they are important for egg production. Playas also provide food and shelter for migrating waterfowl such as ducks and sandhill cranes and shorebirds such as American avocets and black-necked stilts. Many of these birds roost as far north as Canada but use New Mexico’s playas as stopovers on their journey south.

Austin Teague, southeast regional wildlife biologist with the Department, notes that playas are important for all wildlife on the plains. “Playas not only provide habitat for countless animals but are literally one of the only natural places where animals can get water from a source other than plants,” he said. He noted that ranchers put out drinkers for their livestock that also draw wildlife even as artificial water sources.

In the end, playas are ultimately where animals get their water from and where other wildlife can thrive. “If there weren’t playas, there would hardly be any amphibians in the shortgrass prairie ecosystems,” he said.

Teague, who is also the Department’s representative on the PLJV’s breeding bird monitoring advisory committee, noted that if landowners want to restore their playas, recharging definitely benefits them because the aquifer is compartmentalized and water filtering into the aquifer beneath their property will remain there for their use. “Whoever is restoring a playa on their land will see direct benefits,” he said. “If the aquifer dries up, no one would have water to irrigate their crops, or even live out there.”

Pronghorn, in particular, visit playas frequently when they have water, said Anthony Opatz, pronghorn biologist with the Department. “Any time there’s water on the landscape, pronghorn will find it,” said Opatz. Although pronghorn often drink from stock tanks set out by ranchers because they are a more consistent water source than playas, playas provide wildlife “good, clean water” and support surrounding buffers of nutritious forage.

The role playas have in sustaining life on the plains is best understood when viewed from above. Aerial photographs in the southeast reveal a view of a landscape filled with these water sources, that, according to biologists, are crucial to an ecosystem that will only thrive if there’s a place for the rain to collect.

“Playas are ephemeral wetlands, and all wetland types together comprise only less than two percent of the landmass in New Mexico,” said Rustay. “A lot of people who drive through the flat portions of the United States say there’s nothing here. My comment is, you’re just looking at them from the cars, driving at 75 miles per hour. You have to get out into the grasslands and the playas to see their beauty.”

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations