As the manager of more than 40 wildlife management areas and other properties around New Mexico, the Department of Game and Fish is not just responsible for protecting fish and wildlife; it’s also responsible for protecting important cultural sites.

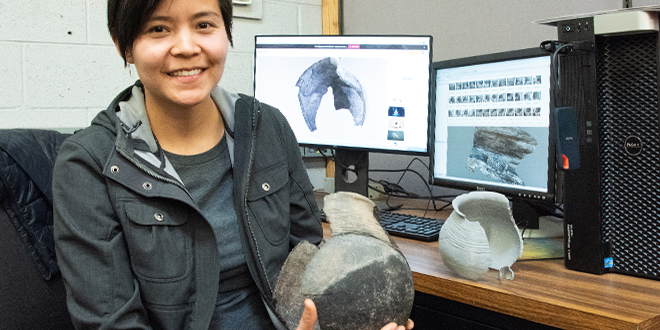

While she was a graduate student at the University of New Mexico, Adesbah Foguth, a member of the Navajo Nation from Lukachukai, Ariz., helped the Department protect those sites and artifacts with technology. She focused her research on the use of photogrammetry—the science of taking measurements from images—in archeology and generating three-dimensional, or 3D, models of artifacts.

“The purpose of doing photogrammetry is to preserve archeological artifacts that are fragile and are in danger of deterioration from being exposed,” Foguth explained, holding up a model of a jar from La Joya Wildlife Management Area she had glued together from pieces. “As you can see, this artifact here is extremely fragile. It’s been resisting my attempts to glue it together, so rendering a digital image has a lot of potential for archeologists who research and share these images digitally.”

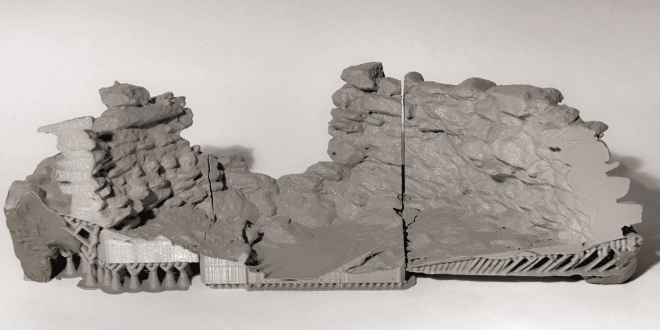

Above: 3D printed model of jar from La Joya WMA. Department photo by Martin Perea.

Jack Young, archeologist and tribal liaison with the Department, who called Foguth’s work “cutting edge,” noted that not only does her work help to preserve artifacts, but the 3D models help researchers see and measure things that may not be so apparent to the naked eye.

“This provides a way for the general public to experience archeology without the artifact being endangered by a lot of people handling it,” he said.

Documentation is crucial for archeologists, she said, adding that it’s “the key to good archeology.”

Still, she doesn’t think photogrammetry will ever replace hand sketches or two-dimensional photos. “Archeologists really love to keep all the records possible for future researchers who go back and look at what was recorded in the field and in the lab. But, one of the biggest benefits of photogrammetry is it doesn’t waste any time in the field. Time is money in the field.”

In the future, Foguth hopes to use this technology as a way to share thousands of artifacts that are currently in storage with the public. She has since graduated from UNM with a master’s in public archeology and is now working as a park ranger for the Bureau of Land Management at Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument.

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations