Certain places in our collective consciousness seem to exist because they have been the subject of books. The Four Corners belong to Tony Hillerman; the Gila River to Rev. Ross Calvin; and the Pecos Wilderness to the legendary conservationist and former director of the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, Dr. Elliot Barker.

But no one ever wrote a book about Dexter, New Mexico.

You may have never heard of the little village that exists primarily to service dairy farms and ranches. Dexter sits in the shortgrass prairie in Chaves County, overshadowed by its taller sibling, Roswell, a mere 15 miles distant. State Route 2 bisects Dexter, lying pike-straight on a section line like a yellow-striped gray-black ribbon. Pivot-irrigation sprinklers spin slowly over the rich alfalfa fields that feed local dairy cows. Velvet-green crop circles dot the flat countryside and tilt gently toward the Pecos River that bends within walking distance.

* * *

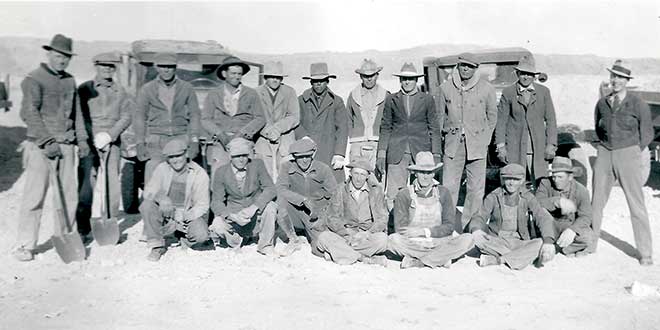

Dexter’s obscurity belies its significance in conservation. It is home to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Southwestern Native Aquatic Resources and Recovery Center, situated on the east edge of town. It is there because of the water. The federal fisheries facility lies on a rise barely perceptible. On a topo map, the contour lines spread widely. The same map shows a good number of rectangular ponds packed in a small space. The facility sits on a square-mile of land where artesian water was the natural defining character. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) acquired the property in 1931 from the New Mexico Game Commission for the express purpose of raising fish.

For nearly 90 years it has done that, growing fish for stocking waters from west Texas to southern California and points in between. Fish species such as largemouth bass, smallmouth bass, channel catfish, bullhead catfish, bluegill, redear sunfish and black crappie were long the mainstay.

Through the years, the facility has gone through a few name changes that in true essence reflected its changing mission: “fish-cultural station” became “national fish hatchery” which gave way to “fish technology center.” Today, the facility’s scientists fully immerse themselves in conserving some of the rarest fish species found in the American Southwest, says station director, Manuel Ulibarri.

Ulibarri, a native of Santa Rosa, got his start in conservation with New Mexico Department of Game and Fish. He learned trout and walleye culture at Rock Lake Fish Hatchery while still in high school. He studied at Western New Mexico University and New Mexico State University, and then worked at several national fish hatcheries before landing in Dexter nearly 19 years ago. Rare, native southwestern fish species were on station when he arrived.

“This facility started a transition to endangered species dating back to before the Endangered Species Act became law in 1973,” said Ulibarri. “It was quite evident back then that some native fishes were in trouble. Today, we hold 14 species that are imperiled to some degree—fishes found in nature in remote desert ciénegas to those in the fast, heavy flows of the Colorado River.”’

These native fishes range from tiny desert-dwelling fish to the world’s largest minnow.

“Desert pupfish turn a stunning electric blue when they get ready to spawn—they’re thumb-sized and they look playful, almost cartoonish,” said Ulibarri. “Then there’s Colorado pikeminnow, native to the Colorado River and its larger tributaries, including the Gila and San Juan rivers. They have the capability to grow to six feet long. What the two fish have in common is their rarity in nature; that’s why they’re here.”

The following fact underscores that rarity: the Colorado pikeminnow shared the same habitats and suffered the same peril as three other Colorado River Basin fishes, the bonytail, humpback chub and razorback sucker. Habitat loss from altered stream flows have greatly diminished their numbers in nature.

“The only place left that all four Colorado River species swim together is here,” said Ulibarri. “The adult fish all have amazing body shapes for life in voluminous river flows. Form follows function. Humps on their nape are a built-in keel, and it’s always impressive to see when we spawn the fish.”

* * *

The sound of running water never ceases inside the hatching house. Continual splashing becomes a murmur akin to a large gathering of people engaged in conversations. The sounds fade to the background. Water percolates through stacks of shallow trays where eggs that look like gobs of farina cereal incubate, their tiny eyes visible through the shells. They soon wiggle free and grow rapidly, eventually making their way to the outdoor ponds. Water flows through three-foot-deep rectangular concrete raceways and eight-foot-diameter tanks hosting a variety of fish species awaiting time to spawn.

Razorback sucker is the first fish to ripen to spawn in the spring, soon followed by Chihuahua chub, a minnow found only in the Mimbres River flowing through the Mimbres Wildlife Area. The whole lot of 14 species spawn in captivity in the hands of biologists by the onset of summer.

Geneticists at the station carefully arrange spawning pairs of all species to ensure that parents are not related. That further ensures that offspring are genetically robust, and best suited to face the rigors of the wild where they will eventually go. Health is a principal concern. Fish health pathologists on staff frequently assess the well-being of the stocks on station. These pathologists, in fact, assess fish heath in state and federal hatcheries and in wild fish populations throughout the southwest.

The Southwestern Native Aquatic Resources and Recovery Center employs 22 people from a variety of disciplines, folks who keep the water flowing and the fish swimming and breeding. Staff scientists frequently publish their research in rigorous scientific journals that advance knowledge of fish health, genetics, conservation and culture techniques that apply to imperiled, commercial and sport fish species.

“The fishes we have here are part of our southwestern heritage,” said Ulibarri. “They each have a unique intrinsic value. They possess the imprint of nature from the places from which they arose—and that’s irreplaceable.”

Dexter may not have its Hillerman or its Barker but the nearly 90-year-old fisheries facility has authored an imprint in conservation all its own.

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations