New Mexico Wildlife (Fall 2004, Vol 49 Num 3)

Making Tracks: A Century of Wildlife Management, Part 8 of 9

Flowing through controversy: reservoirs offered mixed blessings for fish and fishermen

By John Crenshaw

Former Public Affairs chief, New Mexico Wildlife editor, and game warden, retired in 1997.

New Mexico’s first territorial game warden was appointed in 1903. There was no school of wildlife management, no state fish hatchery system and few, if any, Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep and elk.

The Department of Game and Fish has grown out of that first appointment to an agency authorized to employ 286.5 individuals. Their mission is to provide the people of New Mexico with a flexible system of fish and wildlife management that perpetuates the state’s vast wealth of wildlife species.

During the last century of challenge, the agency has restored elk – too well in some minds; put Bighorn sheep back on the mountains; constructed and reconstructed six fish hatcheries with a seventh in the works. Along the trail the Department has assumed new responsibilities as the public’s desire to retain its wildlife heritage embraced species once believed less than desirable.

With this 9-part series “A Century of Wildlife Management” from New Mexico Wildlife, we look at the tracks this outfit made during its first century. Those tracks lead to the highest peak, and to the hottest desert, anywhere wildlife might need a helping hand.

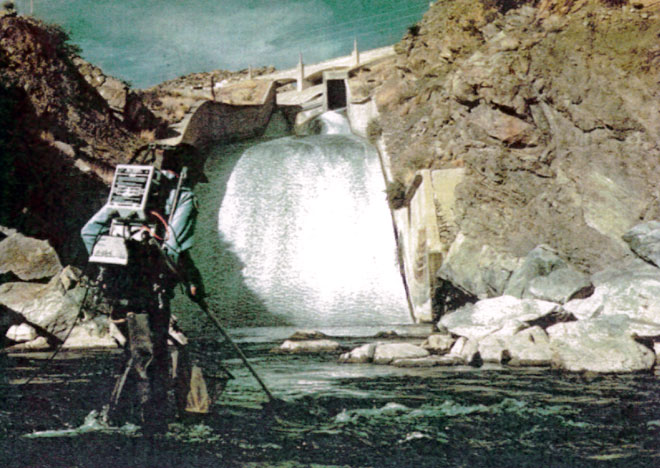

Above: Navajo Dam created the excellent, and accessible, fishing on the Quality Waters of the San Juan River. Photo: NMDGF.

Mixed blessings for fish and fishermen

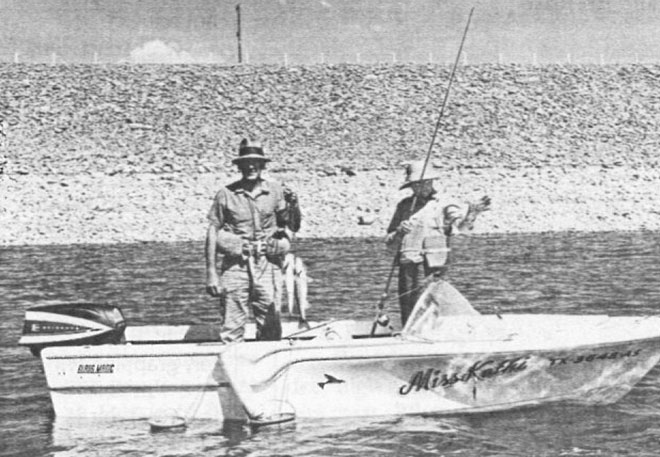

These excerpts from a June 2004 fishing report illustrate how much today’s anglers take for granted the fishing waters and the fish in them. We race bass boats up Elephant Butte, quietly troll the cold waters of Eagle Nest or wade among the very large and numerous trout in the San Juan River’s quality water section.

ELEPHANT BUTTE – Top water action continues to improve for striped bass as well as for white bass… anglers trolling umbrella rigs are having some success from early to mid-morning. Fishing for black bass is fair using jigs, tubes and grubs.

EAGLE NEST LAKE – Best reports from anglers trolling a variety of spoons and spinners. They managed to catch a few kokanee.

SAN JUAN – Water flow below Navajo Dam is 366 cfs. There are some good caddis hatches… fishing rated as excellent.

It’s as if those fish and fisheries have been here forever.

But the same report would mystify the angler of June 1904. Where we see lakes, he would have seen free-flowing rivers. Where we see cold, clear quality trout water, he would have seen a meandering, muddy stream better suited for catfish. He would recognize black bass – though perhaps not umbrella rigs – but white bass? Striped bass? Kokanee salmon? Neither would he have had much acquaintance with lake trout, walleye or northern pike, among others introduced into the 20th century reservoirs. And busy fish managers quickly moved species such as black bass and sunfish, native only to warm southern New Mexico streams to the new lakes, as well; anglers caught them where the fish had never been before.

On the brink of a spree

Neither the dams, lakes, tail-water fisheries nor those exotic fish existed in New Mexico a century ago, but the territory in the early 1900s was poised on the brink of a dambuilding spree that continued well into the mid 1970s.

Most dams answered homesteading farmers’ clamor for irrigation water. Some controlled floods that washed away not only pioneers’ early irrigation systems, but sometimes pioneer homes and the pioneers themselves. Some provided water for railroads and towns. Some simply captured silt before it roiled downstream and settled in other, older reservoirs.

Privately owned companies, acequia and ditch associations built some of them, sometimes with government assistance. There are dozens of privately built irrigation reservoirs scattered around New Mexico, ranging in size from tiny Morphy through Storrie to Bluewater and Eagle Nest-sized lakes, for instance. But the federal government built the really big ones, like Elephant Butte in the teens, Caballo, Conchas, El Vado and Sumner in the ’30s, Heron, Abiquiu, Cochiti and Ute in the 1960s and 1970s, and Brantley – to replace the 90-year-old and silted – in McMillan – in the early 1990s.

“There are some good and bad things about the dams, depending on your philosophy,” says Harold Olson, a former director of the Game and Fish Department who started with the agency as a fisheries biologist in 1959.

Better fishing, for new and different kinds of fish could be on the good side; severely altered native ecosystems could be on the other.

Navajo Dam can serve as one example.

Hear ’em rattle

Olson developed the fish management plan for the San Juan River in the early 1960s. He had a front-row seat as the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation dammed it to create Navajo Reservoir as part of the much larger Colorado River Storage Project.

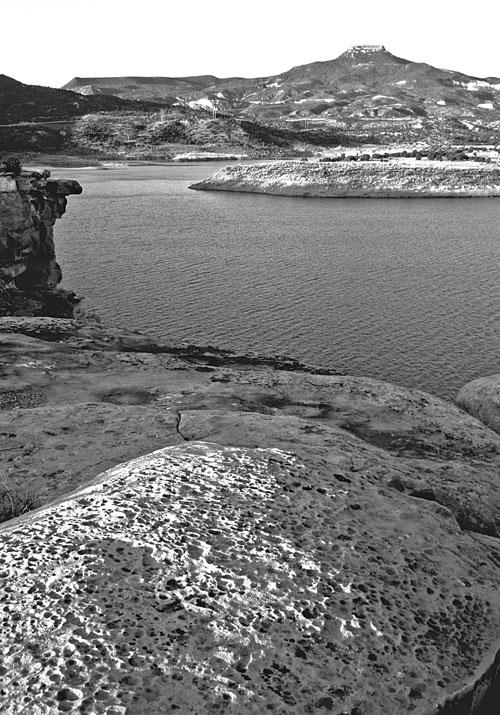

Completed in 1963, Navajo Dam is 402 feet high and seven-tenths of a mile wide at the crest. When Navajo Lake is full, it holds more than 15.7 million acre-feet of water, occupies more than 15,600 acres and backs up water for 35 miles on the San Juan River, 13 miles up the Pine River and 4 miles up the Piedra River into southern Colorado.

That is a huge amount of water, with huge potential.

“There are so many different habitats available; there’s warmer water at the surface, cooler water down in the depths. The thermocline is quite a ways down, so you weren’t talking about oxygen depletion until you got down to 100 feet or more,” Olson says.

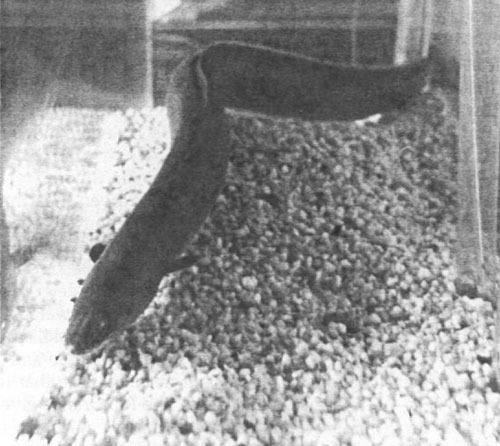

“So there are just all kinds of habitats there for everything – fish as different as kokanee salmon, algae eaters that cruise around the depths in the center of the lake, or shoreline dwellers like largemouth bass and smallmouth bass, that favor crayfish. So it provides a combination of things that can satisfy a lot of different fishermen,” he says.

The Department did not stock that variety right away, however. Tradition got in the way.

“Roy Barker was chief of fisheries,” Olson recalls. “And no disrespect, but he only believed in trout – they were the only fish that were fishable. So, when we first started at Navajo, Roy Barker wouldn’t consider anything except trout in that lake. It was a full six or eight years after the dam caught water that we put anything besides trout in there.”

Now anglers can hunt for largemouth and smallmouth bass, jig for crappie, dunk worms for bluegills or waterdogs for catfish, bankfish for trout or troll for kokanee.

The dam wrought big changes downstream, as well.

“The San Juan changed from a muddy, kind of warm catfishing stream to a cold-water stream from Blanco up,” Olson said. “When Navajo first was impounded, it was only about 60 feet deep. The water wasn’t a whole lot colder – around 60 to 65 degrees when they released it, but a lot of sediment settled out in the lake bed, so it was a whole lot clearer.”

The invertebrate population exploded then, at first with large snails.

“Some of those big trout they caught in the early days on the San Juan River were just full of those snails, so full you could almost hear’em rattle,” Olson says.

The lake grew much deeper. Water shot from 200 feet below the lake’s surface at 45 to 50 degrees; insect life displaced the big snails and still feeds a big-trout fishery that has earned international acclaim.

The San Juan’s tight restrictions – artificial baits, barbless hooks, minimum size and bag limits and a catch-and-release stretch immediately below the dam – seem sacrosanct now. But not 30 years ago.

They ate our lunch

“We had some real wars in the early ’70s when we made that stretch fly-fishing only, “Olson says. “People were just aghast that we would do things like that. They were used to dunking worms in Texas Hole and wanted to keep right on doing that. They ate our lunch, but we held on. Now it’s pretty well accepted.” On the other side of the coin, Navajo and other dams in the project blocked migration routes for the native Colorado pike minnows, which travel up to 125 miles to spawn. The controlled water releases altered seasonal water flows, especially spring floods. The cold, clear water flowing from the dams favored trout, but is far different from the warm, sediment-laden water where the pike minnow evolved and the newly introduced fishes prey on its young. Only a few still exist, and state and federal governments both list the species as endangered.

Dams wrought similar changes on the Rio Grande, helping drive the Rio Grande blunt· nose shiner into extinction. They figured in the extirpation of the shovelnose sturgeon and American eels .from the state and helped put the silvery minnow on the endangered species list. Dams on the Pecos and Canadian drainages had comparable effects on other native fishes.

When people built most of these dams, the federal Endangered Species Act did not exist. It would figure significantly in planning any future dams now and recreational potential such as fishing and boating also would figure prominently.

It hasn’t always been that way. The biggest and one of the oldest examples plugs the southern Rio Grande near Truth or Con· sequences.

Burning in the sun

Engineers began the Elephant Butte project in 1906 with the Leasburg Dam and canal and put finishing touches on the centerpiece, Elephant Butte Dam, a decade later. The complex eventually grew to include six diversion dams, 139 miles of canals, 457 miles of laterals, 465 miles of drains, a hydroelectric plant and a second reservoir dam at Caballo, completed in 1938.

The complex now includes four state parks – Elephant Butte, Caballo, Leasburg and Percha – and a year-round fishing and outdoor recreation industry. Each Memorial Day weekend, winter-weary New Mexicans and Texans flock to Elephant Butte Lake – fishing, sailing, house-boating, water skiing, zipping around on watercraft, camping, picnicking, sunning on its beaches.

Anywhere from 85,000 to some 100,000 people show up – making the park one of the largest cities in New Mexico for a few days.

But the water they frolic in is not theirs. The lake came into existence as an irrigation storage reservoir, and farmers of the Elephant Butte Lake Irrigation District have a long-standing privilege to call for it to water their crops. The state of New Mexico, under the Interstate Stream Compact, is obligated to deliver certain amounts of water downstream to Texas, too.

Water levels at Elephant Butte and other irrigation reservoirs can and do drop suddenly. Frequently, spring irrigation drawdowns at Elephant Butte leave black bass eggs burning in the sun. Less frequently, but more noticeably, those drawdowns leave anglers and boaters burning, too.

One of the most recent examples happened in 2001 on the Pecos River, when the Carlsbad Irrigation District, quite legitimately, called for water deliveries from Sumner and Santa Rosa reservoirs.

“Responding to a call for water from the Carlsbad Irrigation District, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation intends to drain most of the water out of the Santa Rosa and Fort Sumner reservoirs over the next two weeks,” the Associated Press reported.

“That will bring to a halt fishing and boating at Santa Rosa – one of the state’s most popular lakes – and it could spell trouble for a small fish native to the Pecos River, the blunt-nosed shiner,” the story continued. Boat· ers, anglers, and the local businessmen who depend on them all objected, but water deliveries went as scheduled.

Except for chile

Winter snows and summer rains blunt or remove that trauma in some years, but the conflict is systemic. The State Parks Division again closed Sumner Lake to boating in mid-2004, when drought and irrigation demands dropped it to five percent of capacity.

Former State Game Warden Elliott Barker rejoiced in 1934 when the Department of Game and Fish negotiated free public access to the new El Vada Lake from what is now the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District. The Department stocked the fertile new lake heavily with rainbows in 1935.

“Survival and growth were unprecedented… for several years after that, we produced the best fishing both in the lake and stream below to be found in the nation,” Barker wrote.

The drought of the 1930s gave impetus to dam building. But drought struck New Mexico again in the 1950s, and Barker did not rejoice.

The controlling federal agencies and irrigation districts in 1952 drained “the last acrefoot of water from Alamogordo (now Sumner) and El Vado lakes when retention of a very small amount would have saved the basic fishing resources,” Barker wrote.

“Elephant Butte Lake was saved from a like fate by a federal court injunction brought by the City of Truth or Consequences requiring 15,000 acre feet to be retained,” he wrote.

Harold Olson, as a fisheries manager and one of Barker’s successors as agency director, grappled with similar issues.

“I’m absolutely convinced that the water in a reservoir is more economically beneficial to the public than water in an irrigation field okay, except maybe for chile,” Olson says. “But we’ve been irrigating for so long, it’s kind of a traditional thing. What still bugs me is that you have to divert water to keep your water rights. The state cannot buy it and keep it in the stream for in-stream flows. If the state buys it, pretty soon they would lose it because they’re not ‘using’ it. And we still haven’t got that fixed.”

In the meantime, recreation, fish and wildlife may continue to play second fiddle – with some generally small but notable exceptions. The Game and Fish Department developed some of its own lakes and put fish, fishermen, wildlife and recreation at the front of the line. It really hit its stride after substantial and long-term funding became available under the PittmanRobertson Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration and Dingell-Johnson Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Acts became law in the 1930s and 1950s, respectively.

For instance, the agency built Fenton, Hopewell, Clayton, Quemado, Snow and Roberts lakes. It improved the dams at McGaffey and San Gregorio. It leased public access to numerous other lakes – Storrie, Morphy, Ramah, Monastery, Power Dam, Green Meadow, Maddox, Bonito, Bill Evans and Bear Canyon lakes among them.

It outright purchased others – Charette Lakes was one bargain. It bought McAllister Lake from the San Miguel County Game Protective Association, which had moved swiftly to buy it before it went into permanent, private ownership – an early version of The Nature Conservancy.

Eagle Nest, purchased in 2002, surely is tbe crown jewel.

And the Game and Fish Department purchased or leased access to stretches of fishing water along streams in every part of the state, including the storied San Juan River.

Biologist Olson was there when a stretch of the San Juan became Navajo Lake:

“l did some law enforcement work at Navajo Dam, and a pre-impoundment study on the river,” he says. “Then as the lake started filling up, I measured the changes in water quality. It was kind of fun, watching the reservoir fill up and the changes that took place.”

But, he mused, his attitude has evolved:

“Tm not really a proponent of big dams anymore,” he said.

More people feel that way now than in the 1920s or 1950s, certainly, and new dam construction often is delayed or blocked altogether. In the meantime, anglers flock to the existing reservoirs and enjoy the bounty of tail-water fisheries below them. For those seeking something else, there are a few places to retreat from controlled flows and flat water.

One is the Gila River, the only sizable stream in the state that is not dammed at some point in New Mexico.

Another is the upper Rio Grande.

New Mexico’s largest river runs unimpeded some 60 miles from the New Mexico-Colorado border to its steep-walled canyon’s mouth at Velarde. Strenuous hikes from the upper canyon’s rim -and back – deter casual fishermen, and the unpredictable waters of a free-running river frustrate even skilled anglers. But for those seeking solitude and the big brown trout and northern pike that lurk in its runs and riffles, the Rio Grande gives a taste of wilderness fishing with an un-damned flavor of freedom.

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations