New Mexico Wildlife (Summer 2004, Vol 49 Num 2)

Making Tracks: A Century of Wildlife Management, Part 7 of 9

Of fish and men: state waters are stocked with natives, exotics, and politics

By John Crenshaw

Former Public Affairs chief, New Mexico Wildlife editor, and game warden, retired in 1997.

New Mexico’s first territorial game warden was appointed in 1903. There was no school of wildlife management, no state fish hatchery system and few, if any, Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep and elk.

The Department of Game and Fish has grown out of that first appointment to an agency authorized to employ 286.5 individuals. Their mission is to provide the people of New Mexico with a flexible system of fish and wildlife management that perpetuates the state’s vast wealth of wildlife species.

During the last century of challenge, the agency has restored elk – too well in some minds; put Bighorn sheep back on the mountains; constructed and reconstructed six fish hatcheries with a seventh in the works. Along the trail the Department has assumed new responsibilities as the public’s desire to retain its wildlife heritage embraced species once believed less than desirable.

With this 9-part series “A Century of Wildlife Management” from New Mexico Wildlife, we look at the tracks this outfit made during its first century. Those tracks lead to the highest peak, and to the hottest desert, anywhere wildlife might need a helping hand.

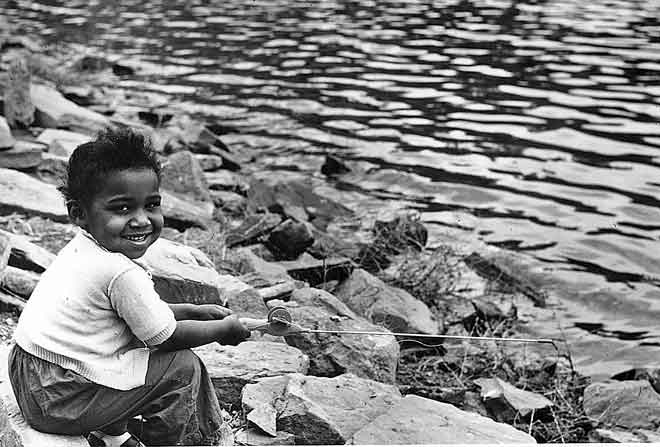

Above: Planting trout in the Rio Grande Gorge. Photo: John G. Whitcomb.

Of fish and men: state waters are stocked with natives, exotics, and politics

New Mexico is a dry state, suffering long spells with little precipitation, yet intermittently jolted by scarring floods—conditions that prehistoric New Mexicans struggled with and that shaped our modern landscape and culture, including our fish and fisheries.

Native Americans caught and ate fish here – the bones are in their village middens. And like the Europeans to come, those early human activities affected New Mexico’s chronically water-challenged drainages. A notable prehistoric example was the Anasazi’s denuding of the Chaco Wash area for building materials and fuel, contributing to their cities’ demise.

Spaniards brought more extensive irrigation diversions and ditches, livestock grazing that altered vegetation in the drainages and increased demands for building materials and fuel wood. All of these altered streams flows, increased siltation and raised water temperatures, which in turn affected the fish in formerly pristine streams.

The Spaniards, too, left fish bones in their trash piles – and with them clues to the fish life and water conditions of the times. One can hardly imagine it now, looking at the sandy bed of the Santa Fe River in the capital city’s downtown, but this stream once ran year-round. It held wild trout even after the Spaniards built the Palace of the Governors and trenched the Acequia Madre to irrigate their com, beans and chile.

Still, the human populations were as yet relatively small and their impacts still fairly limited and localized.

Steam-powered stocking

When Anglo settlers began arriving in greater numbers after the Civil War, they, too, looked to New Mexico’s creeks and rivers for fish. They brought with them cattle and sheep in numbers never seen before, plus the steam-powered technology of the late 1800s. Both wrought sweeping changes in New Mexico’s ecology and changed its fisheries forever.

The first big railhead reached Las Vegas in 1879, and within a few decades steel lines webbed the state. The trains hauled livestock, timbers, coal and people to open up the West.

They also hauled fish. New Mexico’s new settlers brought with them an exuberant mindset that however good things are, they can be made better. Stocking new kinds of fish was one of the ways. Building dams and diversions for irrigation and flood control was another. Building fish hatcheries was third.

They started the stocking in 1883 with carp, hailing them as a food and sport fish, but soon regretted that early action.

No one then regretted stocking rainbows from the Northwest. That began in 1896 at Bluewater Creek near Grants and Eagle Creek near Ruidoso, according to The Fishes of New Mexico, by James and Mary Sublette and Michael D. Hatch. Brook trout from the southern Appalachians, brown trout from Europe and a plethora of basses, perches and catfishes soon followed.

Hardly any drainage was left untouched. Milk cans full of fish fry and fingerlings from the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries’ hatcheries arrived regularly. When Page Otero became New Mexico Territory’s one-man game and fish department in 1903, fish stocking was established practice, and a basic set of fishing regulations was in place.

No drugs, explosives or seines

Those first laws were passed in 1897 and Otero likely helped draft them.

“The trout season was set for June through October with a six-inch size limit, and the bass season was June through January. The act prohibits possession of protected game and fish in closed season, and makes possession prima facie evidence of the same having been taken out of season,” wrote Elliott Barker, who served as State Game Warden for more than 20 years, in an unpublished history of the Game and Fish Department.

A key provision prohibited taking trout or other food fish by any means other than hook and line – no drugs, explosives, seines or nets were allowed. The law also prohibited fishing within 100 yards of dams and weirs – where fish would be unusually concentrated and vulnerable – or diverting water to take fish by stranding them in pools.

The laws of 1903 strengthened those earlier protections. It maintained the 6-inch minimum size limit and set the first bag limits – 15 pounds of trout or 25 pounds of bass.

A minimal start, perhaps, but those laws set the tone for times ahead. Open and closed seasons, size limits, bag limits and restrictions on fishing gear remain at the core of fishing regulations, since refined ad infinitum to address particular conditions or reach certain goals. Barbless hooks, slot limits and catch-and-release regulations were far in the future, but their origins lie in that initial legislation.

The sportsmen backing the new laws and pushing for enforcement saw fish as a recreational resource. Others still saw them as food first; recreation was the fish fry. Enforcement was difficult, but Otero did what he could.

“The Warden himself caught a party dynamiting some big holes in the Pecos River near Rowe to take trout.” Barker wrote of Otero’s early efforts. “The case received much publicity for dynamiting was not popular.”

A veritable harvest

Otero wrote in his first report that the Pecos River by that time held five species of trout: the native Rio Grande cutthroat, rainbows, brook and brown trout and Dolly Varden. He noted the weather had been dry and many streams had dried up during his first years in office but by spring of 1905, many streams were in bad shape because of floods. It’s a rare warden’s report, in the century since, that doesn’t repeat one or both themes – most often drought or near-drought.

Thomas Gable, who succeeded Otero as Territorial game warden and led the agency again after statehood, argued for license fees to help the Department operate more independently and continued lobbying for a hatchery.

He invoked the findings of early fisheries scientists to make his case in his report for 1909-1911:

“It is a well established fact that 95 percent of the eggs taken from fish and placed in the state hatcheries are successfully hatched, while only 10 to 12 percent of the eggs laid in the natural way in the mountain streams reach maturity,” he argued, adding that natural propagation in the state’s streams could no more supply people’s demand for fish than natural growth could supply the demand for fruit. Gable also argued for hatcheries as an investment in New Mexico’s future prosperity.

“Colorado is reaping a veritable harvest from tourists, and furnishing great sport for the home angler,” he wrote. “This state has established nine hatcheries, which are maintained by legislative appropriation, this being found necessary to meet the constantly increasing demand.”

Foreign fishes

Gable’s prediction about sport fishing’s value was remarkably prescient. Nationally, the 2001 figures were $35.6 billion in expenditures, and 557 .4 million days of recreation, according to a study by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Anglers spent about $176.5 million on fishing-related travel and equipment in New Mexico that year, enjoying nearly 2.5 million days on the water – not bad for the third – driest state in the nation.

The fish being stocked were in large part foreign to the waters of New Mexico, spelling trouble for native fishes. In the case of trout, for example, the rainbows cross-bred with the native Rio Grande cutthroat and Gila trout. Brook trout competed with them for space and food, and brown trout competed with and preyed upon the natives.

Although probably unaware of problems with predation and competition, Gable recognized the hybridization. He found virtue in it.

“These two varieties cross very readily, so that it is difficult now to find these distinct species … It has become a well-known fact to all students of fish life and culture, that crossing is beneficial,” he wrote. He went on to claim that “constant interbreeding had tended to decrease the size,” of native fish but with the introductions “there has been a decided and very noticeable change in the size and condition of these fishes in our waters.”

Although Gable saw hybridization as benign – even beneficial – it helped put the native Gila trout on state and federal endangered species lists years later, and it reduced purebred populations of Rio Grande cutthroat to mere remnants in scattered headwaters.

Gable, though, was simply a man of the times, and the times and men demanded that fish be stocked for fishermen. During his first tenure, New Mexicans distributed well over a million trout fry and fingerlings, plus catfish, black bass, rock bass, ring perch, sunfish and crappie into dozens of waters, primarily national forest streams and the numerous little man-made ponds and small lakes beginning to dot the territory.

Where trucks fear to tread

Gable’s report coached fish stockers – many were private landowners – on how to keep the delicate young fish alive from railhead to water. Those first hauls were by horse-drawn wagon or pack mule, followed by cranky Ford trucks. Now, modem vehicles equipped with oxygen tanks and other refinements make most hauls; but fisheries managers also use helicopters, airplanes, rafts, bass boats, backpacks – and equines – to take fish where trucks can’t go.

Gable, with at least a nominal operating budget, could buy fish and pay for their transport.

Most of the license revenues came from hunters, but anglers also were beginning to pay their own waybarely. The laws of 1909 required nonresidents to purchase a $1.00 license. Residents fished for free until 1915, when the legislature imposed a $1.00 license fee – but exempted trout fishermen, the great bulk of anglers.

But big changes were in the works. The sportsmen of the Game Protective Associations and state game wardens alike were lobbying for hatcheries, equitable license requirements and creation of a state game commission citizen’s body to oversee the department.

“By far the most important legislation was that requiring a license for residents to fish for trout, culminating ten years of effort,” Barker wrote of 1919’s legislation. “There was no resistance to the resident trout licensee, instead, sportsmen generally were jubilant because it gave the Department considerably more funds to operate on.”

The agency sold just over 1,100 licenses in 1918, before the law went into effect. That went to more than 5,600 by 1920 – and to 243,000 in 2002.

The laws of 1921 created the long-sought State Game Commission. The three-member board quickly purchased the site of Lisboa Springs Hatchery north of Pecos for $5,000 and began construction.

“By December brook trout eggs had been received and placed in the hatchery troughs,” Barker wrote in 1970. “Thus the Department’s fisheries programs and activities began – destined to grow year after year and the end is not yet in sight.”

Black-spotted trout eggs

Lisboa Springs was a solid, long-term purchase though extensively renovated and remodeled several times since, it remains a mainstay of trout production in New Mexico.

Not so some other hatcheries from those early days. In 1923 the commission authorized $650 to build the one-person Jenks Cabin hatchery on the Gila River, 25 miles from any road. Crews mule-packed in 325,000 black-spotted trout eggs – cutthroats of some variety – to hatch into fry, soon planted in 11 area streams. “The Jenks Hatchery served a good purpose for about ten years but was a costly and difficult operation,” wrote Barker.

The commission and warden built other small hatcheries in the early 1920s, authorizing one on Eagle Creek in Lincoln County, another west of Chama on what is now the Sargent Wildlife Area and a third near Taos.

In his unpublished history, Barker dismissed those operations as having been established because of political pressures, “sites where the water supply was so limited and unsuitable that they had to be abandoned and replaced…”

Barker took that up when he became State Game Warden in 1931, but some sportsmen viewed the closures with suspicion.

“It is with considerable concern that I note the apparent decision of the Commission to abandon some of the present sites and build new hatcheries on new sites,” wrote Fred Pettit, a leader in Albuquerque’s Game Protective Association in 1931.

“Our Game Dep’t is top heavy in fish culture. It would be well to go extremely slow in any such changes as seem contemplated, for I am not convinced of the soundness of many of the promises outlined in your report. Neither am I convinced that the present sites are as unsuitable as reported.”

Despite such misgivings, the Department shut down the smaller operations over time and built hatcheries at all three of its newly contemplated sites.

Construction began on Seven Springs Hatchery, north of Jemez Springs, and on Parkview Hatchery, south of Chama, in 1932. Construction at Glenwood Springs, north of Silver City, soon followed. All are still operating – the Jemez Springs unit now dedicated largely to rearing pure-strain Rio Grande cutthroats.

In 1941, after testing the flow and quality of water from a set of springs along the Red River below Questa, the agency built Red River Hatchery, completing the set.

Warmwater hatching

All those hatcheries produced trout by the tons as years progressed. But anglers, the State Game Commission and the agency all agreed the state also needed other hatcheries to produce largemouth bass and other warmwater fish.

“We have in this state a very considerable amount of water adapted to the various species of warm water fishes, which has been given scant attention, as far as artificial stocking is concerned,” wrote State Game Warden Edgar Perry in his report for 1929-1930.

To rectify that, the agency acquired Nine Mile Lake near Dexter in 1929 and stocked it with breeding-age largemouth bass and sunfish.

“It was very inexpensive to construct, has practically no operating cost, and in 1929 produced an almost unbelievable number of young fish,” Perry wrote. Despite real problems retrieving young fish from the ponds dense algae, crews planted 14,000 bass and 21,500 sunfish in southeastern streams and lakes from that first crop.

The state had held off building a full-scale bass hatchery because “for the past several years we have seemed to be on the verge of acquiring a Federal hatchery of this class,” Perry reported. “This is at last an accomplished fact.”

The state phased out its now-redundant operations at Dexter after the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries built a warmwater fish hatchery there in 1931.

The federal hatchery produced game fish such as bass for decades but began a unique mission in 1978. It is now the nation’s only facility dedicated to studying and rearing endangered fishes, such as the razorback sucker and Colorado squawfish, for restoration to their former streams. It works in conjunction with the Mora National Fish Hatchery and Technology Center, built in the mid-1990s as a research and technological development facility.

After launching the Dexter facility, the federal government followed up with warmwater hatcheries at Elephant Butte and Santa Rosa.

Both of those are closed, but the state began using Santa Rosa’s ample water supply to operate Rock Lake Rearing Station in 1964. It added warmwater hatching facilities there in the early 1970s to hatch walleye eggs that Department crews annually net at Conchas and Ute Lakes.

The state soon will expand that warmwater hatchery operation. The Game and Fish Department purchased 30 acres and water rights to build a new warmwater fish hatchery adjacent to the Rock Lake facility.

Predators and parasites

Warden Gable’s opinion that hatcheries are necessary to satisfy anglers’ demands carries weight still, but aquaculture carries risks.

“…we suffered an epidemic of a parasitic disease at the Lisboa Springs and Taos hatcheries the spring of 1929, losing some 300,000 small fingerling fish,” Warden Perry wrote in his annual report.

Such a wealth of fish life also attracts fish predators. Barker reported in his 1935 report that Jenks Cabin production was down “due to excessive loss by water snakes and frogs.”

Hatchery managers also have a never-ending feud with fish-eating birds, but birds may do more than carry off a few fish. They also may carry fish diseases.

“New Mexico buried 200,000 fish last week in Pecos – rainbow trout worth at least $120,000 – the first collateral damage in a fight to slow the march of whirling disease,” wrote Ian Hoffroan in the Albuquerque Journal in December 1999. “Literally tons of the trout looked healthy, but enough spun aimlessly in the water in the dead-on signature of whirling disease.”

Most probably brought in by a diseased fish from an out-of-state hatchery, but possibly borne in by birds or on an angler’s boots, a parasite that had devastated rainbow and cutthroat trout fisheries elsewhere had slammed into New Mexico.

Biologists soon tracked it from Lisboa Springs into other major hatcheries, and eventually found it in popular trout waters in much of northern New Mexico - including the internationally famous San Juan River.

Those 200,000 trout destroyed to slow the disease’s spread were merely the first of thousands more hatchery fish to be buried in landfills. The agency continues its aggressive, sometimes controversial and very expensive fight to bring whirling disease under control – destroying diseased fish, decontaminating and extensively remodeling its hatcheries and requiring that fish imported from out of state be certified free of the parasite.

Some anglers now press for less reliance on hatcheries and more on natural production, and fisheries managers are responding. But Territorial Warden Gable’s early assessment – that hatcheries are a keystone of recreational fishing – still rings true and makes the whirling disease battle one worth winning.

Next issue: How a century of water development projects massively altered New Mexico river systems, fish and fishing, and how a deceptively simple tax altered fisheries science.

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations