New Mexico Wildlife (Spring 2003, Vol 49 Num 1)

Making tracks: a century of wildlife management, part 6 of 9

True crime: wildlife law enforcement comes of age in the 21st century

By John Crenshaw

Former Public Affairs chief, New Mexico Wildlife editor, and game warden, retired in 1997.

New Mexico’s first territorial game warden was appointed in 1903. There was no school of wildlife management, no state fish hatchery system and few, if any, Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep and elk.

The Department of Game and Fish has grown out of that first appointment to an agency authorized to employ 286.5 individuals. Their mission is to provide the people of New Mexico with a flexible system of fish and wildlife management that perpetuates the state’s vast wealth of wildlife species.

During the last century of challenge, the agency has restored elk – too well in some minds; put Bighorn sheep back on the mountains; constructed and reconstructed six fish hatcheries with a seventh in the works. Along the trail the Department has assumed new responsibilities as the public’s desire to retain its wildlife heritage embraced species once believed less than desirable.

With this 9-part series “A Century of Wildlife Management” from New Mexico Wildlife, we look at the tracks this outfit made during its first century. Those tracks lead to the highest peak, and to the hottest desert, anywhere wildlife might need a helping hand.

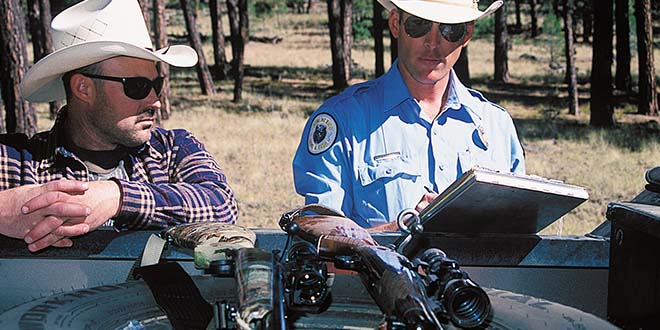

Above: Dan Brooks, Law Enforcement Chief, watches Sgt. Chris Neary fill out evidence tags. Photo: Martin Frentzel.

True crime: wildlife law enforcement comes of age in the 21st Century

“It’s like a murder case; only it’s not a person, it’s an animal. Officers have to collect the same evidence, by themselves, that you see a whole team of scientists doing in crime scene investigations,” said Dan Brooks, chief of the law Enforcement Division.

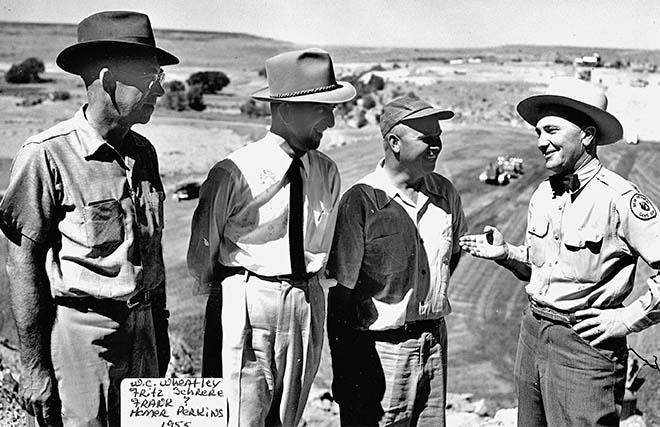

Game officers now have more tools – including forensic sciences – and more intensive training than their predecessors ever had, but the agency’s history is replete with good investigators. The early wardens often came from the ranks of cowboys, trappers and hunters. They usually were skilled horsemen, outdoorsmen and trackers, all skills they brought to their investigations. Homer Pickens, hired in 1931 as a lion hunter and eventually head of the agency after 1953, helped Pecos patrolman L. W. (Speed) Simmons investigate a typical case in the spring of 1941. Someone had tipped Simmons to an illegal deer kill in the Mora Flats area, where they rode to the crime scene.

“…we saw where a pickup truck had backed around and driven over a gopher mound,” Pickens wrote in his book, Tracks across New Mexico.” … judging from the location of the pickup, we were able to ascertain the trajectory of the bullet that had killed the deer. We found the slug embedded near the base of an aspen tree… It had mushroomed some and still had blood and hair on it. We followed the tire tracks down the slope…”

The tracks led to a ranch house.

“We… drove to the Justice of the Peace in Pecos, where we made out an affidavit stating that to the best of our knowledge there was an illegal deer concealed in the house. On the basis of this evidence we obtained a search warrant.”

When they served it, “We found the rifle on the bed under a quilt. In an adjoining room we found the hind quarters of a freshly killed deer.”

Guilty. $50 fine.

Science fiction and blood evidence

The Mora Flats investigation turned up enough evidence for a search warrant and turned up more at the house. Had the wardens needed scientific proof linking the spent slug to the particular rifle, they would have been at a loss. Molecular DNA analyses of blood or tissue samples simply would have been science fiction.

A little more than 30 years later, investigators could have sent the slug to the new State Police Crime Laboratory in Santa Fe, where firearms and tool marks experts would have proved the bullet had – or had not – came from the weapon found, possibly a key piece of evidence.

Leap forward another 30 years: Officers investigating the Mora flats case today probably could have linked the slug to the rifle while still in the field, starting with calipers that reveal caliber size and continuing from there, said Brooks.

“Once you understand the size of the bullet and the twists and lands and grooves that a barrel gives off, you often can narrow down what killed the animal to a specific caliber and even a specific type of weapon – say, a .30 caliber rifle, probably a Winchester, Model 94,” he said. “For an exact match to use in court, we still need the lab. But we can get it close enough now that if there are three people in camp, one shooting a Model 94 and two shooting Remingtons, we can say to the guy with the Winchester, ‘We need to talk.’ “

Blood evidence, such as streaks on a tailgate or smears on a hunter’s coveralls, has long been a clue that an animal has been killed. But neither a ’40s nor ’70s-era game warden could prove that a blood sample was from an elk, say, or a deer.

By the mid-70s, “The crime lab could tell us if it was non-human. That was it,” said Jim Vaught, former chief of the Law Enforcement Division.

“Now labs can match blood samples to a specific species living in a specific area of the country and, when needed, match it to a specific animal,” said Brian Gleadle, assistant chief of the Law Enforcement Division.

Hairball buddies and cell phones

Dan Pursley, Operation Game Thief‘s first coordinator when the cash-for-calls program started in June 1977, said the latter situation fit his experience. The tip from Mora Flats was something of an exception, however, as he and Vaught proved in an extraordinary research project in the early 1970s.

Using an undercover agent, they knocked the naivete out of agency and public perceptions about New Mexicans’ attitudes toward poaching and their willingness to report it.

The agent collected discarded heads, hides and legs of legally taken animals during season, froze them for later use, then planted them to appear as poaching evidence – much like the evidence reported by the Mora Flats tipster. Under permit, he also killed a small number of animals out of season. The statistical aim was to compare citizen and officer reports of apparent violations with the known fakes, then estimate a violation rate.

Therein lay the problem: The agent recorded 43 times when he knew someone had seen him “poaching.” He was turned in once, by someone who mistakenly thought he was butchering a calf. Hardly any of his simulations came to light. He did not get caught.

“The bottom line was that no matter how many violations you made obvious to the public, they wouldn’t report the SOBs,” Pursley recalled. “That was the revelation. That was the part that set everybody back on their ear.”

The statistical results also shocked the system, indicating 34,000 deer and 3,000 antelope per year went to illegal kills – numbers the agency, press and public seized upon. In retrospect, however, the number of reports was so low the numbers were questionable.

“It skewed the data,” Pursley said. “What we really had was a public relations opportunity, and that’s where we had to go with it.”

The agency went to Operation Game Thief. New Mexico became the first state in the nation to set up a hotline and offer cash – donated by sportsmen – for anonymous tips.

“We gave the good guys a way to help, by sending money. The good guys may want to help with information, but usually they don’t have much: the guys who try to follow the rules don’t hunt with the hairballs. One helluva lot of people I paid rewards to were the poachers’ hairball buddies – or their angry girlfriends and exwives,” he said.

A victimless crime

Technology, though, is changing that, said Dan Brooks. The ubiquitous cell phone enables people in the field to call in violations on the spot, and people even can send information on the internet.

“Operation Game Thief still proves to be a valuable tool today,” said Brooks. “Poaching is a victimless crime, in the sense that there’s no way a deer or elk can report a violation. The best conduit we can provide is that 800 number. People still call and provide information, restarting cases that have been stalled for months.”

The research study led to Operation Game Thief and generated huge amounts of publicity, but did it alter attitudes?

“To a certain extent it did improve the situation,” said Vaught. “It may have dried up some of that poaching. It certainly brought focus to it and driedup some of that 19305 ‘It’s okay if you’re feeding your family’ kind of thing,” he said.

Another effect: The Legislature increased statutory penalties for game law violations and many magistrates seemed inclined to impose them. The average fine in fiscal year 1977-78 was $76, nearly doubling the ’76-77 average of $40. Fines in Operation Game Thief prosecutions – many for big game violations-averaged nearly $150.

Nonetheless, magistrates in some jurisdictions continued to dismiss charges or levy nominal fines, especially against local violators, Vaught observed.

Another emotionally loaded event, the 1990 murder of Lindrith rancher Freeman Lee Davis during a confrontation with a suspected spot-lighter, prompted outraged legislators to establish an effective deterrent that bypassed the magistrate courts.

Starting in 1991, the game department could confiscate and auction off vehicles used for spotlighting – hunting big game with an artificial light – provided the vehicle’s owner knew of that use. Spotlighting penalties also included revocation of hunting and fishing license privileges for up to three years, confiscation of firearms or bows and civil damage assessments for the state’s loss of wildlife, in addition to court fines and fees.

Decoys and danger

Stiff penalties were half the deterrent formula. The other part involved the chances of getting caught. That also changed, particularly for hunting by artificial light. In 1989 the Department tested the use of artificial deer and elk to catch violators. Poachers chose to shoot at the fake game animal, staked out by officers, while hunters and passersby did not.

Gleadle tracked the changes. In 1988, officers issued 60 citations for hunting with the aid of artificial lights – a result of intensive, ongoing and expensive statewide efforts using aircraft and multiple teams of officers on the ground.

1n 1989, the first year of decoy use, officers issued 81 citations as violators started coming to the officers. In 1990, as officers perfected and expanded the use of decoys and began to confiscate vehicles, they wrote 174 – a peak year. They wrote 130 the following year and agency spokesmen continued to publicize widely the efficacy of decoys and the painful loss of favored pickups.

The combination, as with Operation Game Thief, worked. By 1999, there were only 16 cases of hunting with the aid of spotlights and headlights – the lowest ever, although such cases were up to 35 in 2001. With recent changes in seizure and forfeiture laws affecting all law enforcement agencies, that highly effective deterrent has, in practical terms, been lost.

Decoy use, however, expanded to daylight hours in the fall of 2003, thanks to Sen. Tim Jennings and his efforts to pass the artificial wildlife bill, in an attempt to curb the dangerous practice of hunting and shooting from vehicles on roads or highways. As at nighttime operations. officers stake out the fake deer and elk in teams. However, officers often work alone in very remote areas with assistance sometimes hours away.

A double murder

State Game Warden Gilbert C. de Baca observed in 1914, recording the hardships his deputies faced, “These are not all of the warden’s troubles. He must often face criminal poachers, heavily armed, who will take advantage of him, if he is not careful, and shoot him down.”

Fortunately, that has not happened in New Mexioo.

“We’ve just been lucky,” said John Miles former Law Enforcement chief, reiterating the words of numerous other experienced officers.

Miles started out as a conservation officer in Reserve, then Pecos. A poaching suspect in a remote Pecos Wilderness elk camp fired a shot that struck a tree above Miles’ head. In another case, he broke a shotgun stock across a suspect’s jaw to defend himself. That case involved no game laws; he was assisting a State Police officer. As is often the case in small communities, the game warden and State Police officer depend on one another.

“It’s very common for them to help each other, actually,” said Brooks. “When it comes to these outlying areas, our backup is State Police and we’re the State Police backup, as state employees and state officers.

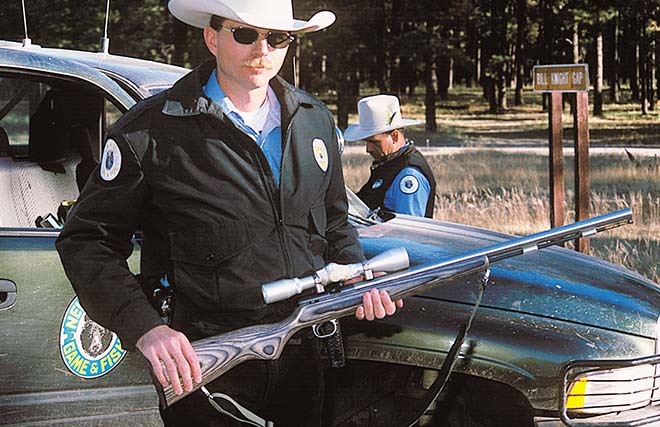

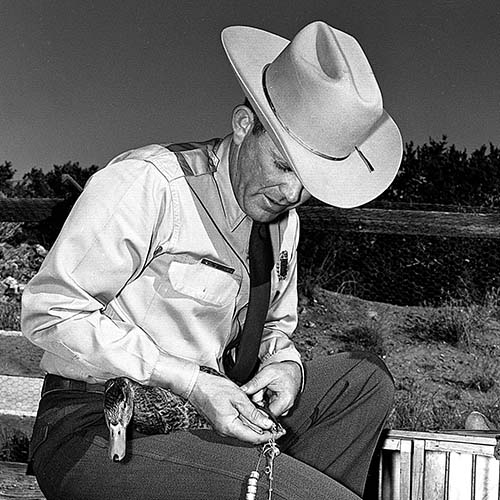

Photo: Martin Frentzel.

A number of New Mexico game officers also have been beaten up, cut, and threatened with guns and gunfire. There are other dangers, of course-icy roads, jittery horses, careless gun handlers, simple exhaustion but to date there have been no life-threatening injuries or fatalities related to wildlife law enforcement in New Mexioo.

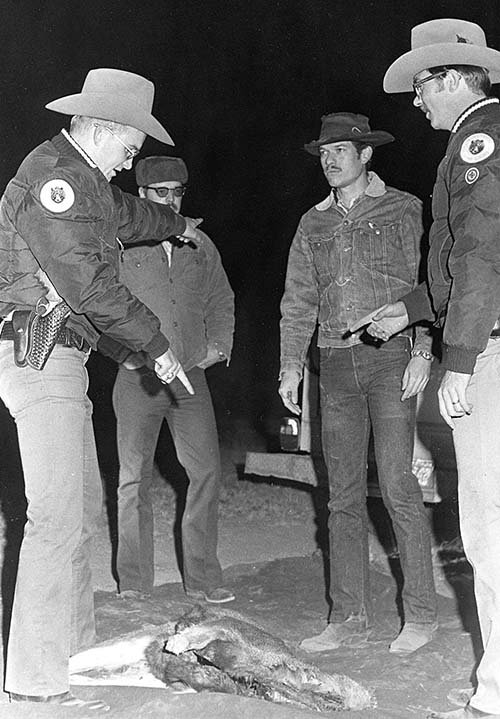

Not all states are so lucky. The 1981 double murder of Idaho reservation officers Bill Pogue and Conley Elms was particularly unsettling.

Claude Dallas, now-imprisoned for murder, pulled a hidden pistol and shot the wardens down when they caught him with illegal deer meat and bobcat hides in his camp. He then finished them off with .22 bullets behind the ears. The brutality gave officers cold chills. Some locals and news media continue to lionize Dallas as a mountain man folk hero-deeply angering the small fraternity of wildlife officers.

Reactive control model

Training helps keep our wildlife officers’ thin thread of luck from running out, and New Mexico’s training has evolved along with other enforcement agencies.

In 1948 Bill Huey’s supervisor assigned him as game warden in Reserve. The approach to training at that time was consistent: there was none.

“They handed me a ticket book,” said Huey, who eventually became director.

By the early 1970s, game officers were required to attend a month-long school at the newly created New Mexico Law Enforcement Academy, plus a week of in service schooling in wildlife law enforcement.

The training includes class work in all the intricate legalities governing arrest, search and seizure, use of force, interrogations and juvenile justice, crime scene investigations, preservation of evidence and testifying in court. Trainees also drill on physical fitness, firearms, and personal defense.

Brooks said the training reduces the rate of assaults. Today’s officers have more options than their predecessors had, including pepper spray and batons – intermediate options between fisticuffs and deadly force.

“We’ve moved to the reactive control model the Department of Public Safety uses and teaches,” said Brooks. “It tells you when you can use force and at what level you can use it. As a person becomes noncompliant, uncooperative, fails to follow verbal commands or even becomes combative, we understand what level of force we can use so it never gets to an out-and-out assault. The idea is to stop the action.”

Brooks said there were 43 officers and their district supervisors on the ground in September 2003, a few vacant districts and close to 20 commissioned officers in area offices.

That’s far more than the 13 district officers and half-dozen patrolmen Elliott Barker had in fiscal year 1949- 1950 – the same year Barker created the position of Law Enforcement Division chief that Brooks now holds. But nonexistent training standards and virtually nil liability risks allowed Barker far more leeway to commission law officers.

“Of course, all regular employees of the Department, regardless of what type of work they may be doing, hold deputy game warden commissions and do their part in law enforcement work,” Barker wrote in the mid-40s.

That practice continued for several decades, but liability risks, training requirements and demands of regular work swamped it. Barker’s 20-man force of full-time officers plus part-time assistants patrolled a state with a 1950 population of 681,000, about 48,000 big game license buyers and 64,000 fishing license holders. Barker’s crew prosecuted 595 cases.

The 2000 census takers counted 1.8 million New Mexicans. Nearly 112,000 people bought one or more hunting licenses in fiscal year 2000-2001, and 227,000 bought fishing licenses. The 4045 district officers made 77,000 field contacts and wrote 3,200 citations, including nearly 1,200 who were fishing without a license.

So law enforcement, unlike extensive refuge systems and intensive, statewide predator control, has maintained a place in wildlife management.

“We can show clearly, on an annual basis, that about 93 percent of the license buying hunters and anglers are in compliance with our laws and playing by the rules,” said Brooks. “About seven percent, plus or minus, are not and have the ability to affect the resource drastically.”

By the truckload

Pickens’ Mora Flats case and a recently solved case of commercial killings had one thing in common: tips from the public.

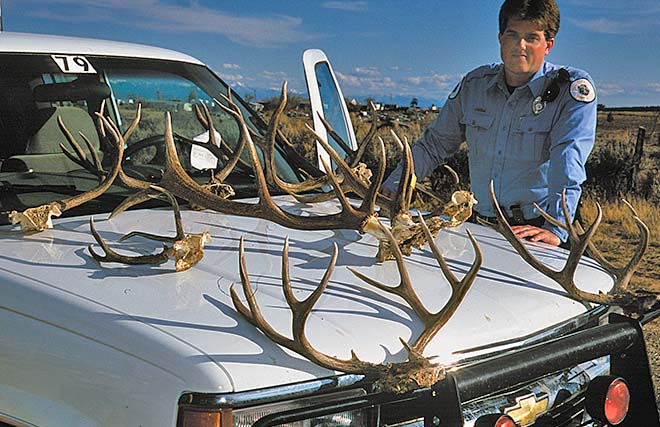

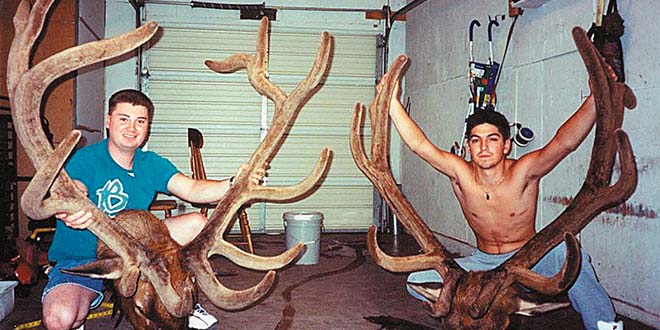

In 1999, numerous anonymous callers gave the Department the same tip – a man from Las Vegas was poaching not just once a year, but repeatedly. One caller said the man was poaching and selling antlers by the “truckload.” Tips and evidence put officers on the trail of Zach Romero and his associates, following a series of poachings in northeastern New Mexico in which bull elk were found shot with only the heads removed.

Firearms examination and DNA testing linked Romero and Calvin Parsons to one of these beheaded elk – its antlers still in velvet – found July 1999 east of Raton. Samples taken from the elk carcass matched both DNA from one of the velvet antlers seized during a search warrant of Romero’s home and bloodstains found in Parson’s van. Crime lab tests determined that a cartridge casing found at the crime scene was fired from the same rifle as cartridge casings found at Parson’s house. Officers also determined that Romero was selling antlers to buyers in three different states.

In January 2003, Romero pleaded guilty to two felonies and 10 misdemeanors related to the case. He currently is paying $12,000 in fines and civil damages in a plea agreement with the state. He forfeited his .300 Weatherby rifle and numerous heads and antlers seized during the search.

Calvin Parsons was found guilty of transponation of stolen livestock/game and conspiracy to commit felony transponation, both fourth-degree felonies. He was fined $5,000, wore an ankle bracelet for 45 days and will serve 7. 75 months of the 18-month sentence in the State Penitentiary. Judge Sam Sanchez of the Eighth Judicial District Court presided in the case. The conviction currently is being appealed by the defendant in the Court of Appeals.

Parsons commented to some that he thought his sentence was extreme, considering it was not a murder charge.

“For some people poaching, or stealing the state’s wildlife, is not considered a very serious crime,” said Gleadle.

Officers from New Mexico State Police, Colorado Division of Wildlife, Wyoming Game and Fish Crime Lab and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Crime Lab helped the Department assemble more than 1,000 pages of documents. That effort led to the collection and seizure of more than 40 illegally possessed game animals in this single related case. A case of this magnitude required tremendous coordination and effort by Assistant District Attorney Leslie Fernandez and her staff from the Eighth Judicial District. The combined efforts by officers and legal staff led to convictions of the two men.

“The conviction and sentence were good for New Mexico’s wildlife,” said Jim Comins, principle investigator for case.

“There still are people out there abusing the resource,” said Brooks, “and there’s still a need for good law enforcement – patrolling, checking – ultimately for two things: conservation of the resource so it will be here in the future, and the sharing and wise use of that resource. There’s always going to be that need for officers in the field.”

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations