New Mexico Wildlife (Winter 2003, Vol 48 Num 4)

Making tracks: a century of wildlife management, part 5 of 9

Culture clash: early law enforcement efforts encounter dissent

By John Crenshaw

Former Public Affairs chief, New Mexico Wildlife editor, and game warden, retired in 1997.

New Mexico’s first territorial game warden was appointed in 1903. There was no school of wildlife management, no state fish hatchery system and few, if any, Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep and elk.

The Department of Game and Fish has grown out of that first appointment to an agency authorized to employ 286.5 individuals. Their mission is to provide the people of New Mexico with a flexible system of fish and wildlife management that perpetuates the state’s vast wealth of wildlife species.

During the last century of challenge, the agency has restored elk – too well in some minds; put Bighorn sheep back on the mountains; constructed and reconstructed six fish hatcheries with a seventh in the works. Along the trail the Department has assumed new responsibilities as the public’s desire to retain its wildlife heritage embraced species once believed less than desirable.

With this 9-part series “A Century of Wildlife Management” from New Mexico Wildlife, we look at the tracks this outfit made during its first century. Those tracks lead to the highest peak, and to the hottest desert, anywhere wildlife might need a helping hand.

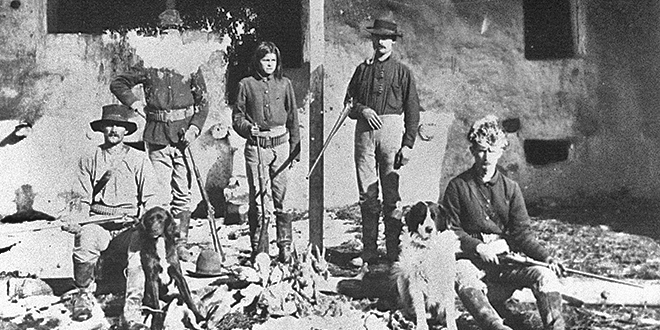

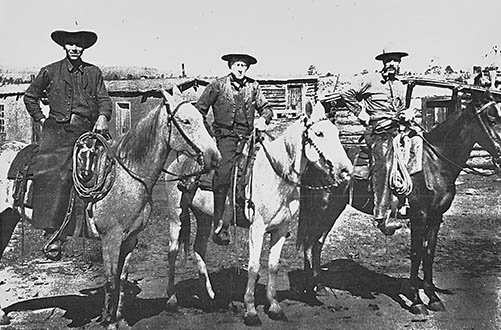

Above: Nutria Village hunting party, Zuni Pueblo circa 1890. Photo: Christian Barthelmess, Museum of New Mexico, Neg. No. 86929.

Culture Clash: Early law enforcement efforts encounter dissent

When alarming drops in wildlife populations inspired the conservation movement in the late 1800s, people trying to fix the problem had few tools. New Mexico followed the pattern of the times, seizing upon predator control, enforcing restraints on hunting and fishing, and following up with an extensive system of refuges.

Of that original triad, only law enforcement survives. But paying bounties on coyotes was easier and more widely accepted than enforcing closed seasons and bag limits on deer.

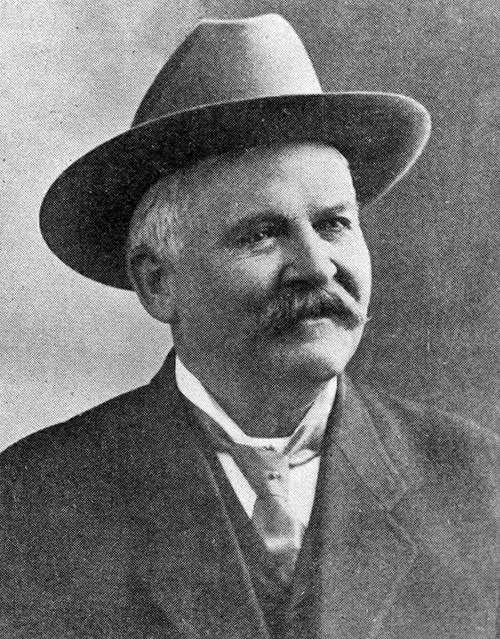

The officers wearing the blue uniforms of today’s Game and Fish Department face entirely new problems and some startlingly similar to those of their predecessors. However, they have history, science, technology, education, training and public support that Page Otero, first Territorial Game Warden, did not.

Appointed in 1903 to enforce the nascent game laws, Otero took on a monumental task with few resources against widespread resistance. Limits on hunting arid fishing were primarily a movement by upper-class Anglo and Hispanic leaders such as Otero himself, brother to the governor and scion of a moneyed, politically powerful family. Urbanized, mostly Anglo sportsmen and large landholders added impetus. This new conservation ethic ran headlong into existing subsistence uses of New Mexican Indians, rural Hispanics and newly resident Anglo pioneers.

Ripe for violence

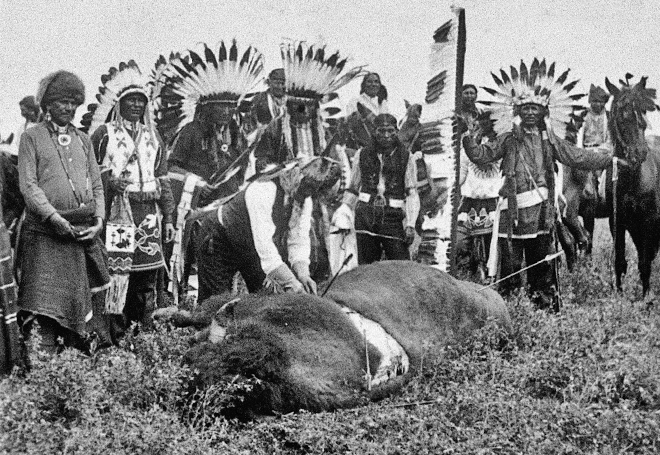

Indigenous peoples’ hunting practices in particular were steeped in centuries-old cultural and religious customs. Communal forays by numerous hunters, sharing a collective goal of laying in substantial meat supplies for the village, fit poorly with fledgling game laws that stood on closed seasons and bag limits such as one buck deer per hunter per year.

“Game laws like these indicated differences in how Indians and conservationists thought about wildlife abundance,” wrote University of San Diego history professor Louis Warren in his book, The Hunter’s Game. “For Indian hunters, game would appear if hunters behaved properly and propitiated the spirits; to conservationists, game would become abundant only if state or territorial authorities controlled access to the hunting grounds and limited the take.”

The conflicts were serious, ripe for violence. Further, Indian hunting offered easy explanations for dwindling game herds of game.

“The slaughter of deer by the Apache, Navajo and Pueblo Indian tribes who make their raids from their reservations each fall (and at other times) has done more than all other agencies combined to reduce the number of deer and antelope herds,” Otero wrote in his reports of 1903 and 1904.

Otero’s comment reflected a near-universal view, overlooking impacts from Anglos and Hispanos own market and subsistence hunting and ignoring domestic livestock’s impacts on wildlife habitat.

Conflict and contraband

On the receiving end of angry, sometimes fearful, complaints about Indian party hunters, especially in the Mogollon Mountains and Plains of San Augustin, Otero had more than he could deal with as a one-person agency. He called for assistance in 1905 from the 11-man New Mexico Mounted Police – forerunner to the State Police.

Warren writes that Lt. Cipriano Baca apprehended a group from San Felipe Pueblo with four doe hides, but Baca and a companion backed away from a serious confrontation arresting the suspects later at the pueblo. Baca reported that to have made arrests in the field, “He would have to kill some of them.”

Mounted Patrol Capt. John Fullerton conceded his force could do little, estimating that more than 150 Indians from several tribes were hunting across the area. Frustrated and impotent, Otero sought help from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and its agents on the pueblos and reservations, but received little.

A successor Territorial Game Warden, Thomas Gable, reported in 1911 that “Up to two years ago nothing had ever been accomplished in the way of putting a stop to the reckless, wholesale slaughter of deer and all big game by the reservation and Pueblo Indians. They simply killed at will, in accordance with their long established and unmolested custom.”

Gable’s deputies intercepted five parties of Indian hunters, making arrests and seizing contraband, among them a party 27 Laguna Indians:

“One band of Pueblo Indians arrested in the Datil Mountains by Deputy Bob Lewis and Earl Morley had in their possession nearly a hundred of deer – bucks, does, and fawns. The groups was fined $500.00 and $125.00 costs, which they paid,” Gable wrote.

An influx of aliens

To help stem the tide, Gable wrote, “l had printed several thousand copies of the law, in English and Spanish; also a synopsis on cards and cloth posters, sending them to all the county clerks, deputy game wardens, forest supervisors and guards, teachers at the various Indian pueblos and reservations, as well as to individuals and newspapers of the territory.”

Combined enforcement and information campaigns paid off: ” … during the year 1911, I have had no complaint of the wholesale slaughter of deer. .. and I anticipate no further violations of the game law on the part of the Indians.”

Contemporary biases extended beyond Native Americans. A 1921 law forbidding Indians from carrying firearms off their reservations also forbade foreign-born, un-naturalized residents of New Mexico or adjoining states to hunt or take any game or to possess a shotgn or rifle.

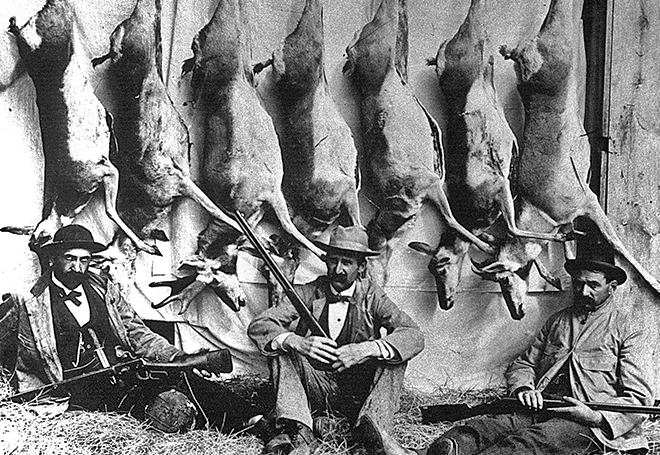

Photo: NMDGF.

“The need for this was the influx of aliens to the coal mining operations at Raton, Dawson, Cerrillos and Gallup. Such aliens reportedly had no respect for game laws,” wrote long-time State Game Warden Elliott Barker in an unpublished history of the agency. Many of the newcomers were Italian. Times change. A Dawson miner’s descendant, Gerald Maracchini, became director of the Game and Fish Department in the 1990s. Peter Pino, of Zia Pueblo, is now a member of the State Game Commission.

Gable’s 1911 report also made a point “that the native people, comprising those of Mexican descent, have been consistent observers of the game laws, and it has become a generally recognized fact, among them, as among all others, that the protection of game and fish is both necessary and beneficial…”

Gable listed some 300 volunteer deputies and recorded 107 arrests, 99 convictions, six acquittals and two pending cases as his nearly three years in office ended. He probably dealt with about 7,000 licensed hunters. Resident trout fishing licenses were not required, so there is no viable estimate of angler numbers.

Blinds and salt licks

The territory became a state in 1912, and Trinidad C de Baca took office as State Game Warden. In his biannual report of 1914 he wrote of improving compliance by Indians, with a caveat. “In nearly every case now the Indians are supplied with proper hunting licenses, but they must be constantly watched as they hunt and kill out of season and exceed the limit where they have the chance.”

C de Baca observed that support from other groups was also weak:

“It is hard to secure evidence from farmers or pioneers in sparsely settled districts. These people do not like to testify in court against an offender for fear their property will be damaged … In many instances the settlers are opposed to game laws in general and sympathize with the poachers,” he wrote.

Those attitudes fueled frustrations among the growing fraternity of New Mexico sportsmen, fertile ground for the organizational skills of noted wildlife ecologist Aldo Leopold, at the time a U.S. Forest Service recreation officer in Albuquerque.

A childhood memory of the late Larry Sandoval, reared in Wagon Mound, illustrates that not all Hispanic subsistence hunters fit Warden Gable’s assessments or bought into the sportsman model Leopold embraced.

“My uncle took me up around Ocate when I was about seven, and we hid in a blind over some salt there and waited for deer. We didn’t get one and he didn’t take me when he went back-he said l couldn’t hold still. But that was how he did it,” Sandoval related.

That was about 1917; shooting deer from blinds and over salt licks had been illegal for years, and State Game Warden Theodore Rouault arrested a pair of Las Vegas men for doing that very thing that year.

Leopold scorched the duo, as quoted in Curt Meine’s biography, “Aldo Leopold, His Life and Work.”

“What marvelous skill it took to pot her, from a dead rest, at fifty yards! What elemental pride must have stirred in their breasts, when they removed her mangy summer hide, and heard her orphan fawn bleating hungrily nearby!” Leopold exploded.

No pay, no glory

As a Forest Service employee, Leopold was a deputy game warden. He took his enforcement duties seriously.

In October, 1915, he led the organizational meeting of the Albuquerque GPA. Among the minutes preserved by the Albuquerque Wildlife Federation, its successor, was a list of assignments for members to patrol during waterfowl season along the Rio Grande. Leopold took the stretch where Tingley Beach is now.

He was active elsewhere. Shortly after helping organize Albuquerque sportsmen, he went to Taos to help start a club there.

The day after organizing in Taos, Leopold teamed with future warden Barker (then Carson Forest Supervisor) to set an example by investigating an illegal deer kill. “Within twenty-four hours, the offenders were arrested, tried, convicted and fined,” Meine wrote.

At the time, all Forest Service rangers .and supervisors were deputized – Warden C de Baca listed nearly 100 of them statewide in 1914 – and acted as a deterrent to poaching on public lands.

C de Baca praised the foresters’ work, wishing they could do even more, noting that his mostly volunteer deputies often were criticized.

“The sportsman may sit in his comfortable home and complain … but if this same sportsman undertook to enforce the laws he might have a different story…,” C de Baca wrote in 1914.

“In the first place game wardens are the poorest paid officers in the country, and in the second place they are seldom given sufficient powers and support to enforce the laws and protect themselves. At least three-quarters of the wardens receive no pay whatever, and yet their work is decidedly of the most difficult and strenuous character. There is no glory in the service, either, and all that a successful warden generally receives is criticism and abuse. If he is slow and timid he is ridiculed. If he enforces the law rigidly he is abused,” C de Baca wrote.

Excess of leniency

The first State Game Warden recorded some observations on the criminal justice system as well, noting that “on the whole, the record is gratifying,” and that prosecuting attorneys “have generally shown commendable zeal.”

However, he went on, “Justices of the peace… have been inclined to exercise an excess of leniency, even going so far in some cases as to disregard the law in the imposition of penalties less than the minimum provided. Seldom is a fine, in excess of the minimum imposed.”

Those suspended fines were also a disincentive to the voluntary wardens, who were paid half of the fines assessed. Eventually, the pitfalls of paying enforcement officers with fine money were recognized, and the fines went into the Game Protection Fund for a few years. By 1945, the legislature directed that fines from wildlife law violations go to the state’s school fund, negating any defendants’ claim the agency picked on him just to get the money.

But fines are deterrents, and, as C de Baca concluded, “If the maximum punishment was imposed in a few instances, I believe there would be less work for the courts.”

C de Baca wanted to hire five full-time deputies and station them in districts around the state, but a 1912 legislative directive shifting $8,000 of the $8,727.28 balance from the infant Game Protection Fund to the State Salary Fund stymied him. He hardly had funds to print the game laws.

“Of course, under these conditions … employment of wardens under salary had to be abandoned … In two or three instances I have been able to keep men employed, especially during the open season for about three months, and have at times employed deputies to attend to special cases,” he wrote.

Sportsmen objected to the financial raids, and by 1921 got statutory protection for the Game Protection Fund. In the meantime, C de Baca’s successors continued fielding unpaid volunteers, hiring part-time special deputies and, eventually, recruiting full-time, salaried officers.

State Game Warden Edgar Perry wrote in his biannual report for fiscal years I 928-I 930, ” … we have the state divided into six districts, each in charge of a competent district deputy … the districts are necessarily very large, and one man could not hope to even approximately enforce the game laws upon them by his own efforts alone.”

A sacrifice of time

In fiscal 1928-29, those half-dozen field officers were dealing with about 31,800 licensees: 3,200 bought combination hunting-fishing licenses, 14,800 bought hunting licenses, and 18,800 bought fishing licenses.

For help, the agency hired 40 temporary patrol officers to serve in congested hunting areas, Perry wrote, and each district officer also recruited volunteer deputies.

“We select men who are influential in their communities,” he wrote, “and the mere fact that these men have publicly taken up the cudgels in defense of game law enforcement is alone sufficient to deter many prospective violators.”

Perry’s volunteers made relatively few arrests, “but by far the greater part of our prosecutions are based upon information furnished by them.”

His two-year total of charges brought: The paid deputies won 159 cases and lost 19; forest officers won 31 and lost one, voluntary deputies won 53 and lost 16.

He expressed a conviction that those numbers represented “…fewer game law violations per unit of population than probably any other state in the union.”

He attributed that not only to earnest patrol work but deputies’ constant educational campaigns in their districts.

“We do all of it that is possible with our limited means… our field men are working constantly with boy scouts, schools, civic organizations and the game protective associations… This necessarily involves a sacrifice of a good deal of time that might otherwise be devoted to strictly patrol work, but I personally believe it to be a good investment…”

As Perry’s numbers indicate, game law cases have always had a very high conviction rate, because the officer usually observes the violation in person: She checks an angler who has no license, or finds an untagged elk in the hunter’s camp.

But some cases are not so cut and dried: investigations -sometimes long-term – are necessary to bring a violator into the court system.

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations