New Mexico Wildlife (Summer 2003, Vol 48 Num 2)

Making tracks: a century of wildlife management, part 4 of 9

Turf wars: sportsmen struggle to sustain wildlife management over politics

By John Crenshaw

Former Public Affairs chief, New Mexico Wildlife editor, and game warden, retired in 1997.

New Mexico’s first territorial game warden was appointed in 1903. There was no school of wildlife management, no state fish hatchery system and few, if any, Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep and elk.

The Department of Game and Fish has grown out of that first appointment to an agency authorized to employ 286.5 individuals. Their mission is to provide the people of New Mexico with a flexible system of fish and wildlife management that perpetuates the state’s vast wealth of wildlife species.

During the last century of challenge, the agency has restored elk – too well in some minds; put Bighorn sheep back on the mountains; constructed and reconstructed six fish hatcheries with a seventh in the works. Along the trail the Department has assumed new responsibilities as the public’s desire to retain its wildlife heritage embraced species once believed less than desirable.

With this 9-part series “A Century of Wildlife Management” from New Mexico Wildlife, we look at the tracks this outfit made during its first century. Those tracks lead to the highest peak, and to the hottest desert, anywhere wildlife might need a helping hand.

Above: An early hatchery building. Photo: NMDGF.

Turf wars: sportsmen struggle to sustain wildlife management over politics

The governor said he couldn’t sign the bill because he had promised one Thomas Delgado the position, “and I positively won’t break a campaign promise.”

Neblett, as Commission chairman, made his own promise: The Commission would appoint Tom Delgado if Hannett would sign the bill. It solved the problem. Hannett signed. The bill was law.

The maneuvering wasn’t over yet. Neblett persuaded Delgado – another appointee who knew nothing of game management – to hire a well-qualified executive secretary to handle the details. “Delgado readily agreed,” wrote former State Game Commissioner Elliott Barker. The executive secretary would gain valuable experience and be the prime candidate when Delgado’s two-year term expired.

Barker’s name came up again, but he was deeply involved in his family ranch and declined the offer. He recommended Edgar Perry, then a Forest Service ranger.

“Perry had become deeply interested in wildlife conservation, was a member of the GPA (Game Protection Association) and read up on wildlife management,” Barker wrote. “They then conferred with him, checked his forest ranger record and gave him the job.”

Amicable relations

In spite of some members’ feelings toward her, the GPA found Grace Melaven receptive to some of its ideas. So was Delgado. He met with the state association, now representing 26 chapters, and wrote in his annual report that “many matters were threshed out between the Department and Sportsmen, and a number of recommendations made by the latter were adopted by the Department and made a part of its plan. They were accepted in perfect good faith and have been followed to the best of the Department’s ability.”

Delgado’s tenure ended and the commission predictably appointed Edgar Perry as State Game Warden in January 1927, with the blessings of the association.

He, too, worked well with the sportsmen.

“Probably no where else on the continent do more amicable relations exist between sportsmen and conservation officials than in this state,” wrote Perry in his 1930 report. There were 41 chapters and nearly 7,000 members statewide and the Department recognized “that it belongs to the sportsmen as a plain matter of justice.”

“In most sections of the state today the Commission does not move in any important matter except with the advice of the local association,” Perry said. “A great many grievous errors have been avoided by pursing this policy, and it is seldom indeed that the opinion of the local sportsmen is not well grounded. Each year at its annual convention, the New Mexico G.P.A. harmonizes all sectional ideas and preferences and lays down broad general policies for the guidance of the Department. The Commission and other officials of the Department sit in on these conventions and take part in the discussions, and the Department thereafter feels bound to put into effect the policies just arrived at.”

Eye on the prize

While helping shape the Commission’s actions on refuges, predator control and law enforcement, and trying to influence hunting and fishing regulations set by the legislature, the state group kept its eye on the prize: vesting regulatory authority in the State Game Commission. Learning from its successes, the association drafted a comprehensive code well in advance of the legislative session.

“GPA clubs throughout the State worked hard prior to the 1929 Legislature to get senators and representatives to agree to support the bill. They thought they had it made, but unforeseen opposition developed.”

The bill died, one vote shy of passage.

Perry, in the 1930 report, wrote regretfully of that demise:

” …it becomes ever more obvious that under our tremendous variety of environmental conditions it (game) cannot be effectively managed on the basis of statewide prescriptions… the managing agency must have wide administrative latitude.”

He hoped the next Legislature would “be able to see the advantage of modernizing the principles of administering one of the state’s most valuable economic assets.”

It did, but with fallout for Perry, the commission and the associations that he could not have anticipated. “When the 1931 legislature met, a perfect regulatory bill was introduced, promptly passed, and was signed by Governor (Arthur) Seligman,” Barker wrote.

The law, praised at the national level, became a model for other states. Many sportsmen assumed the bill’s passage assured stability, Barker wrote – meaning the current commissioners and Warden Perry all would stay on board. Seligman and Neblett opted to clean house.

“They were shocked when Governor Seligman said that with the new law he thought we should start out with a new Commission, and he promptly appointed Judge Colin Neblett to be Chairman.”

The other two new members were Gilberto Espinosa, an Albuquerque attorney, and James McGhee, a Roswell attorney who later became a district judge.

Rumors ran rife that the new commission would oust Perry.

Neblett interviewed Barker for the warden’s job, confirming that Perry was on his way out. The judge confided that Perry had failed to resist political pressures, particularly by placing fish hatcheries in unproductive spots, and had manipulated his title-with cooperation from the former commission – to draw a higher salary. The commission had paid Perry $4,000 per year as executive secretary and named him “acting” warden, according to Barker, circumventing the legislatively fixed $3,000 salary of the state game warden.

A rocky start

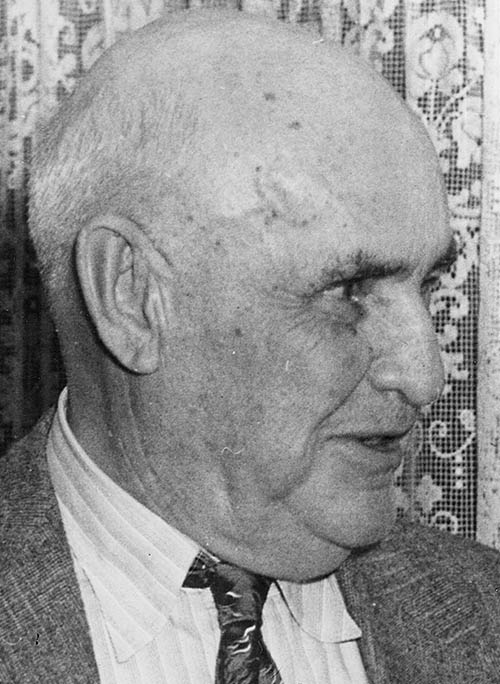

Barker at last got the job, starting April 1, 1931. He would keep it for 22 years, retiring in 1953.

The start was a bit rocky, he wrote in 1983:

“…in thinking over the happenings of the first three or four years of my tenure as State Game Warden there were serious conflicts with the GPA that no one else today knows much about.”

Among the conflicts were closing the unproductive hatcheries at Ruidoso and Chama that had plagued Warden Perry, and the state’s first antlerless deer hunt – in an era when shooting a doe was sacrilege – in the severely overpopulated Black Canyon area of the Gila National Forest.

“Some never got over E. L. Perry being relieved as State Game Warden,” Barker wrote.

One of the angriest was Dr. Fred Pettit, close friend and hunting companion of Leopold. He was a founder of both the state organization and its Albuquerque chapter.

Reacting to legislative maneuverings as Neblett shaped the stage for a new commission and warden, Pettit wrote to the president of the Eddy County chapter, Guy Reed, in February 1931:

“…I withdraw my suggestion that we carry the olive branch to Judge Neblett and try for a realignment of all the forces fighting for improved game conditions afield… I helped to create this Commission, in a sense I feel it is my own, and l shall fight to protect it… I think he is absolutely wrong in attempting thru the Legislature to impugn the honesty or motives of the Game Department and at the same time imperil the work that it has taken our undivided efforts to accomplish.”

Pettit was hardly a crank; he had labored hard to get portions of Elephant Butte and McMillan reservoirs opened to public waterfowl hunting, and led a successful campaign to keep La Joya marshes from being drained. With his sportsmen peers, he had struggled more than 15 years to extract the State Game Warden’s position from partisan politics and to create a stable commission with meaningful authority. Now, at the height of the GPA’s success, he and other association leaders viewed the commission and warden dismissals as a betrayal.

The heat was on

Anger lingered, but eased over time as the commission stabilized – Neblett would be chairman for 14 more years – and Barker proved himself forthright, fair, and capable. He remained unswayed by partisan politics and that independence, ironically, stemmed in large part from the raw political power and prowess of the judge and his fellow commissioners, who demonstrated it within weeks of Barker’s appointment.

In May 1931, the new warden warned his commissioners that he was being pressured to hire a man as a political payoff. Plus, the governor and Democratic Party chairman were demanding that Barker and all of his employees ante up two percent of their pay to the party in power, the then-standard practice of both parties. Barker resisted the patronage and payoff. The heat was on.

The commissioners bee-lined to the governor’s office.

“Two hours later they returned and assured me that I would not be bothered any more. It seems that they had it hot and heavy with Governor Seligman, who was strong-willed himself, and at one point tendered their resignations. The Governor was too smart to accept them, and finally agreed to keep hands off and let the Commission manage the Department,” Barker later wrote.

Barker justifiably prided himself and the department for standing up to political shenanigans, basing hires and promotions on merit, applying the best game management principles of the time, and enforcing game laws without regard to individual political connections. But it’s reasonable to speculate that had Neblett, McGhee and Espinosa not had both the will and the power to back Barker right from the start, there would have been another clean sweep of commissioners and a more politically malleable warden at the helm.

Rattling the door

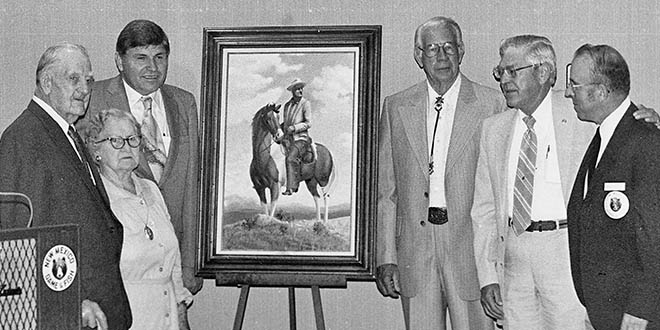

Although he kept his hand out of partisan elections, Barker had a gift for politics in the more general sense. He was well respected within national conservation circles, becoming president of both the Western and International Associations of Wildlife Agencies. Within New Mexico, he became quite a power in his own right.

“He was kind of a wildlife Steve Reynolds,” said Bill Huey, one of Barker’s successors, comparing Barker to the late state engineer. “What Steve Reynolds was to water, ESB was to wildlife.”

Barker wielded that considerable influence with the sportsmen’s groups, Huey recalled. “He kind of steered things.”

“Back in the late 40s and early 50s, the game protective associations had a chapter in damn near every town in the state,” said Huey. “It was a strong organization, and a lot of that strength was carried by pretty prominent citizens. They had enough weight to affect who was appointed to the State Game Commission. And when they wanted to talk to the governor, they went up there and rattled the door. They were admitted and paid attention to.”

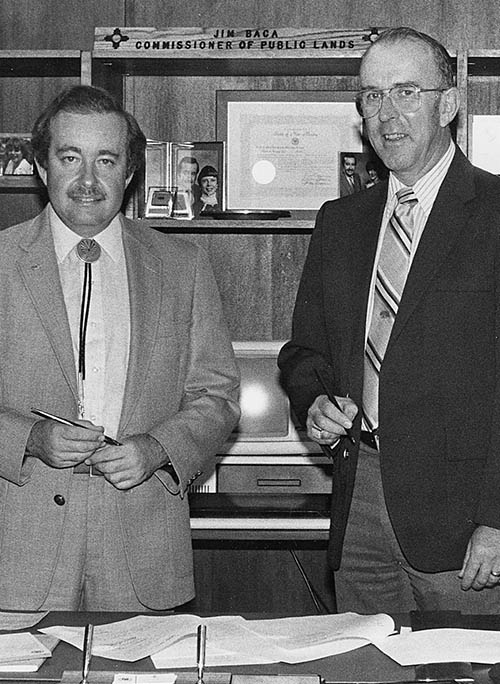

By the time Huey joined the agency in 1948, the GPAs focused on what the department was doing in terms of game and fish management. Huey, who started as a game warden and eventually became its director, made many a presentation to sportsmen’s groups.

“At the annual meetings, they would put the heat on the Department to justify our proposals,” Huey said. “It required you to look really carefully at the positions you took.”

Starting in the early 60s, the agency took its proposals on the road.

“We’d take everything we intended to do to the chapters to solidify what we were going to do with different seasons, dates, bag limits – management procedures,” Huey said.

The molasses of tradition

Legislative proposals also were brought to the sportsmen before they went to the Legislature.

“We put on quite a campaign to create the bond fund and an increase in the license fees that was passed to support the bond fund,” Huey said. “I think we talked to every organization in the state and made the pitch about what we’d do with the money if we got it, and how it would cost only a little bit.”

Although sportsmen lobbied a lot of legislation, they weren’t deeply involved in that piece, as Huey recalled.

“They didn’t object. That was the primary thing,” he said. “If they disagreed… everybody heard about it. That was one of the reasons it was important to contact them ahead of time and at least get them not to fight it.”

“Either-sex deer hunting was subject to a lot of controversy, a lot of discussion,” said Huey. “The length of the quail season was a big deal. And fishing seasons. I think the first of May was the opening on fishing season. Now it’s open year-round, and it’s considerably more appropriate to do it that way.”

Those first year-round trout seasons opened April 1, 1973.

David Weingarten, who in the late 1960s joined the Albuquerque chapter of what was then the state Wildlife Conservation Association, helped that change, slogging against the molasses of outdated tradition.

“I went before the game commission and argued, and now we have opportunities for year-round fishing for trout, even in the winter,” he said. “If your toes can stand it.”

One behind every stump

But sportsmen groups and members have long supported and set the example for ethical, reasonable behavior in the field, and something else was driving Weingarten on the issue.

“I became disappointed about TV coverage showing fist fights, among other things, on opening day,” Weingarten said. “The TV crews would show up with boats bumping into each other, people shouting, lines crossed. I thought that was a really negative vision of responsible hunting and fishing.”

He met both support and resistance within the agency.

“I learned that Harold Olson (fisheries biologist and eventually director) had come to the same conclusion,” Weingarten said. “But he wasn’t able to work it up through the department. I think Roy Barker (chief of fisheries in the 60s) had been the bottleneck,” he recalled.

Weingarten bumped up against Roy’s father, Elliott, on another issue-extending grouse season. Elliott was by then long retired from his job as State Game Warden but still steering, even though well into his 80s.

“There was just a one-week season,” Weingarten said. “I started investigating, writing other western states and asking Department people if the grouse population could stand a longer hunting season. Their response was supportive. One week was all Mr. Barker felt the grouse season should be. When we argued it at the Wildlife Federation, he said there used to be one behind every stump and they weren’t there any more. He thought there was a potential for overhunting.”

His background work paid off, though; the season is a month long, and grouse none the worse for it.

Following the tradition set by his GPA predecessors, Weingarten lobbied the Legislature on behalf of sportsmen’s groups. And not only about game animals, hunting and fishing.

“We were able to get the Share with Wildlife bill through,” he said, “the income tax refund check-off that supports a considerable amount of nongame and endangered species research.”

<h4>A twist of luck</h4>

He confesses to a twist of luck – a rookie legislator sponsored that bill.

“It didn’t have a lot of support, but it was one of those cases, I think, where they gave the junior member of the Legislature a bill,” he grinned.

“Another one we need to mention: Fred Gross was a legislator and worked on the Habitat Protection Act,” Weingarten said. “Fred was a member of the Wildlife Federation and was a major sponsor of that bill.”

That act authorizes the Commission, in concert with federal agencies, to close roads on federal lands to protect wildlife.

Not all their legislative work worked. One major effort was to change water laws to benefit streams and associated plants and wildlife.

“One of the disappointments was in-stream flow, which the Wildlife Federation and other conservation organizations attempted in the Legislature several times,” Weingarten recounted. “But we never got it through both houses. The acequia associations were concerned that it would be bad for their water rights. And Steve Reynolds spoke against it.”

Sometimes the object was to block what they saw as bad legislation.

“One that we killed in the 1980s was an attempt to start a wildlife ranching law, on open ranches,” he said.

The proposal echoed the Class A Park laws of the teens and 20s, which essentially gave ranchers ownership of all game within their property boundaries. It required no game-resistant fencing and allowed killing of intermingled wild and stocked game.

Sportsmen’s groups, with other environmental and conservation organizations, also helped kill a proposed paper mill on the Rio Grande near Albuquerque, a potential source of considerable stench and water pollution.

Fonner U.S. Senator Harrison Schmitt planted a seed during one of the state association’s annual meetings.

“One of the issues he brought up was: Should the sportsman contribute to the maintenance of wildlife habitat on public lands?” Weingarten said.

Apparently their answer was yes, and it shows up on hunting and fishing licenses as the $5 Habitat Improvement Stamp, authorized under the Sikes Act – a federal law allowing states to collect fees from hunters and anglers who use Bureau of Land Management or U.S. Forest Service lands. When it first came up in the late ’80s, the game department and commission asked for public input.

“Although many hunters and fishennen viewed this as an additional tax burden, the federation supported it,” Weingarten said. “I served on the first agency-public project committee. After a trial period, the commission extended the program. Again, many at the meeting objected, but the Wildlife Federation supported continuation.”

The money – now about $1 million a year-flows back to the federal agencies as a major funding source for on-the-ground enhancements of wildlife habitat, including controlled bums and watering units.

“In many cases, wildlife groups provided labor and the federal agencies found matching funds to support these projects,” Weingarten added.

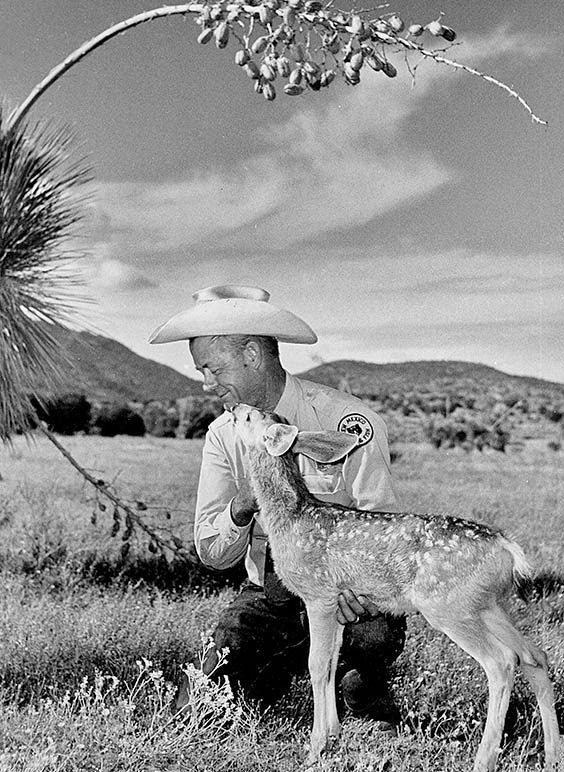

<h4>Sweat equity</h4>

Labor, indeed. Since their inception, wildlife groups have invested a huge amount of sweat equity in habitat projects, game captures and releases, game check stations and fish stocking. They’ve backpacked trout fry into the Rio Grande Gorge; boxed and fenced springs; laid pipe and installed troughs; picked and shoveled clay and sand; rolled rocks, planted trees, dug postholes, strung wire; wrestled large animals; built trick tanks and guzzlers; taught hunter education classes and ‘how-to’ clinics to beginners. The list is endless, it stretches across the 100- year history of the agency, and it’s statewide.

Sportsmen’s work on the Valle Vidal area is typical. “I think we’ve been going to Valle Vidal for at least 20 years, doing projects there: stream structures, willow plantings, fencing exclosures to asses the aspen growth; taking down old fencing,” Weingarten said. “Bill Zeedyk (a federation member and retired U.S. Forest Service employee) worked on meadows restoration. You block the stream some and spread the water out, then put rocks around – it’s wet marsh restoration.”

What drove him to give up personal time for the frequently frustrating and exhausting work as a volunteer legislative lobbyist, or pick up a shovel or fencing pliers and go to work? Maybe his modest answer speaks for the many hundreds who have volwlteered their own energy for wildlife.

“I got acquainted with Lany Merovka (formerly with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Albuquerque) through a mutual interest in crow hunting,” said Weingarten. “Larry was about 25 years older than I was, and was kind of my mentor. We went hunting and fishing together for at least 20 years. He enlisted me into the wildlife federation by saying, ‘Here you are taking advantage of all this wildlife. What are you going to do for it?'”

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations