New Mexico Wildlife (Summer 2003, Vol 48 Num 2)

Making tracks: a century of wildlife management, part 3 of 9

Profiles in conservation: Aldo Leopold and Elliott Barker provide legendary leadership

By John Crenshaw

Former Public Affairs chief, New Mexico Wildlife editor, and game warden, retired in 1997.

New Mexico’s first territorial game warden was appointed in 1903. There was no school of wildlife management, no state fish hatchery system and few, if any, Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep and elk.

The Department of Game and Fish has grown out of that first appointment to an agency authorized to employ 286.5 individuals. Their mission is to provide the people of New Mexico with a flexible system of fish and wildlife management that perpetuates the state’s vast wealth of wildlife species.

During the last century of challenge, the agency has restored elk – too well in some minds; put Bighorn sheep back on the mountains; constructed and reconstructed six fish hatcheries with a seventh in the works. Along the trail the Department has assumed new responsibilities as the public’s desire to retain its wildlife heritage embraced species once believed less than desirable.

With this 9-part series “A Century of Wildlife Management” from New Mexico Wildlife, we look at the tracks this outfit made during its first century. Those tracks lead to the highest peak, and to the hottest desert, anywhere wildlife might need a helping hand.

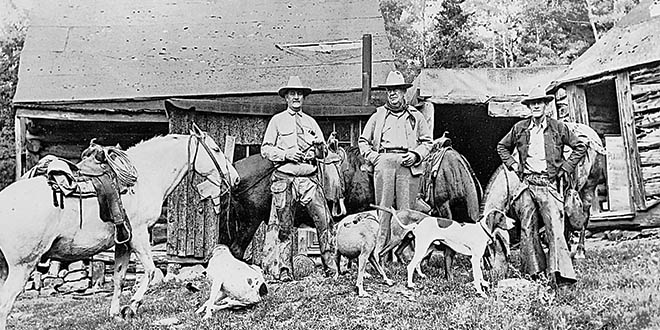

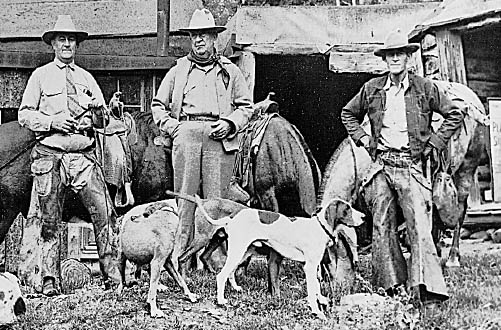

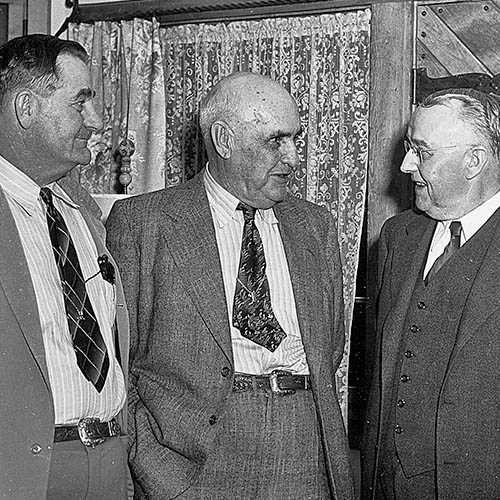

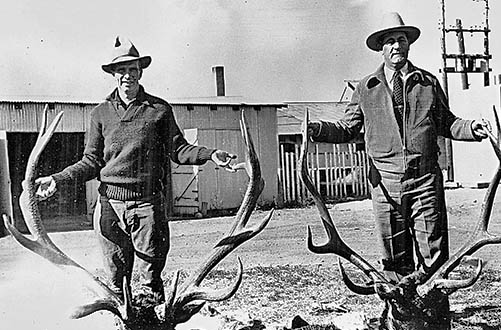

Above: Left to right, Elliott Barker, Gov. Mabry and Roy Snyder hunting lions. Photo: NMDGF.

Profiles in conservation: Aldo Leopold and Elliott Barker provide legendary leadership

“There were giants in the earth in those days … ” – Genesis 6:4

A heady brew of passion, power, politics and persistence – combined to create the Game and Fish Department much as it is today, and virtually all its history entwines with the history and actions of the sportsmen-conservationists, their Game Protective Associations and its successors.

New Mexico’s sportsmen’s movement mirrored national developments, but this state was particularly rich in strong personalities. Among the conservation pioneers who shaped legislation and steered public opinion were Mile Burford, a Silver City rancher who led the state’s first sportsmen’s association; territorial legislator, state and federal judge Colin Neblett of Silver City; Elliott Barker, a Sapello rancher-hunter houndsman-forest ranger who paid his dues in the sportsmen’s associations before becoming State Game Warden; and Aldo Leopold, then of the U.S. Forest Service and widely remembered here for laying the groundwork for the Gila Wilderness.

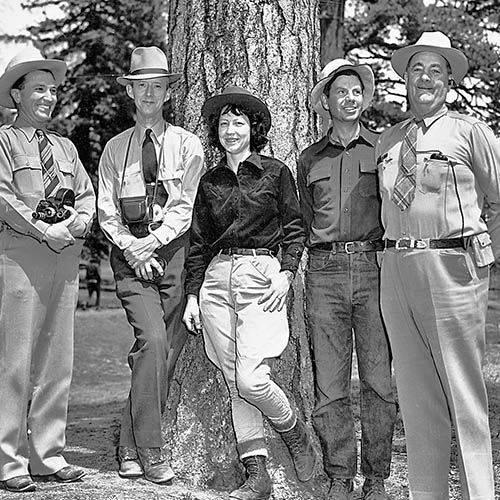

Photo: New Mexico State Records and Archvies.

Leopold’s work with the state’s sportsmen is less well known, but his voice was a catalyst as the associations grew to find their own voice and power. (Biographical information and quotes are from Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work, an excellent biography by Curt Meine).

An erudite leader and organizer

Aldo Leopold grew up in Burlington, Iowa, steeped in a conservation ethic. After earning a master’s degree from Yale Forest School, the enthusiastic greenhorn landed in the year-old Apache National Forest in southeastern Arizona in 1909. Two years later, favorably impressed forestry chiefs promoted Leopold to assistant supervisor of Carson National Forest in north-central New Mexico, and soon to supervisor.

It was on the Carson that he befriended Barker, who eventually succeeded him as supervisor there.

Severe illness forced Leopold out of the field. Fortunately for New Mexico’s budding conservation movement, the Forest Service placed him in its Albuquerque headquarters in 1915 as a specialist in recreation, fish and game, information and education.

The fit was excellent. Leopold was erudite, a leader and organizer, knowledgeable about wildlife and a passionate believer in its conservation. His appointment came at a critical time. Although New Mexico had a small Game and Fish Department and a State Game Warden who oversaw a field of unpaid deputies, the governor appointed the warden and the Legislature set all the seasons and bag limits. Legislators and governors jealously guarded their powers and resisted change. The system was imbedded in partisanship and rife with political payoffs – a situation hardly unique to New Mexico at the time.

It wasn’t all bad: Market hunting had been outlawed, a license fee system was in place, and closed seasons and bag limits imposed. A substantial force of unpaid deputy wardens at least sporadically enforced such game laws as existed, and a succession of state game wardens did try to educate the public about the need for conserving and restoring game populations. Still, progress was painfully slow, wrought through efforts by strong-minded individuals rather than organized groups.

That had changed dramatically just before Leopold’s appointment to the recreation slot, when the State Treasurer high-handedly but legally transferred money from the tiny Game Protection Fund, nearly wiping it out. Established in 1909 and fed a trickle of money, mostly from the sale of $1.00 hunting licenses, the fund was supposed to make the Game Department financially independent and was being carefully nurtured. The state game warden – backed by sportsmen – was saving up to build a trout hatchery.

Delivering the goods

Barker, in a history of the game protective associations he wrote in the early 1980s, said that act spurred sportsmen to action. “A group of far-sighted, public-minded sportsmen at Silver City realized that the wildlife situation would be no better under statehood than they had been before, unless an organized effort was made to improve them,” he wrote.

Led by Burford and Neblett, a group of Silver City hunters, anglers, ranchers and miners created the Sportsmen’s Association of Southwest New Mexico in 1914 – the state’s first organized sportsmen’s group, but hardly its last.

Leopold, as recreation officer, had free rein to travel, speak and organize. He had a key part in establishing the Albuquerque Game Protective Association and became its secretary. He joined Barker and others to form a similar group in Taos. He teamed with game biologist J. Stokley Ligon of the U. S. Bureau of Biological Survey to organize sportsmen in Magdalena, and launched another association in Santa Fe. Early in 1916, he rallied southern New Mexico sportsmen, traveling by rail and stagecoach with a first stop in Silver City. He and Burford discussed a statewide organization, and Leopold gave an evening talk to the 100-strong local association – a “Fine Lecture on Game Protection,” headlined the Silver City Independent.

He circled through southern New Mexico, proselytizing through the southern Rio Grande Valley to El Paso, then hit Alamogordo, Cloudcroft, Carlsbad and Roswell, where he drew 300 people. Soon, Barker writes, there were additional game protective associations in Socorro, Hot Springs (now Truth or Consequences), Deming, Las Cruces, Las Vegas, Raton, Chama and Tucumcari.

Leopold gave himself a pat on the back, in a letter to his mother: “The curious thing is that this thing has been tried time and again right here in New Mexico, and as promptly failed. I therefore can simply state that my plans and methods are delivering the goods.”

Certainly, the state was ripe for what he had to offer. Stubbornly resisting transfer to Washington, D.C., Leopold was determined to midwife a statewide organization. The first meeting was set for March 10-11, 1916 in Albuquerque.

Leopold was sure he had to be there, as he wrote to his supervisor, Arthur Ringland:

“The fact is that I have stirred up plenty of force and energy, but it has needed constant ‘steering.’ … If I am not there, there will be a squabble or somebody will run off hog-wild on some entirely impracticable proposition, and the whole movement will be ‘queered.’ I say this not from theory, but experience.”

Paper game laws

That first assembly stayed focused and created the New Mexico Game Protective Association (NMGPA), forerunner to the later Wildlife Conservation Association (organized in 1952) and the present New Mexico Wildlife Federation (1972). It elected Burford as president and Leopold as secretary, a position from which he wrote The Pine Cone, the group’s quarterly newsletter, and a series of press releases.

The organization debated a set of resolutions, setting a pattern its successors still use. In those early rounds, there was little debate: these men wanted action. They particularly supported better law enforcement, predator control and game refuges. They believed the agency should be financially independent, and they wanted a qualified, apolitical game warden to lead it. Eventually, they wanted a state game commission – a responsive and responsible citizens’ body appointed by the governor – to have authority to appoint the warden and to set hunting and fishing rules.

The warden’s position symbolized the goals, and hot battles marked the warden wars – who was appointed and who did the appointing.

Leopold, in the Sportsman’s Review magazine, stormed:

“Why is the big game of the West disappearing today? Principally for the reason that the game laws are not enforced. And why are they not enforced? Politics. Paper game laws and political game wardens are inseparable.”

Leopold pounded the theme in a press release right before the 1916 elections. “We need a super-Game Warden, a man fired with intense personal enthusiasm for the cause of game protection … (H)e should be responsible to neither political party, because there are no political issues involved in game protection.” He coined the term “efficiency game warden” and pressed it into the electoral rhetoric.

While aiming to free the agency from election-day politics, the association waded into the election, representing a thousand people, many of them prominent, wealthy and politically connected. That commanded attention from would-be governors, and both candidates pledged to work with the association in choosing a new game warden. The winner was Ezequiel C de Baca, a Democrat who apparently had Elliott S. Barker in mind.

C de Baca telegrammed association president Burford:

” … Many names have been suggested for the appointment, but none so far can measure up to the standard. To my mind there is one man, whose name has been scarcely mentioned as a possible appointee, who stands far above the others. This is Elliott S. Barker, of Taos.”

Barker later wrote, “I have always believed that Aldo Leopold wrote that telegram for the Governor.”

Political bifocals

But C de Baca died early in 1917 before taking office or appointing a warden. Lt. Governor Washington E. Lindsey, a Republican who had made no promises to the association, took office and picked Theodore Rouault Jr. of Las Cruces. Meine’s biography of Leopold presents Rouault as an alternative association candidate and chalked the appointment up as a success. Barker, though, opined that Lindsey and Rouault “saw things through political bifocals.” His recollection was that Rouault backed legislation to centralize regulatory authority in the governor’s and warden’s hands, and opposed the association’s idea of placing it in the hands of a state game commission.

“He did revise and greatly improve the Game Department accounting system and office procedures generally,” Barker conceded. “The GPA had seen the need for that and encouraged him.”

Since gubernatorial races came around every two years, the association soon geared up for Round Two. Burford, remembered by Leopold as New Mexico’s Father of Conservation, had died unexpectedly in 1917. The state association elected Neblett, by then a federal judge, to replace him, and Leopold continued to write and speak passionately on behalf of organizational goals. However Barker felt about Warden Rouault, Leopold and the NMPGA lobbied Governor-elect Octavio Larrazolo to keep him.

The Pine Cone editorialized, “The stockmen are never saddled with a sanitary board unsatisfactory to them. Likewise, the organized sportsmen should not be saddled with a Game Warden whom they do not approve.”

Photo: NMDGF.

Larrazolo ignored the flood of resolutions, telegrams, letters and endorsements. Angered, perhaps bewildered, that he could bypass such a potent group, the association formed a committee of 40 to confront him. With Leopold as lead spokesman and Barker as his second, the 40 crowded into Larrazolo’s office, standing room only. Barker later recounted that the governor quietly doodled while Leopold politely, logically and persuasively laid out the association’s case, taking a full hour.

The governor, Barker wrote, “reared back in h1s chair and said, ‘Gentlemen, when I was elected governor, I asked for no additional prerogatives. By the same token, I shall surrender none! Good day!'”

As Barker recounted it, “Leopold bristled up and said, ‘Governor Larrazolo, you have just announced that you cannot be elected to a second term as governor. Thanks for the appointment. Good day.”

100% Game Warden

Larrazolo appointed Thomas Gable, a politically connected man who had previously been territorial game warden and had strong ties to big ranching interests. Gable, according to Barker, opposed the commission system and also pushed legislation to place regulatory authority in the warden’s position – a practice in some other states, strongly opposed by New Mexico sportsmen.

Barker and others of his time adopted the commission system as such an obvious choice they wasted little ink explaining why, but Rollin Sparrowe, current president of the Wildlife Management Institute, accounts for the pioneers’ preferences.

“Having a governor-appointed individual determining the laws led to too many really personal and individual applications of opinions: Sparrowe said. “A broader commission represents the broader citizenry, and is thought to do a better job of giving the governor the kind of advice he needs.”

Gable made no headway in what sportsmen saw as a power grab, but Leopold tried to make good on his challenge to the governor.

Boldly, he asked legislators to sign a pledge not to vote for Larrazolo’s re-nomination and urged sportsmen to make a similar pledge as the I 920 campaign approached.

“When the sportsmen of New Mexico have mobilized and used their votes-then, and not sooner, will they obtain a 100-percent Game Warden: he wrote in The Pine Cone.

Regulatory reins

Whatever its differences with Larrazolo – who became a U.S. Senator-the association made a mark in the 1919 session. Resident trout fishermen were not required to have a license, although trout were virtually the only fish available. Sportsmen pushed for, and got, a resident trout fishing license-a major step toward the agency’s financial independence that generated $4.000 its first year, significant money at the time. Another financial boost: resident big game licenses went from $1.00 to $1.50. Legislation to create a game commission, however, failed.

The group realized that immersing itself in political campaigns to elect a friendly governor was not working. It altered tactics.

The association revitalized its efforts to create a game commission with hiring and regulatory authority, drafting legislation they presented in a July, 1920 meeting with key legislators. They laid groundwork for the upcoming 1921 session, but steered clear of partisanship during the gubernatorial campaign. Newly elected Gov. Merritt Mechem pledged to support the reorganization plan-with the proviso that the governor would retain hiring authority over the warden, a disappointment.

The bill passed, but another disappointment sneaked into it. “Wildlife legislation sponsors had not yet learned to ride herd after they have received legislative committee approval,· Barker lamented. The original bill gave the commission authority to “make such rules and regulations and establish such services as they may deem necessary.” But the midnight ambush prohibited the commission from changing any season or bag limit set by the legislature, except in cases of forest fire emergencies or to prevent undue depletion of game or fish.

The Legislature still held the regulatory reins.

The association, did, however, hit a homerun. The Game Protection Fund was protected from diversion:

“This act shall be guaranty to the person who pays for hunting and fishing licenses and permits that the money in said fund shall not be used for any other purpose than as provided in this act.”

The legislature also appropriated $15,000 from the general fund toward a trout hatchery, with the promise of another $15,000 the following year – Lisboa Springs Hatchery near Pecos, came about as a result.

A “he-man’s” job

The commission got right to work doing what it could. The hatchery project was launched almost immediately, and the commissioners, with input from the state and local associations, U.S. Forest Service rangers, ranchers and others, created a network of 26 refuges covering more than a half-million acres over the next two years.

Carrying a firearm into a refuge was illegal, which prevented poaching and aided enforcement. Protecting game animals from hunting allowed their populations to recover and, the theory went. to repopulate surrounding areas. Refuges continued as a cornerstone of game management for several decades; the numbers and acreage would markedly expand.

The association also found immediate sympathy with its stance on predator control. In keeping with the times, the membership-including Leopold-equated fewer predators with more game, and eradication of wolves and mountain lions as yielding a paradise of plenty. Although Leopold’s position dramatically evolved, many others’ did not.

Predator control also remained a cornerstone of management in New Mexico and the West for years to come.

The battle over governors and wardens was going less to the association’s liking, and peaked with Gov. James Hinkle’s unabashedly partisan appointment of Grace Melaven as warden in 1923. Wife of a Santa Rosa banker and Hinkle supporter, she had campaigned hard for the incoming governor. This was her reward.

“The reaction of the GPA and other sportsmen was generally violent,” Barker recalled. “She was neither a hunter nor a fisherwoman, was not a member of the GPA and had never taken any part in wildlife conservation.”

At an emergency meeting of the GPA, Barker wrote, “Some hot heads wanted to get rough and cause her all the trouble possible. Judge Colin Neblett stunned the group when he almost shouted, ‘Hold your horses. Can’t you see that the governor’s action is the best thing that ever happened for us?'”

Some booed. Barker recounted, but Neblett’s political acumen prevailed. Although treating the lady with respect, GPA members lobbied their legislators hard with Neblett’s premise “that the game warden is a HE-MAN’s job,” and that the only way to assure it was to let the commission do the hiring.

While they lobbied legislators, the Forest Service lobbied Leopold, persuading him to take a job as assistant director of the Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wis. He left New Mexico in the summer of 1924. His impressive legacy here included both wildlife conservation and the Gila Wilderness. In turn, these last wild lands had shaped and taught Leopold, renowned as the father of scientific game management and the thinker whose writings still shape conservation and land use ethics.

Even without his eloquent leadership, GPA members successfully pressed their case. The 1925 Legislature passed a bill placing hiring authority in the commission’s hands. The sportsmen had won.

Or had they?

The new governor, Arthur Hannett, wouldn’t sign the bill.

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations