New Mexico Wildlife (Spring 2003, Vol 48 Num 1)

Making tracks: a century of wildlife management, part 2 of 9

Sportsmen’s innovative self-tax funds wildlife restoration

By John Crenshaw

Former Public Affairs chief, New Mexico Wildlife editor, and game warden, retired in 1997.

New Mexico’s first territorial game warden was appointed in 1903. There was no school of wildlife management, no state fish hatchery system and few, if any, Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep and elk.

The Department of Game and Fish has grown out of that first appointment to an agency authorized to employ 286.5 individuals. Their mission is to provide the people of New Mexico with a flexible system of fish and wildlife management that perpetuates the state’s vast wealth of wildlife species.

During the last century of challenge, the agency has restored elk – too well in some minds; put Bighorn sheep back on the mountains; constructed and reconstructed six fish hatcheries with a seventh in the works. Along the trail the Department has assumed new responsibilities as the public’s desire to retain its wildlife heritage embraced species once believed less than desirable.

With this 9-part series “A Century of Wildlife Management” from New Mexico Wildlife, we look at the tracks this outfit made during its first century. Those tracks lead to the highest peak, and to the hottest desert, anywhere wildlife might need a helping hand.

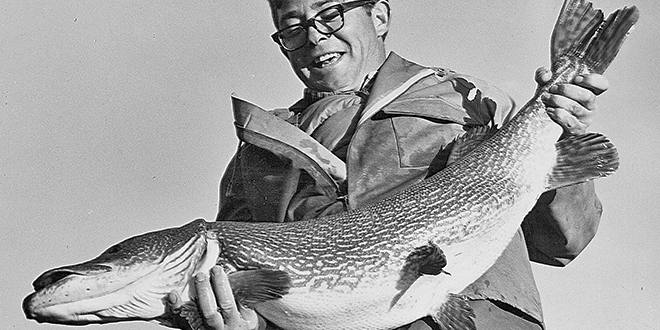

Above: Bob Patterson lands a Miami lake northern. Photo by John G. Whitcomb

Sportsmen’s innovative self-tax funds wildlife restoration

With the exception of requiring state licenses to hunt or fish in New Mexico, the Federal Aid to Fish and Wildlife Restoration programs may be the most important pieces of legislation in the history of fish and wildlife management in New Mexico.

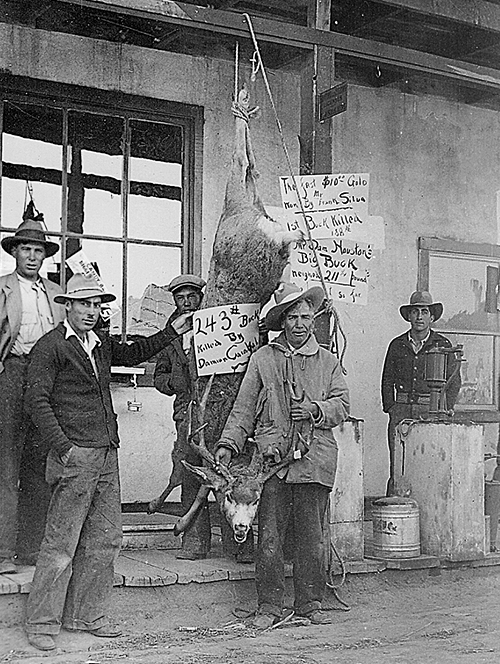

Photo: NMDGF.

The money generated by first the Wildlife Restoration Act of 1937, also known as the Pittman-Robertson Act so named for its congressional sponsors, provided the state a source of funding for the purchase and construction of many public recreation areas. Without this source of money, it’s doubtful New Mexico would have purchased the Colin Neblett Wildlife Area that encompasses Cimarron Canyon State Park, or the duck marsh in the Jemez Mountains that today is Fenton Lake State Park.

When combined with the money generated by the Sport Fish Restoration Act, also known as the Dingell-Johnson Act of 1950, New Mexico has benefited from $157.5 million in federal aid that helped transplant antelope, elk, bighorn sheep and turkeys and study black bears and cougars. The Department also has used it to create lakes, boat ramps, restrooms and courtesy docks at our state waters; build hatcheries and introduce popular sport fish like kokanee salmon and walleye.

Without this constant source of funding – tax money provided solely by those recreationists who purchase guns, ammo, archery equipment, fishing tackle, boats and fuel for motors – there more than likely would be far fewer boat ramps at state lakes, no trout fishing at Tingley Beach, no Quemado or Hopewell lakes.

Dollars and sense

Whether you venture to these places solely to watch the wildlife, or you seek elk steaks or rainbow trout for your frying pan, your life has been improved by the Federal Aid to Fish and Wildlife Restoration programs.

Nationally, these two acts have generated $4.1 billion for wildlife restoration and $3.4 billion for fisheries management. New Mexico has received $86.5 million on the wildlife side and $71 million for fisheries and boating. In fiscal year 2002 alone, the state received $5.3 million for fisheries work and $3. 7 4 million for wildlife projects. Only the sales of licenses, tags and stamps provide more money for the Department’s annual budget, with $11 million for hunting and $4 million for fishing during the fiscal year ending June 30, 2002.

The thought of the agency flailing away without the federal aid money challenges the imagination.

“Ohhh, wow, a disaster,” mulls Bob Patterson, a retired Department biologist who once coordinated the programs for the agency.

Most states would be in a dire situation. Game departments would be much smaller – probably not much more than police agencies – with a few fish and wildlife transplants. There certainly wouldn’t have been as much research done nor habitat and recreation areas acquired.

“Whoever pulled it off, it was such a good idea,” says Patterson. “A self-imposed tax on fishermen and hunters.”

A call to action

Sportsmen-conservationists, called together in 1936 by President Franklin Roosevelt to the North American Wildlife Congress, earn the credit. Appalled at the loss of wildlife in the previous half-century, they determined to reverse it.

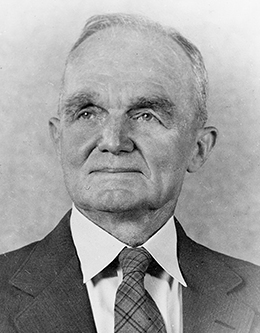

“Response to the President’s call was excellent,” wrote former New Mexico State Game Warden Elliott Barker, an organizing committee member and one of 1,500 delegates from the United States, Canada and Mexico. “From the outset it was apparent that the delegates had come for business and meant to get results.”

In his remarks to the group, which became the four-million-member National Wildlife Federation, Barker warned that passionate speeches and grandiose resolutions on behalf of wildlife often failed to translate into meaningful work.

“If we do not operate on the basis of actually getting action instead of more words and resolutions, then all or our efforts will have been in vain,” he recalled in his book, Ramblings in the Field of Conservation.

They got action in the form of support for and passage of the Pittman-Robertson Act.

“…a remarkable thing happened,” according to a history by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which administers the funds and monitors their use. “Organized sportsmen and the firearms and ammunition industries joined efforts with State wildlife agencies to meet the crisis with an ingenious long-range plan. At their urging, Congress extended the life of an existing 10 percent tax on ammunition and firearms used for sport hunting, but this time it earmarked the proceeds to be distributed to the States for wildlife restoration. Not just restocking. which had met with mediocre success at best, but other needed support systems as well – scientific research and habitat management to give animals a solid chance to re-establish healthy populations.”

Land mass and license sales

Led by Jay “Ding” Darling, a Pulitzer prize-winning editorial cartoonist, the federation championed the Pittman-Robertson act as a systematic, dependable funding source for wildlife restoration. President Roosevelt signed the landmark legislation in 1937. In 1950, President Harry Truman signed the Dingell-Johnson act to help states’ sport fishing projects via taxes on angling equipment.

The initial excise tax on firearms and ammunition set the pattern for both acts and their subsequent amendments: the tax is added on to firearms, ammunition, archery tackle, angling equipment and motorboat fuels at the manufacturing level. The cost passes through to the consumer.

The funding formula apportions money based on each state’s land mass (New Mexico does well there) and numbers of hunting and fishing licenses it sells (sparsely populated New Mexico does less well) with maximum and minimums; large, populous states such as Texas cannot shut out Rhode Island. States provide a 25 percent match – usually from hunting and fishing license revenues, sometimes from grants, special appropriations. or in-kind services – and spend the money up front, to be reimbursed by the federal government as projects move toward completion.

When the hunter of 1938 treated himself to a new 12-gauge, he helped pay for quail trapping and restocking or any of the dozens of projects soon to be funded by the new Pittman-Robertson Act.

Pronghorn and prairie chickens

The earliest apportionment in New Mexico was $20,000 that immediately went to work on research, habitat acquisitions and game stocking projects. Some failed, such as attempts to restock sage hens that had vanished from their former ranges. Some fit the mediocre success category: pheasants survived and established small populations. but New Mexico’s limited amount of cultivated land will never allow a Nebraska-like pheasant population.

Many, like pronghorn antelope trapping and transplanting, were uncontested successes.

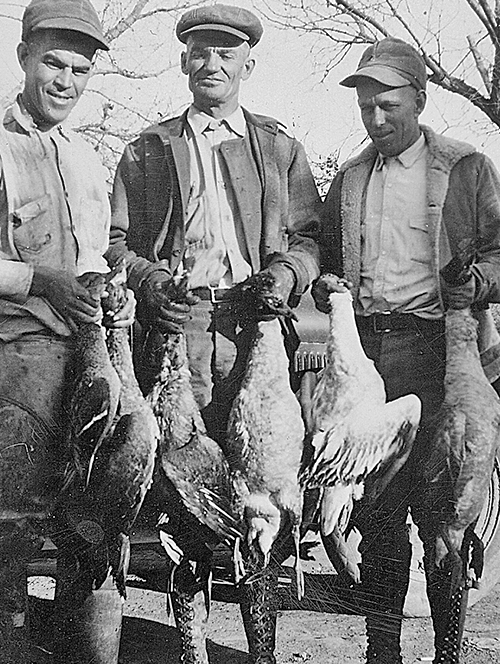

New Mexico had experience with antelope. It had already pioneered techniques for catching North America’s fastest land mammal for restocking prairie pastures. Funding from the Pittman-Robertson act gave a quick boost to the antelope work. During the next 65 years, Pittman-Robertson monies helped fund dozens of wildlife transplants – quail and turkey, some non-native birds like chukar, which didn’t take, and non-native big game like oryx and Persian ibex, which did. Considerable focus, though, was always on native antelope, elk. and wild sheep. The high-profile moves of Rocky Mountain bighorns into the Latir Peaks, and desert sheep restoration in the San Andres Mountains are two recent dramatic examples.

For the birds

Barker immediately started buying and protecting land for wildlife, a project his successors point to as probably the most critical in the long term.

“Going ‘way back. some of the most significant projects were land acquisitions,” said Bill Huey, who started with the Department in the 1940s as a conservation officer and eventually was its director. “All the prairie chicken area purchases around Milnesand and Floyd come to mind, and the Ladd Gordon waterfowl complex on the Rio Grande – farms and wetlands at La Joya, Belen and Bernardo. And of course, the Cimarron Canyon area. Those really made a lasting difference.”

Early acquisitions were for the birds: waterfowl and prairie chickens. The Department first used Pittman-Robertson funds to buy a stretch of river bottom along Cebolla Creek in the Jemez Mountains in 1940 as a waterfowl resting and feeding area. It dammed the creek in 1942 to form Fenton Lake.

Along the Pecos, the agency acquired what is now the Huey Waterfowl Area, and more recently the very substantial Brantley Waterfowl Area. On the Rio Grande, the agency had acquired a few small tracts of marsh north of Socorro in the 1920s, but the area was tiny and undeveloped. Wildlife restoration funds helped create something meaningful.

“The New Mexico Game Department went ahead and acquired and developed La Joya Marshes and made of it a very fine waterfowl area,” Barker wrote in Ramblings.

“Acquisition of some 30 small tracts was a difficult, tedious job but we finally completed it.”

La Joya was first in a string of agency-acquired farms and wetlands to aid wintering waterfowl. cranes and shorebirds, in conjunction with the federally managed Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge. The others are at Casa Colorada, Belen and Bernardo. Some acquisitions called for ingenuity, Huey recalled.

“We’d been leasing the Bernardo area from the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District and had developed it, so really thought we should buy it outright,” he said. “We contacted the district’s attorney, who suggested a condemnation suit. We told him, ‘We don’t condemn land,’ but he warned that if we went to bid, other people could bid on it and beat us out. So he suggested the friendly condemnation and that’s what we did. We had to do some wheeling and dealing in those days. and be persistent.”

Wild and woody

Barker set a pattern of persistence in buying land for prairie-chickens. As soon as Pittman-Robertson money became available, he immediately began acquiring what is now some 20 patches totaling 23,000 acres.

“We felt that units of one to two sections (square miles) here and there over their habitat would be more beneficial in restoring and maintaining the prairie chicken population than a single very large area,” he wrote.

Setting a general precedent for subsequent purchases., the Department managed prairie-chicken areas specifically for wild creatures.

“Grazing was eliminated and the native grasses. herbs and the dwarf havaard (shinnery) oak gradually came back to provide a natural habitat again,” Barker wrote. The agency also planted sorghum and maize to supplement natural feed in some spots.

In big game areas. the agency encouraged native vegetation, reseeded with grasses, legumes and woody browse plants, built waterholes, opened up habitat with controlled burns when that was still a land management heresy, limited motor vehicle traffic, and phased out livestock grazing.

The first big-land buy was an 8-mile stretch of scenic Cimarron River Canyon bottom and the adjacent mountains and meadows between Eagle Nest and Ute Park, totaling 33,000 acres. Even at 1950’s bargain price of $10 an acre, Barker had to stretch for it.

“To acquire it we had to use all the Federal Aid to Wildlife funds available for a three-year period.” he wrote. “We finally worked out a deal whereby we bought a third of the tract each year for three years.”

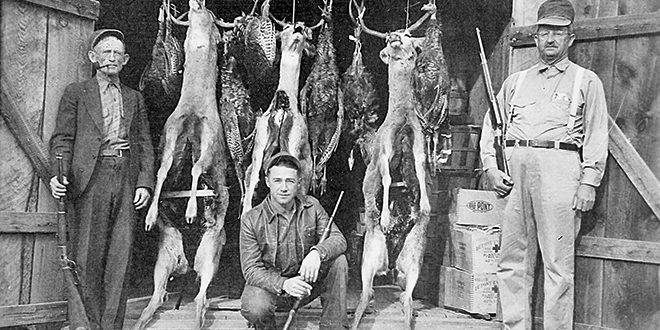

Below: Prairie-chicken areas were managed for all wild creatures. Photo by Martin Frentzel.

The agency developed modem facilities in the canyon bottom for picnickers. campers and anglers – the Cimarron is one of the best brown trout streams in the state – with Sport Fish and Wildlife Restoration funding both. Named the Colin Neblett Wildlife Area in memory of an outstanding commission chairman, it’s one of mny places those funding sources, combined with hunting and fishing license fee revenues, benefited both license buyers and the public in general.

Full speed ahead

Advent of the Dingell-Johnson Act really started things moving.

“Work which would not be possible otherwise to benefit fishing will be started at an early date .. .” Barker noted in his fiscal year 1951-52 annual report.

That first apportionment was small, $45,986.41, but Barker and the Department put it right to work. Soon, there were fishing lakes where none had been before. The agency was damming creeks, purchasing waterfront properties outright or leasing easements from private landowners, opening up numerous new opportunities for the public angler – and his friends and family, fishermen or not.

“I believe Hopewell Lake was the first, then there were others – Lake Roberts, for instance. Clayton Lake in the northeast was built with Pittman-Robertson and Dingell-Johnson both,” said Warren McNall, a retired fisheries biologist.

“The money itself was a lot for that era,” McNall said. “The development of habitat had to be the number one accomplishment, even though Lake Roberts has a short lifespan, as does Quemado and a few others, such as Snow Lake. That was tough, because they were small lakes that filled up rapidly.”

Hopewell, as the first Dingell-Johnson lake project, was a prototype. Under a special use permit from the U.S. Forest Service, the Department dammed a mountain meadow stream and created a new fishing lake in the San Juan Mountains. It also dammed other streams and improved existing dams, such as McGaffey Lake near Grants, and worked with irrigation districts and other lake owners to lease access for public fishing.

There are dozens of fishing waters Dingell-Johnson monies helped build or lease around the state, including some small ones – Morphy, San Gregorio, Maddox, Green Acres, Bear Canyon, Bill Evans, Pecos Monastery, Santa Rosa Power Dam – middle-sized ones such as Ramah, Storrie, Springer and Bonito – and some big ones, too.

“Ute Lake is one most people don’t think of that the Department put a lot of D-J money into,” said McNall.

The Department bought a 50,000-acre-foot recreational pool to assure the fisheries there – irrigators don’t annually suck it down for irrigation – and in 1984 covered the cost of dam improvements that basically doubled the lake’s size.

Stream access always has been important, too. “Land acquisition, for the benefit of fishing, included portions of the costs of the Rio de Los Pinos Fish and Wildlife Area and also a portion of the expenditures to date on the Rio Chama Fish and Wildlife Area, both of which are combination Fish and Wildlife projects,” Barker’s successor, Homer Pickens, wrote proudly in his 1953-54 annual report. “They open several miles of streams to public fishing.”

“Absolutely one of the best early ones was the one-and-a-half miles of San Juan River below Navajo Dam,” McNall said.

That happened in 1966. Since then, the agency acquired the Retherford and Hammond easements for anglers on the San Juan – an internationally renowned trout water.

More recent finds include access to stretches of the Rio Costilla, Coyote Creek and the Dry Cimarron, which McNall helped negotiate. Nor are all projects rural: Tingley Beach in metro Albuquerque now receives Dingell-Johnson funds.

Affordable science

The two acts also had a less visible effect: They made scientific game and fish management affordable.

The agency had hired pioneering biologist J. Stokley Ligon to assess the status of New Mexico’s wildlife in the 1920s, and few biologists trained in the nascent science of wildlife management were on board prior to passage of the Pittman-Robertson Act.

Funding was key; by the mid-50s, with P-R projects well under way and D-J money in the pipe, the agency boasted a baker’s dozen biologists delving into fish and wildlife habitats throughout the state.

Among the first investigations was an attempt to identify reasons hunters weren’t taking as much game as expected in the Gila area, which soon expanded into statewide game surveys. Another looked into the incidence and effects of quail malaria. A hands-on project built dozens of water catchments and self-feeding stations to supplement a natural food supplies for quail and dove.

Artificial feeding stations have long been abandoned. The quail malaria studies shaped future trap and transplant operations, however, preventing spread of the disease.

Huey, who conducted sandhill crane research early in his career, reviewed overall results.

“For the most part, we got some damned good information by using Pittman-Robertson money to finance research projects,” he recalled. “For some, the only benefit was a negative result, but about as many you consider the results positive. The beaver research project guided our trapping and transplanting of beaver. With the waterfowl project, we satisfied ourselves we didn’t have significant waterfowl production in the state, so we found ways to manipulate seasons and so on to increase hunter opportunity. One of the early and ongoing projects was the hunter harvest surveys of big game, waterfowl and upland game. We got solid information.”

“Using federal money to manage fisheries. Doing basic surveys, is probably one of the greatest things they did with the initial money,” said McCall. “It gave an inventory of what we had.”

On-the-job training

The Department sent newly hired fisheries biologists to inventory the status of native trout in the Pecos Wilderness and to assess fisheries in the Gila, Mimbres, Cimarron and Canadian drainages as soon as money was available. Investigations into other fish habitats soon followed, along with scientific research into growth rates and return rates on stocked fish, and investigations into hatchery diseases.

The fisheries biologists also developed onstream, in-person fishermen surveys, bolstered by extensive mail surveys, to measure anglers’ success rates, rates of use on various waters, and other data to manage the fisheries.

A 10-year, in-depth study into mountain lion life histories in the San Andres Mountains, completed in the mid- 1990s, gained international recognition as monumental research. A more recent in-depth study of black bears approaches the same status. Fisheries biologists used federal aid money to detect and fight whirling disease in trout, and to renovate our hatcheries to prevent its spread.

Through it all, an unintended, subtle but very valuable effect emerged from all the research projects: on-the-job training for emergent wildlife and fisheries biologists.

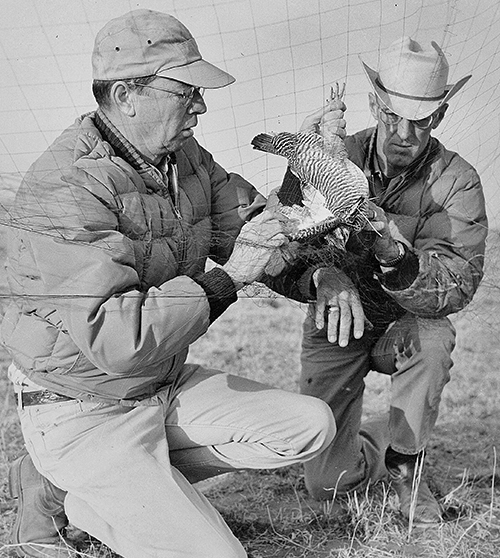

Bob Patterson started as a contract biologist. a graduate student sampling fish life and water quality on Elephant Butte Lake.

“I got trained as a fisheries biologist, and a lot of other guys who went to work for Game and Fish got trained the same way, in fisheries or big game or birds,” he said. “There wasn’t a specific program called ‘training,’ but I got into the project, did it, and they hired me right off the project. And they did others that way. I’ve never seen in print that it was a training ground for biologists, but come to think of it, it probably was. It’s meant a lot to the state. in a lot of ways.”

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations