Hiding inside small pet carriers in the back of a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service truck, eight very rare animals that once thrived in New Mexico waited to go home.

It was a sunny, late September afternoon when wildlife biologists, conservationists, ranchers and local residents gathered on the side of a dirt road at the Moore Land and Cattle Company ranch east of Wagon Mound for the rare opportunity to witness the reintroduction of the black-footed ferret to New Mexico. The ferrets were driven down from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s National Black-Footed Ferret Conservation Center near Fort Collins, Colo. where the animals are raised in captivity and prepared for release at sites throughout the interior western United States.

The release location was only the third ever in the state; several years have passed since the last reintroduction attempt at the Vermejo Park Ranch in 2012 in Colfax County, not too far away from this 500-acre black-tailed prairie dog town.

“Is the prairie dog the villain or is it just getting used by a lot of other species, and then the prairie dog gets the blame?” asked Moore, who has owned the ranch since 1971. “Maybe the little ferrets could make them move around so they don’t sit in one spot.”

Black-footed ferrets were believed to be extinct in the early 1980s. The species has been listed as endangered across its entire range since 1967, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service. In 1981, and to the surprise of many ferret researchers, one last colony was found in northwestern Wyoming, said Pete Gober, black-footed ferret recovery coordinator with the Service. “It did ok for a few years but it was impacted by plague,” he explained. “What few animals were left there had to be pulled into captivity.” Those captured survivors provided the breeding stock for all black-footed ferrets that are alive today.

The ferrets existed in New Mexico up until the mid-20th century, said Jim Stuart, endangered nongame mammal biologist with the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish.

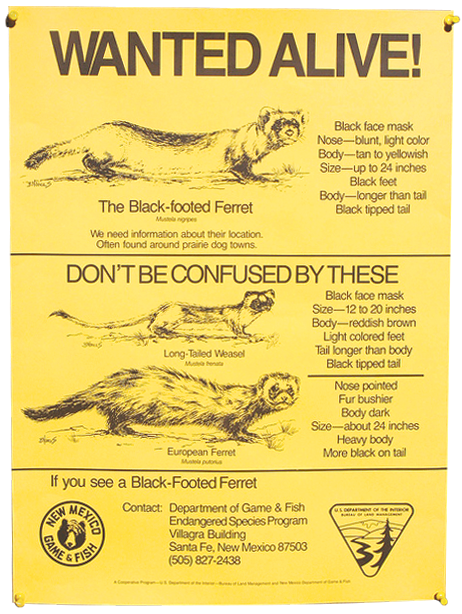

After the discovery of ferrets in Wyoming, there was a big push to try to identify if there were any ferrets left in New Mexico as well as in other states where it historically occurred, Stuart said. “There was a lot of public outreach and requests for information from the public, a lot of surveys were done on prairie dog towns throughout New Mexico, and none of them ever detected a ferret,” he said. “After about a decade or so of surveys, we assumed the species was indeed gone from New Mexico.”

In the wild, black-footed ferrets reside in prairie dog towns. For ranchers such as Greg Moore, owner of the 25,000-acre ranch, this program is an opportunity to restore native species to his property.

And the large prairie dog population on Moore’s ranch means ferrets can thrive there. Black-footed ferrets rely almost exclusively on prairie dogs, for food and for their burrows, which provide denning and shelter sites; the presence of a predator species would keep the prairie dog population in check, enable ranchers to avoid shooting or poisoning the animals and possibly force them to move elsewhere before they further damage the land damage the land by creating too many burrows.

The two other releases conducted in New Mexico at Vermejo Park happened in 2008 and 2012; today, it’s unknown if any have survived due to drought and plague. At present, the release program at Vermejo is on hold.Gober estimates that there are probably 300 to 400 ferrets in the wild across the former range which included portions of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountain states. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has released ferrets in 30 different places on prairie dog towns—on public, tribal and private lands—across the west. Ten sites have not succeeded due to plague, he noted.

Moving forward, wildlife biologists will focus on keeping the plague—referred to as the sylvatic plague in animals and the bubonic plague in humans when it is transferred to people via flea bites, direct contact with infected animals and bites from infected mammals—at bay. Both prairie dogs and black-footed ferrets are susceptible to plague, which occurs throughout New Mexico and was first detected in the state in the 1930s. Although the released ferrets were already vaccinated against the sylvatic plague, the prairie dogs at Moore’s ranch were not. In November 2018, department and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service personnel administered edible peanut-butter flavored baits that contained sylvatic plague vaccine on the prairie dog town in order to inoculate the rodents. Application of the vaccine baits will have to be done on an annual basis to ensure that a large percentage of the prairie dogs remain resistant to the disease in the event of an outbreak.

The goal is to conserve both species. “If we lose the prairie dogs, we lose the ferrets,” said Stuart. “Managing for ferrets requires a lot of work since disease is by far the biggest threat to survival of ferrets and prairie dogs alike. I see this [reintroduction] as a first few footsteps in terms of reintroducing this animal at many more places in New Mexico.”

One by one, each crate is held over a prairie dog burrow. The ferrets, four male and four female, hide inside a black corrugated pipe. Sometimes the animals just slide in first without hesitation. Sometimes they don’t and they take time to finally enter the prairie dog hole, Gober said.

Moore is invited to release the first ferret on his ranch.

It takes several minutes to coax the ferret out of the crate with a stick. The tube and ferret slide into the hole. Then the animal twists around to look up through the opposite end of the tube and chatter loudly in protest.

Upon release of the ferret, a chunk of prairie dog meat was tossed down the burrow so the newly introduced animal would not have to hunt on its first night in the wild. Other than that, the ferrets were on their own.

Each microchipped ferret will be monitored by wildlife biologists over the coming year. A total of eight release burrows were marked with orange flags. A few are released at one area, the rest further down the road at another area with a high density of prairie dogs. The ferrets are not expected to remain where they were released.

Moore noted that better habitat management could help keep four other species on his land—ferruginous hawk, swift fox, burrowing owl and mountain plover—off the endangered species list.

“Maybe we can stop that from happening if enough landowners will do what we’re doing here,” said Moore. “One hundred landowners would make a wonderful start.”

By reintroducing the endangered ferrets, Gober added, “you are able to conserve prairie dogs, and if you conserve enough prairie dogs in enough places you’ll help other species on the coattails of the ferrets.”

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations