New Mexico Wildlife (Winter 2002-03, Vol 47 Num 4)

Making tracks: a century of wildlife management, part 1 of 9

By John Crenshaw

Former Public Affairs chief, New Mexico Wildlife editor, and game warden, retired in 1997.

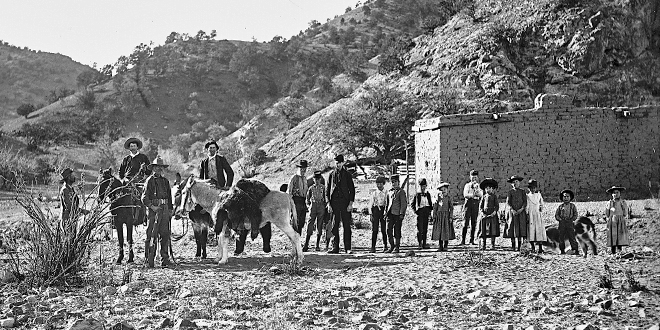

New Mexico’s first territorial game warden was appointed in 1903. There was no school of wildlife management, no state fish hatchery system and few, if any, Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep and elk.

The Department of Game and Fish has grown out of that first appointment to an agency authorized to employ 286.5 individuals. Their mission is to provide the people of New Mexico with a flexible system of fish and wildlife management that perpetuates the state’s vast wealth of wildlife species.

During the last century of challenge, the agency has restored elk – too well in some minds; put Bighorn sheep back on the mountains; constructed and reconstructed six fish hatcheries with a seventh in the works. Along the trail the Department has assumed new responsibilities as the public’s desire to retain its wildlife heritage embraced species once believed less than desirable.

With this issue of New Mexico Wildlife, we present the first in a series (“A Century of Wildlife Management” ) looking at the tracks this outfit made during its first century. Those tracks lead to the highest peak, and to the hottest desert, anywhere wildlife might need a helping hand.

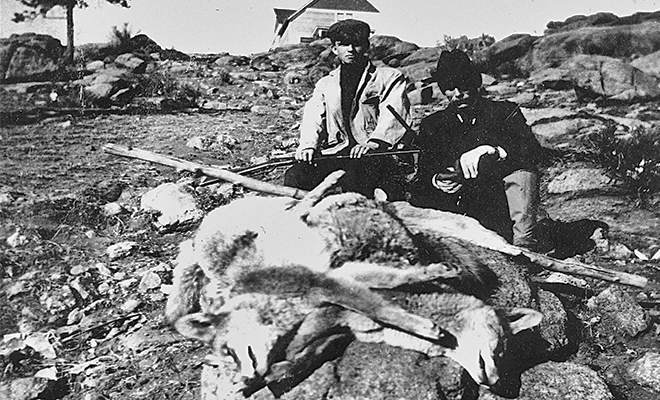

Above: Two young fishermen with bass, 1899. Photo: New Mexico Records and Archives

Making tracks: a century of wildlife management

New Mexicans of the 1860s were eye witnesses to a phenomenon of such huge scale it eventually trampled resistance to laws protecting wildlife: the buffalo’s plunge from a population of 40 million or more to only dozens in a few decades. Our bison, gone from New Mexico by the 1870s, were part of the huge southern herd, its fate recounted by William T. Hornaday in The Extinction of the American Bison:

“In Texas a miserable remnant of the great southern herd still remains in the ‘Panhandle country,’ between the two forks of the Canadian River … (It) seems quite certain that not over twenty-five individuals remain. These are so few, so remote, and so difficult to reach, it is to be hoped no one will consider them worth going after, and that they will be left to take care of themselves …”

He calculated the total U.S. population in 1889 at 85 head, the total North American population at 635. Fortunately, a few farsighted ranchers and Native Americans captured a few, bred them in captivity, and saved the species from extinction.

In addition to wanton slaughter, burgeoning populations of people were simply eating their way through the game herds. Natives and newcomers subsistence hunted year-round for their personal larders. Market hunters supplied railroad construction crews, restaurants and butcher shops; fresh buffalo hump or hindquarters of elk relieved soldiers’ tedious rations of hardtack and bad bacon. Miners and loggers fed on venison. At the same time, sharply increased herds of sheep and cattle in post-Civil War New Mexico competed with big game for food and spread devastating diseases.

Within a few decades after the New Mexico bison’s demise. Rocky Mountain bighorn also would be extinct in the territory. with elk soon to follow. Deer and pronghorn antelope populations were falling rapidly. With their most visible and valued wildlife disappearing, New Mexicans nurtured a new conservation conscience. By 1880, it took seed.

Too little, too late

“In 1880, New Mexico passed a protection law but by that time, the bison were already gone.” (The North American Bison, by Dave Arthun and Jerry Holechek. N.M. State University)

“No person shall kill, ensnare, trap, or in any manner take within this Territory, any elk, buffalo, deer, fawn, antelope, mountain sheep, wild turkey, grouse, or quail, between the first day of May and the first day of September in any year… The provisions of this act shall not be applicable to travelers or other persons who may be in camp, and whom necessity may compel to kill one or two animals for their subsistence.” (Chapter 25, as passed by the Territorial Assembly of New Mexico.)

The 1880 law’s passage, in hindsight, was tardy. It set no big game limits. It left many species unprotected. It did nothing about commerce in hides and meat. It did, however, set a closed season – a major first step – and its simple existence was remarkable. Some realities of the times, for instance, show up in the waiver of rules for travelers. No territorial legislator could consider telling a westering pioneer not to feed his family off the land, as in the story told by Elisha Leslie of Carrizozo in 1938.

“In the spring of 1883 my father decided to sell out his farm near Dublin Texas, and move to Lincoln County (N.M.). Each wagon had their own provisions and each family did their own cooking over a camp fire. The woman and children slept in the wagons and the men slept on the ground. Each wagon had their own chuck box and water kegs. The only fresh meat that we had on the trip were prairie chickens and antelope that we shot on the way…” (American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1940).

Her story was repeated time and again in the diaries of the soldiers, miners, homesteaders, cowboys, loggers, tanners, even the city dwellers, all part of New Mexico’s growing population. The 61,500 residents of 1850 grew to 195,300 by 1900 and 327,300 by 1910.

But legislators did tighten the rules. The statutes of 1895 set a three-month fall season on deer, elk and antelope. It set a six-month season on quail and wild turkey. It set no bag limits on big game or birds, but forbade “wanton” killing. A first stopper on market hunting, it banned killing animals for their hides. Though not banning sale of game meat, it gave a nod toward preventing waste by the sellers. In another couple of years, lawmakers would take on commercialization of wild game meat.

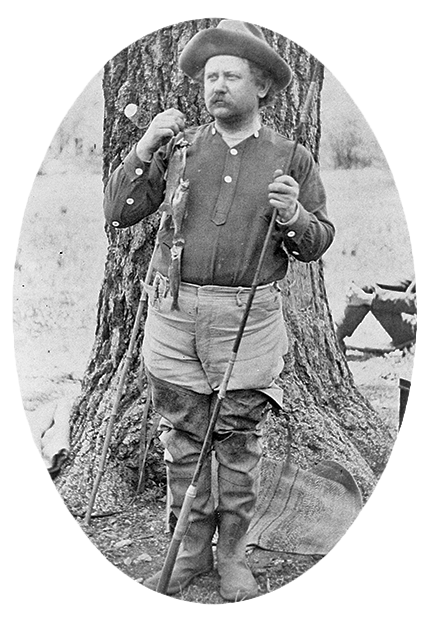

Market hunting

Comfortably removed by more than a century from the last of the market hunting, we can barely comprehend the depth of its history, its extent and impact. It began soon after Europeans arrived – shipping logs recorded some 600,000 deer hides sent from Savannah, Ga., to England between 1755 and 1773, for instance. By the 1870s, repeating rifles and railroads made hunting profitable for professionals and part-timers alike. Buffalo from the western prairies, elk and bighorn sheep from the Rockies, deer from Maine to Michigan were killed and shipped by tens of thousands, in tons, to insatiable city markets. Midwestern prairies and southern marshes were swept virtually clean of upland birds and waterfowl. Though eventually protected, even song birds robins, bobolinks, finches, juncos, waxwings were killed for the market and literally baked into pies.

In the West, the post-Civil War rush for land was on, and mining towns boomed – a timely boom for one Frank Mayer, a “buffalo runner” who had made a little money hunting for hides, but not the fortune he craved. After the buffalo were gone, Mayer landed in Leadville, Colo., and quickly saw that prospecting was not where he would make his fortune; he contracted with a wholesaler to deliver three tons of rough-dressed game meat a week. Though not replicated at quite this scale in New Mexico, Mayets mining town tale is instructive:

“I went into market hunting, and here I got hold of some of the dollars that eluded me in the buffalo business. The fact is that, hunting deer, antelope, elk, mountain sheep, and bear for the mining camp markets of Colorado, I earned more, in 1880, than during any two years on the buffalo ranges. And the work was three or four times as easy and pleasant. For one thing I got better prices for the meat I delivered to the camps than I ever got from buffalo,” he wrote in his memoirs, The Buffalo Harvest, with Charles B. Roth.

He received 10 cents a pound for deer, elk and antelope, 12 and a half per pound for bighorn sheep, and 15 cents a pound for bear. He killed 11 mule deer and four antelope his first day on the job, three bulls and four cow elk on the second. He killed and sold 35,000 pounds- 17 and a half tons – of game meat in his first three months, and he stayed in business for several years more .

His profession was legal, his skills respected. Many like him made a good living, a few became rich. Many tanners and ranchers throughout the country sold birds or big game for extra cash or traded for necessities – as an Otero Mesa rancher related of his predecessors: “They’d ride into El Paso, taking along a wagon, and load it with antelope they shot along the way. Then they’d trade the antelope for the provisions they needed, like canned goods, flour and beans.”

The ban

The Territorial laws of 1897 reflected a sea change in the view of wildlife as a commodity: They banned market hunting, prohibiting sale of game, birds or fish taken in New Mexico and forbade shipping them out of the territory by common carrier. Though not limiting how many deer, elk or antelope a person could take, they did limit the take to animals “with horn,” protecting females and young of the year.

When the territorial legislature met in 1899, it finally set a bag limit of one deer, antelope or elk with horns – then closed the season on elk. The protection, as it had been for buffalo and Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep, was too little, too late.

“The turn of the twentieth century saw the Merriam elk population in the United States so low that it could not be saved from extinction. Hunting and overgrazing by domestic livestock caused its extirpation between 1902 and 1906,” according to records collected for The Elk of North America, Ecology and Management, an exhaustive tome on the species.

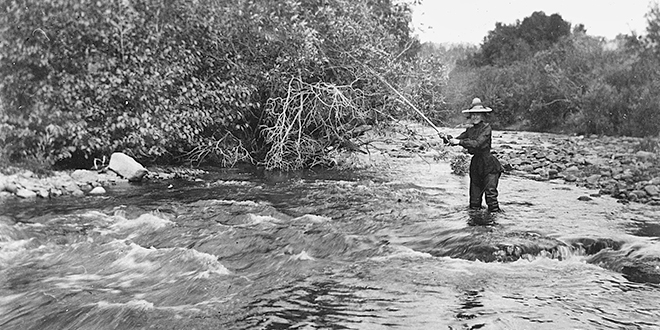

They set the first trout-fishing season, June 1 through Jan. 31. with a 6-inch minimum size limit (but no bag restrictions), and established hook and line as the only legal means of taking game fish. Revealing prohibitions included bans on using drugs, explosives, seines and nets, or diverting a stream to strand fish by the basketful.

The last Rocky Mountain elk in New Mexico went down about 1910. Whether it fell to a hungry homesteader or a hard winter, we don’t know. But venison fed our forebears, as in this hunt recounted in “The Life of Liven Serna, Famous Bear Hunter of the Rayado.”

“I stayed out looking for more deer. I finally saw a bunch of deer and I killed three of them …. I don’t know how many deer I have killed, because before deer were protected, I used to bring down as many as four at a time.”

Liven Serna cut back in keeping with the times. Others simply became more careful. “Calves were for selling. Deer were for eating,” was one simple explanation.

Who pays, how

The Legislature created what would become the game department in 1903 and put Page Otero in charge. The Legislature, however, still reserved authority to designate which species would be protected. It decided which predators to target with bounties. It opened and closed hunting and fishing seasons, set bag and size limits, established the methods of hunting and fishing. And Legislatures then and now have final say on the agency’s budget.

In the early 1900s, the budget came from the general fund and tax revenues, and the legislature of a sparsely populated and hardly prosperous territory was scarcely generous.

Nationally, hunting licenses and fishing licenses provided operating revenue for the new game and fish departments – a user pays system – and many New Mexicans wanted to follow suit. Chief among those was Territorial Game Warden William Griffin, who lobbied legislators for a license fee system and hit pay dirt in 1909.

Those 1909 statutes set the resident big game license fee (game quadrupeds and turkey) and bird license (quail, grouse, etc.) at a nice, round $1.00 each, and nonresident fees at $25. The statute created other licenses and permits to regulate storage and shipping. New Mexicans still did not have to buy a fishing license, but nonresidents were required to buy one for a dollar.

The law acknowledged wildlife’s value, creating civil penalties – imposed in addition to any criminal fines – for illegally taking a game animal or fish, to reimburse the state for its loss. Civil damages started at $50 for deer and ranged through $100 for antelope to $200 for elk and sheep. Civil assessments were $10 for a game bird and $1.00 for each illegally taken fish. Civil penalties now range from $5.00 for each fish to $1,000 for bighorn sheep, ibex and oryx.

Its key financial creation was the Game Protection Fund, into which all license fees would be paid, for disbursement with the Legislature’s approval. Other firsts: The Legislature appropriated $500 for operating expenses and funded an assistant’s position at $900 a year.

Photo: New Mexico Game and Fish

When 1912 and statehood rolled around, the Legislature created the Department of Game and Fish by name. It dictated that the governor would appoint as State Game Warden “some person skilled in matters relating to game and fish; although first State Game Warden Trinidad C de Baca acknowledged in his first report that he “was practically unacquainted with the work.” Nonetheless, it was a nominal step toward ensuring that wildlife professionals would operate the agency.

The 1912 Legislature also created the Class A Park and Lake licensing act. It exempted private-land ranches licensed under its provisions from all state game and fish laws and regulations and gave them ownership of the game within their boundaries – essentially treating big game like privately owned livestock. That created a system which, although amended and narrowed, reverberates still in New Mexico’s wildlife management and politics.

Financially self-sustaining

The legislature appropriated the warden’s salary money and some expenses from the general fund for a few more years, but license fee revenues were running at something more than $7,000 annually. Thus, a proud warden Thomas Gable reported at the end of 1911,

“…the revenue now derived from licenses issued by this office renders it self sustaining and no further appropriation will be needed from the legislature for the game and fish department.”

He acknowledged that if the agency built a fish hatchery, it would need some financial assistance.

Through assiduous savings and with an eye toward that fish hatchery, the agency built a substantial balance in the game protection fund – only to watch in astonishment when the state treasurer legally raided it in 1914.

It was a huge blow, but galvanized outraged sportsmen into action. The Game Protective Association, a statewide coalition of sportsmen’s groups inspired and led by notable conservationist Aldo Leopold. quickly garnered considerable clout and was bending legislator’s ears.

It took them several years to reach all their goals, but in the interim the 1915 Legislature did create a resident fishing license requirement – for warm-water species only, although virtually all fishing at the time was for trout. A trout-fishing license finally came in 1919 when resident big game license fees were boosted to $1.50.

The first commission

By then, the Game Protective Association was strong, and it wanted a citizen’s body – a State Game Commission – to set hunting and fishing regulations, hire the state game warden and set the department’s overall direction. They also demanded assurance that the license-fee monies they paid into the game protection fund went for wildlife management.

They protected the Game Protection Fund starting in 1921, receiving the statutory assurances they sought. “This act shall be guaranty to the person who pays for hunting and fishing licenses and permits that the money in said fund shall not be used for any other purpose than as provided in this act.”

“As provided” meant: “It is the purpose of this act to provide an adequate and flexible system for the protection of the game and fish of New Mexico, and for their use and development for public recreation and food supply.” Those wordings stand today.

The same 1921 Legislature created a three-member commission, but reserved the right to set seasons and bag limits; the governor continued to appoint the agency’s chief. Another section authorized the commission to “make such rules and regulations and establish such service as they may deem necessary to carry out all the provisions and purposes of this act,” but did not fully relinquish that authority for another decade.

Today a seven-member body appointed by the governor, the commission has since gained those responsibilities and more, but the system stands on the work of those 1920s conservationists. It was not until 1937 that the federal Wildlife Restoration Act was passed by Congress, funding wildlife restoration and protection through an 11 percent excise tax on sporting arms, ammunition and archery equipment.

The final foundations

When the Legislature delegated regulatory authority to the commission six years later, it finished a solid legal foundation that supports wildlife management to date. The newly strengthened commission in turn hired Elliott Barker, an avowedly independent conservationist, to head the agency. With the commission’s blessing and backing, he set a standard of professionalism that withstood the tests of time and politics.

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations

New Mexico Wildlife magazine Conserving New Mexico's Wildlife for Future Generations